“Kids at play, keep the pot away!” they chanted as the procession marched along a busy boulevard in Anaheim, California. Upset over a new medical-marijuana dispensary in their neighborhood, about a hundred residents protested in front of the controversial storefront on a Friday night in February 2011. They were concerned that children would be exposed to marijuana if the dispensary stayed opened. One demonstrator held a sign that said, Yes kids, no pot.

Although medical-marijuana dispensaries were not associated with an uptick in crime and in many cases they helped to revitalize California neighborhoods, the presence of reefer retail outlets sometimes met with local resistance. Kids were a key concern. Federal and state authorities maintained that marijuana deserved special criminal sanctions because of its presumed danger to children. Anti-marijuana laws entailed additional penalties for pot crimes within a thousand feet of places where kids regularly gather, such as schools and playgrounds. “Unfortunately,” as Clare Wilson wrote in New Scientist, “the idea that banning drugs is the best way to protect vulnerable people—especially children—has acquired a strong emotional grip, one that prohibitionists are happy to exploit.”

Drug warriors claimed that tough laws were needed to keep kids away from marijuana and other illicit substances. They often warned that legalizing marijuana for medical purposes or for general adult use would “send the wrong message” to young people by implying that pot is okay. But Proposition 215 proved them wrong: There was no explosion of cannabis consumption among youth after its passage.

That’s because ubiquitous black-market marijuana was already easy for young people to get. Nearly half of America’s teenagers tried marijuana before graduating from high school and by their senior year more than 20 percent were occasional users.

Medical-marijuana dispensaries were strictly off-limits to minors. Doctors would not write letters recommending marijuana for underage patients unless they had a very serious medical problem and the consent of a parent. Some California youth “got legal” as soon as they turned eighteen. It was an open secret that nearly anyone with the right ID could visit a scrip mill and obtain a doctor’s note by complaining of poor sleep, anxiety, or headaches. For-profit clinics and physicians specializing in ersatz medical-marijuana recommendations cropped up in several states. Young adults came in droves and left with notes from doctors that served as get-out-of-jail-free cards, ostensibly exempting them from state marijuana laws—a form of harm reduction in its own right.

Ever since the 1960s, smoking pot was both a rite of passage for adolescents around the world and a way for teens to socialize. Most youth who puffed weed went through a period of limited experimentation without suffering acute harm or lasting untoward effects. The assumption that only messed-up kids used marijuana was not borne out by a 2007 Swiss study, which found that teen pot smokers were generally well adjusted and did not report more frequent psychosocial problems than abstainers. According to researchers at Cardiff University in Britain, above-average intelligence among youth is a “risk factor” for cannabis use later in life—that is, smart kids are more likely to become pot smokers.

Weed wasn’t just for losers—that was obvious from the parade of prominent actors, musicians, athletes, politicians, business leaders, and other role models who were outed as marijuana smokers. Baseball fans were nonplussed when Cy Young Award winner Tim Lincecum of the San Francisco Giants was arrested in the fall of 2009 after police found a pot pipe in the long-haired pitcher’s car. Earlier that year, a picture surfaced of Olympic gold medalist Michael Phelps taking a bong hit at a college dorm party in South Carolina. Apparently one could smoke marijuana on occasion and still be successful in sports and life.

Several guidebooks for parents—with tips on how to “drug proof” kids—explained what to look for if your child is using marijuana. Utah criminology professor Gerald Smith identified several warning signs such as “excessive preoccupation with social causes, race relations, environmental issues, etc.” A 2005 study of parental attitudes toward teen drug use, conducted by the Partnership for a Drug-Free America, found that nearly half the grown-ups surveyed would not be upset if their children experimented with marijuana. Some parents smoked pot with their sons and daughters when they got to be of a certain age. Chronic-pain patients reported that their child-rearing capabilities improved considerably when they used cannabis to ease somatic distress.

In an interview with GQ magazine, film star Johnny Depp said that if his kids were going to smoke pot, he’d prefer that they got marijuana from him rather than from someone on the street. “I have nothing to hide,” said Depp, the proud owner of Jack Kerouac’s raincoat and other Beat memorabilia. “I’m not a great pothead or anything like that . . . but weed is much, much less dangerous than alcohol.” Ironically, Depp got his start on the TV series "21 Jump Street" playing a police officer, Tom Hanson, who went undercover in high schools to bust nickel-bag pot dealers and other teenage miscreants.

