Last night Texas shocked the world with the execution of 54-year-old Marvin Wilson, a mentally retarded man with an IQ of 61. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2002 ruling in Atkins v. Virginia, which banned executing the mentally disabled, the court refused to grant a stay of execution just hours before the scheduled lethal injection.

While it’s no secret that Texas has an insatiable appetite for capital punishment (Wilson’s death marked the 245th inmate executed under Gov. Rick Perry), the state has gone to extreme lengths to circumvent the Supreme Court’s ban on executing the mentally retarded.

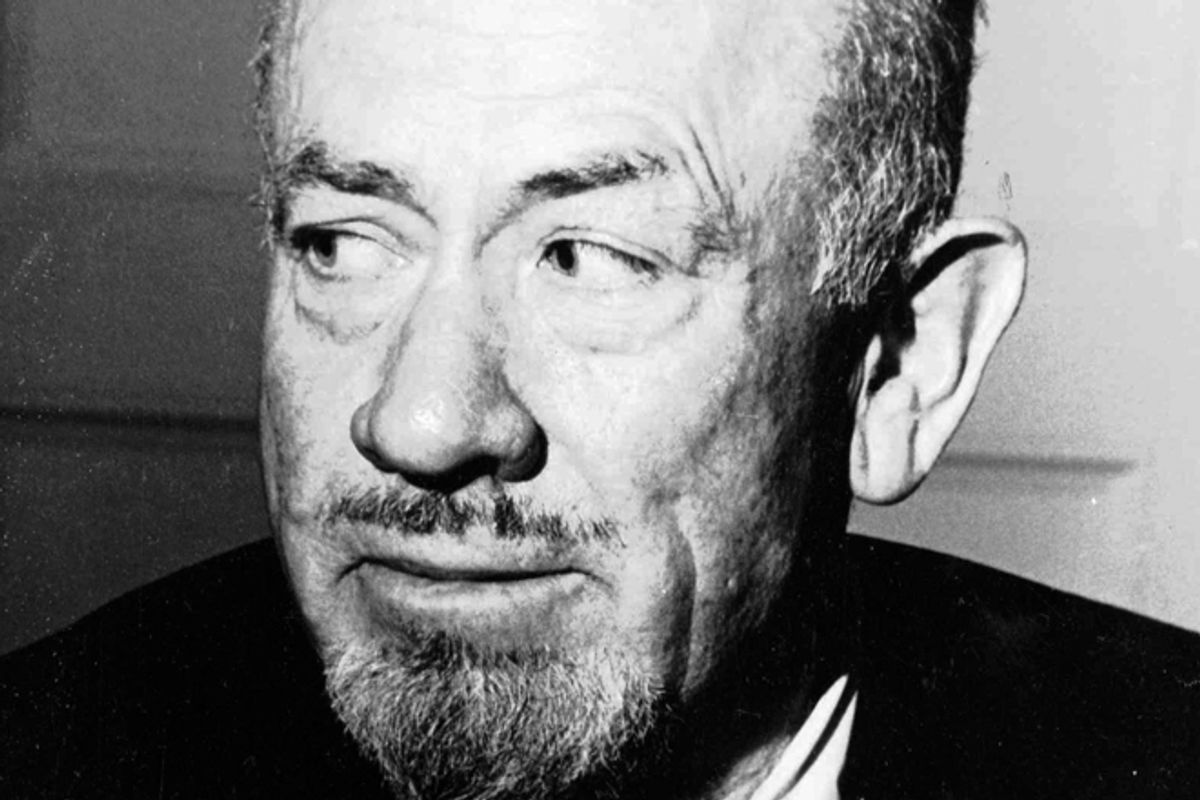

Despite having been diagnosed with mental retardation by a court-appointed neuropsychologist, Texas courts determined, based on unfounded and highly subjective standards, that Wilson was not mentally retarded and therefore was eligible for execution. Texas, unlike any other death penalty state, measures mental retardation using nonclinical standards invented by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Known as the “Briseño factors,” these standards have absolutely no basis in science or clinical application. Instead they were inspired by Lennie Small, the fictional migrant farmworker from the famous novel "Of Mice and Men," written by the late Nobel Prize-winning American author John Steinbeck.

