(updated below - Update II)

Remember when, in the wake of the 9/11 attack, the Patriot Act was controversial, held up as the symbolic face of Bush/Cheney radicalism and widely lamented as a threat to core American liberties and restraints on federal surveillance and detention powers? Yet now, the Patriot Act is quietly renewed every four years by overwhelming majorities in both parties (despite substantial evidence of serious abuse), and almost nobody is bothered by it any longer. That's how extremist powers become normalized: they just become such a fixture in our political culture that we are trained to take them for granted, to view the warped as normal. Here are several examples from the last couple of days illustrating that same dynamic; none seems overwhelmingly significant on its own, but that's the point:

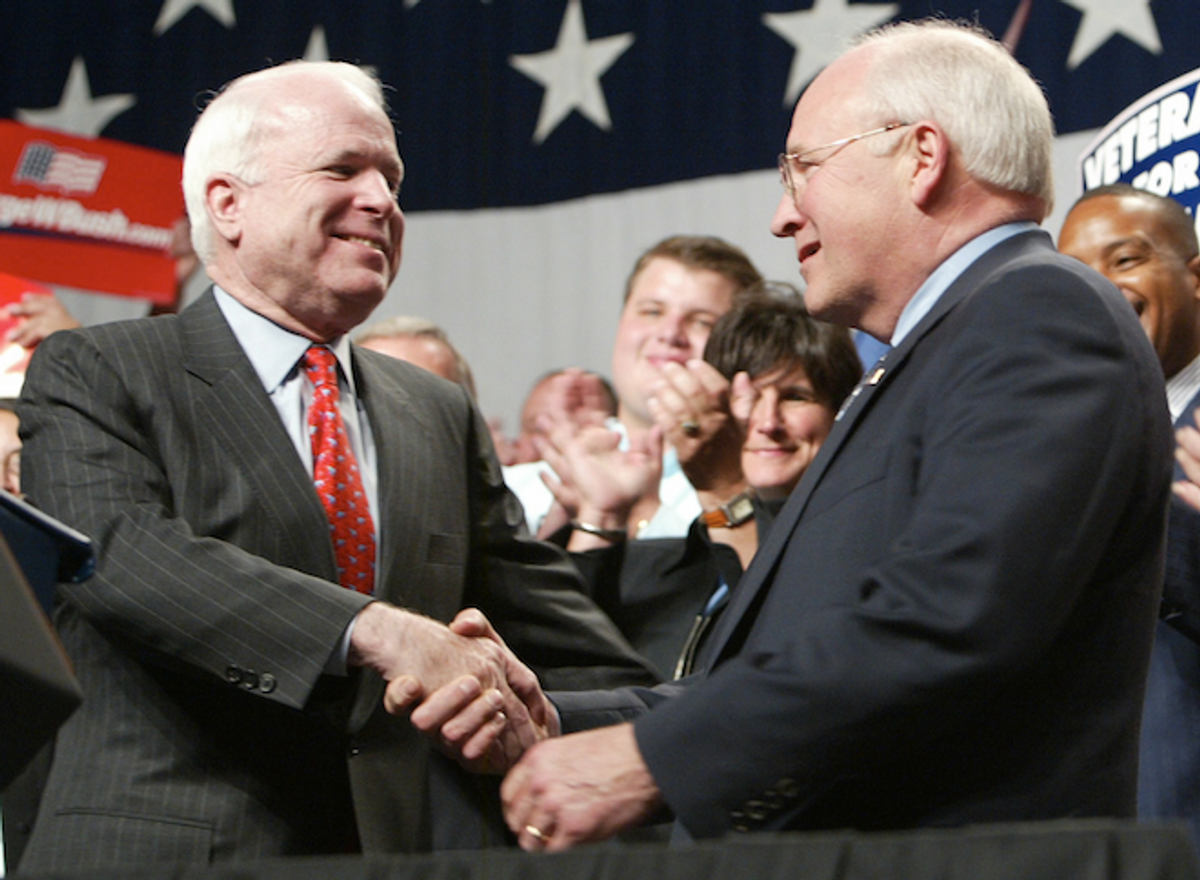

After Dick Cheney criticized John McCain this weekend for having chosen Sarah Palin as his running mate, this was McCain's retort:

Look, I respect the vice president. He and I had strong disagreements as to whether we should torture people or not. I don't think we should have.