Wilson’s attorney, Lee Kovarsky, told Salon that eight years later, not a single clinician or scientific body uses or even recognizes the “Briseño factors” as valid. “There is no citation to any science or opinion as to where those factors come from,” he adds. In fact, the only reference the TCCA made was to Steinbeck’s Lennie Small:

Most Texas citizens might agree that Steinbeck’s Lennie should, by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills, be exempt. But, does a consensus of Texas citizens agree that all persons who might legitimately qualify for assistance under the social services definition of mental retardation be exempt from an otherwise constitutional penalty?

Though Steinbeck isn’t around to comment, his family made it clear that they disapprove. In a statement released yesterday morning, Steinbeck’s son, Thomas, joined anti-death penalty advocates in calling on Texas to stop Wilson’s execution. “Prior to reading about Mr. Wilson’s case, I had no idea that the great state of Texas would use a fictional character that my father created to make a point about human loyalty and dedication … as a benchmark to identify whether defendants with intellectual disability should live or die,” declared Thomas. “I am certain that if my father, John Steinbeck, were here, he would be deeply angry and ashamed to see his work used in this way.”

Thomas Steinbeck argued that “His work was certainly not meant to be scientific, and the character of Lennie was never intended to be used to diagnose a medical condition like intellectual disability.”

Though the Supreme Court categorically banned executing the mentally disabled, it left the process of administering the ruling to the discretion of the states. While most state legislatures adopted clinical guidelines to measure intellectual disability, like those set forth in Atkins, Texas failed to pass a single statute on the issue. So in 2004, the Texas Court of Criminal Appealswas forced to establish temporary standards when faced with the death row case of Jose Garcia Briseño.

Instead of using nationally recognized clinical standards, the TCCA invented seven non-clinical and highly subjective measures, known as the “Briseno factors,” which the court reasoned would “define that level and degree of mental retardation at which a consensus of Texas citizens would agree that a person should be exempted from the death penalty.”

By using Lennie, who would qualify as having severe mental retardation, as a yardstick, Kovarsky argues that “Texas has taken the authority they think they’re delegated under Atkins and said that it allows them to exclude people with mild and moderate MR from the exemption,” people like Marvin Wilson. Despite having been diagnosed with mental retardation by a court-appointed neuropsychologist, Texas courts have determined twice under the “Briseño factors” that Wilson is not mentally retarded and therefore suitable for execution.

The “Briseño factors,” which essentially substitute scientific tools with subjective assumptions about mental disability, include whether the inmate is a follower or leader, can lie to protect his/her self-interest, and can respond coherently and rationally. However, according to Kovarsky, “Over 80 percent of people with MR are capable of thinking and responding coherently,” a statistic determined by the American Psychiatric Association.

Kovarsky put it best in a statement following the Supreme Court’s refusal to stay Wilson’s execution, saying, “The Briseño factors are not scientific tools, they are the decayed remainder of an uninformed stereotype that has been widely discredited by the nation’s leading groups on intellectual disability, including the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.”

In Chester v. Thaler, another Texas death row case challenging Briseño and pending before the Supreme Court, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities criticized the Briseño factors for being “based on false stereotypes about mental retardation that effectively exclude all but the most severely incapacitated.” The AAIDD specifically addresses the use of Steinbeck’s Lennie Small:

Atkins cannot properly be read as suggesting that states retain the right to create sub-classes of offenders with mental retardation based on whether a state believes individual claimants are as impaired as a fictional character (Steinbeck's Lennie). Instead, the Court drew a bright line, protecting alloffenders who satisfy the widely accepted clinical definition of mental retardation and excluding those who could not satisfy that clinical standard.

Without outside intervention, Texas is likely to continue defining mental retardation however it wants, allowing ignorance and fiction to determine the fate of its mentally disabled death row inmates.

As Kovarsky said in response to the Supreme Court’s refusal to grant Wilson a stay, “That neither the courts nor state officials have stopped this execution is not only a shocking failure of a once-promising constitutional commitment, it is also a reminder that, as a society, we haven’t come quite that far in understanding how so many of those around us live with intellectual disabilities.”

Shares