Isn't it amazing that the first sentence there ("I respect the vice president") can precede the next one ("He and I had strong disagreements as to whether we should torture people or not") without any notice or controversy? I realize insincere expressions of respect are rote ritualism among American political elites, but still, McCain's statement amounts to this pronouncement: Dick Cheney authorized torture -- he is a torturer -- and I respect him. How can that be an acceptable sentiment to express? Of course, it's even more notable that political officials whom everyone knows authorized torture are walking around free, respected and prosperous, completely shielded from all criminal accountability. "Torture" has been permanently transformed from an unspeakable taboo into a garden-variety political controversy, where it shall long remain.

Equally remarkable is this Op-Ed from The Los Angeles Times over the weekend, condemning President Obama's kill lists and secret assassinations:

Allowing the president of the United States to act as judge, jury and executioner for suspected terrorists, including U.S. citizens, on the basis of secret evidence is impossible to reconcile with the Constitution's guarantee that a life will not be taken without due process of law.

Under the law, the government must obtain a court order if it seeks to target a U.S. citizen for electronic surveillance, yet there is no comparable judicial review of a decision to kill a citizen. No court is even able to review the general policies for such assassinations. . . .

But if the United States is going to continue down the troubling road of state-sponsored assassination, Congress should, at the very least, require that a court play some role, as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court does with the electronic surveillance of suspected foreign terrorists. Even minimal judicial oversight might make the president and his advisors think twice about whether an American citizen poses such an "imminent" danger that he must be executed without a trial.

Isn't it amazing that a newspaper editorial even has to say: you know, the President isn't really supposed to have the power to act as judge, jury and executioner and order American citizens assassinated with no transparency or due process? And isn't it even more amazing that the current President has actually seized and exercised this power with very little controversy? Recall that when The New York Times first confirmed Obama's targeting of citizens for assassinations in 2010, it noted, citing "officials," that "it is extremely rare, if not unprecedented, for an American to be approved for targeted killing." No longer. That presidential power -- literally the most tyrannical power a political leader can seize -- is also now a barely noticed fixture of our political culture.

Meanwhile, we have this, from the Associated Press yesterday:

Remember when John Poindexter's "Total Information Awareness" program -- which was "to use data mining technologies to sift through personal transactions in electronic data to find patterns and associations connected to terrorist threats and activities": basically create real-time surveillance of everyone -- was too extreme and menacing even for an America still at its peak of post-9/11 hysteria? Yet here we have the NYPD -- more than a decade removed from 9/11 -- announcing a very similar program in very similar terms, and it's almost impossible to envision any real controversy.

Similarly, in the AP's sentence above describing the supposed targets of this new NYPD surveillance program: what, exactly, is a "potential terrorist"? Isn't that an incredibly Orwellian term given that, by definition, it can include anyone and everyone? In practice, it will almost certainly mean: all Muslims, plus anyone who engages in any activism that opposes prevailing power factions. That's how the American Surveillance State is always used. Still, the undesirability of mass, "all-seeing," indiscriminate surveillance regime was a given -- a view, in sum, that the East German Stasi was a bad idea that we would not want to replicate on American soil -- yet now, there is almost no limit on the level of state surveillance we tolerate.

In The New York Times yesterday, Elisabeth Bumiller wrote about the very moving and burdensome plight of America's drone pilots who, sitting in front of a "computer console [] in the Syracuse suburbs," extinguish people's lives thousands of miles away by launching missiles at them. The bulk of the article is devoted to eliciting sympathy and admiration for these noble warriors, but when doing so, she unwittingly describes America's future with domestic surveillance drones:

Among the toughest psychological tasks is the close surveillance for aerial sniper missions, reminiscent of the East German Stasi officer absorbed by the people he spies on in the movie "The Lives of Others.” A drone pilot and his partner, a sensor operator who manipulates the aircraft’s camera, observe the habits of a militant as he plays with his children, talks to his wife and visits his neighbors. They then try to time their strike when, for example, his family is out at the market.

“They watch this guy do bad things and then his regular old life things,” said Col. Hernando Ortega, the chief of aerospace medicine for the Air Education Training Command, who helped conduct a study last year on the stresses on drone pilots. . . . "You see them wake up in the morning, do their work, go to sleep at night," said Dave, an Air Force major who flew drones from 2007 to 2009 at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada and now trains drone pilots at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

That's the level of detailed monitoring that drone surveillance enables. Numerous attributes of surveillance drones -- their ability to hover in the same place for long periods of time, their ability to remain stealthy, their increasingly cheap cost and tiny size -- enable surveillance of a breadth, duration and invasiveness unlike other types of surveillance instruments, such as police helicopters or satellites. Recall that one new type of drone already in use by the U.S. military in Afghanistan — the Gorgon Stare, named after the "mythical Greek creature whose unblinking eyes turned to stone those who beheld them" — is "able to scan an area the size of a small town" and "the most sophisticated robotics use artificial intelligence that [can] seek out and record certain kinds of suspicious activity"; boasted one U.S. General: “Gorgon Stare will be looking at a whole city, so there will be no way for the adversary to know what we’re looking at, and we can see everything."

There is zero question that this drone surveillance is coming to American soil. It already has spawned a vast industry that is quickly securing formal approval for the proliferation of these surveillance weapons. There's some growing though still marginal opposition among both the independent left and the more libertarian-leaning precincts on the right, but at the moment, that trans-ideological coalition is easily outgunned by the combination of drone industry lobbyists and Surveillance State fanatics. The idea of flying robots hovering over American soil monitoring what citizens do en masse is yet another one of those ideas that, in the very recent past, seemed too radical and dystopian to entertain, yet is on the road to being quickly mainstreamed. When that happens, it is no longer deemed radical to advocate such things; radicalism is evinced by opposition to them.

* * * * *

Whatever one thinks of the RT network, Alyona Minkovski, a host of a show on that network, is an excellent journalist and interviewer. Last night was her last show -- she's leaving to work on a Huffington Post video show -- and I was on last night, along with Jane Hamsher, discussing several domestic police state issues related to the topics discussed here:

* * * * *

Over the weekend, in the column I wrote hailing the Internet's capacity to detect falsehoods and myths better than traditional journalism, I made reference to the "mass panic" caused by Orson Wells' 1938 broadcast of "The War of the Worlds." Numerous people -- in comments, via email and elsewhere -- objected by arguing that no such panic was ever documented. Journalism Professor W. Joseph Campbell makes the case here that this is nothing more than urban myth. He suggests that the widespread propagation of this myth on the Internet undermines my argument because it shows how the Internet can spread rather than combat falsehoods (Dan Drezner makes a related argument here), but (at least with regard to Campbell's argument) I'd say the opposite is true. Leaving aside that this "mass panic" myth was widely believed long before the Internet was widely used, I was quickly exposed to, and persuaded by, the likely mythical nature of my claim as a result of the interactive process of Internet journalism which I praised.

UPDATE: In Mother Jones, Adam Serwer argues that "Congress is finally standing up to President Barack Obama on targeted killing" -- specifically that they "are pushing the administration to explain why it believes it's legal to kill American terror suspects overseas." Notably, this push is coming from Republican Senators, while leading Democrats such as Dianne Feinstein are attempting to impede these efforts to bring basic accountability and transparency to this most radical power. Note the debate here: not whether the President should have the power to order Americans executed without due process, but simply whether he should have to account to Congress for what he does and what the legal framework is that he believes authorizes this.

UPDATE II: Via BuzzFeed and Spencer Ackerman, here is the logo for the U.S. Navy's executive offices for its drone planes:

Why do they hate us?

Shares