It took some creative acting on the part of an attractive young cop in order to pretend to be a high school senior and convince several male students in Falmouth, Mass., to sell her marijuana, resulting in nine real-life arrests. Similar snitch scenarios unfolded in other parts of the country. The courts found it acceptable for police informants to purchase and peddle illicit substances and to use deceptive tactics, including sexual overtures, to entrap young people. School districts in several states paid students (sometimes as much as $1,000) to finger classmates who used marijuana. Police raids, drug-sniffing dogs, student locker searches, pat-downs and strip searches, closed-circuit security cameras in bathrooms, and random urine tests became part of the American high school experience—all in the name of protecting children from drugs.

From the moment Harry Anslinger began spewing invective about the evil weed, the feds maintained that pot prohibition was necessary above all to protect American youth. High school and college students were among those most affected by the war on drugs. Young marijuana users, especially ethnic minorities, suffered the highest arrest rates for possession. According to a 2006 national assessment by the American College Health Association, almost 34 percent of U.S. college students (some six million young men and women) had tried marijuana. One in five students (more than two million) said they smoked pot every month.

American officials warned that young people were putting themselves at serious risk by smoking marijuana. Cannabis, the naysayers insisted, is a harmful drug that saps resolve, destroys brain cells, causes infertility and sexual dysfunction, impairs the immune system, blurs thinking, diminishes IQ, and leads to schizophrenia and addiction. “Numerous deleterious consequences are associated with [marijuana’s] short and long term use, including the possibility of becoming addicted,” Nora Volkow of NIDA alleged. Young people were told repeatedly that today’s marijuana is super-strong—“not like the pot your father smoked.” Apparently the weed that Dad smoked wasn’t so devilish after all, so the panicmeisters had to conjure a new specter: high-potency marijuana.

The stronger stuff was good news for seasoned pot smokers, who took fewer puffs for relief and/or relaxation. But drug warriors in the United States and elsewhere depicted high-THC herb as more addictive, more brain damaging, more disorienting, more psychosis-producing, and more of a threat to youth than the relatively mellow reefer of yesteryear. Stronger pot meant more warped young minds, according to British psychiatrist Robin Murray, who ruminated on the supposed dangers of “skunk,” as high-THC sinsemilla was called in the UK, where a million and a half blokes smoked it each year. “Most people who drink alcohol, and most people who smoke cannabis, don’t come to any harm,” Murray conceded. “However, just as drinking a bottle of whisky a day is more of a hazard to your health than drinking a pint of lager, so skunk is more hazardous than traditional cannabis . . . because it may contain three times as much of the active ingredient tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).”

The skunk and whiskey comparison betrays the willful scientific ignorance of someone who has made a career out of claiming that marijuana causes schizophrenia. Numerous medical studies have proven that THC is not toxic to the human body. Unlike alcohol, it does not destroy brain cells; on the contrary, extensive research has shown that THC and other phytocannabinoids protect brain cells and promote neurogenesis, the creation of new brain cells.

Marijuana does not make one into an addict any more than food makes a person become a compulsive eater. THC, a substance safe enough to be classified as Schedule III by the federal government, is not addictive, regardless of potency, and it is incapable of causing a fatal overdose. If given the opportunity to self-administer THC, lab rats quickly lose interest (whereas rats keep lever-pressing for more heroin, cocaine, nicotine, and alcohol). The U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the British Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, the Canadian Special Committee on Illegal Drugs, and dozens of other inquiries reached the same conclusion: Withdrawal symptoms are typically mild and short-lived, even when habitual users cease taking marijuana. A person who quits smoking after a lengthy dalliance with cannabis might feel grumpy or have low energy or be somewhat depressed; he or she might not sleep well. In short, they’d feel much like they did before they started to relieve stress by puffing herb on a consistent basis. But they wouldn’t go through anything like the agony of kicking opiates or booze.

Psychological dependency is a trickier issue. “Marijuana is indisputably reinforcing for many people,” according to the Institute of Medicine, which found that fewer than 10 percent of those who try cannabis go on to use it regularly. Drug warriors who claim that pot is addictive point to the large number of kids in treatment for “cannabis-related disorders,” a NIDA-concocted syndrome of dubious clinical relevance. Most people entering reefer rehab were arrested for possession and referred to treatment by the courts in lieu of prison. Of the estimated 288,000 people who enrolled in substance-abuse treatment programs for marijuana in 2007, 34 percent of these alleged pot addicts said they hadn’t used cannabis during the month prior to their admission, and another 16 percent admitted using it three times or fewer in the month before they started court-ordered rehab.

It became a self-perpetuating myth: Kids busted for smoking pot are forced into useless, boring treatment programs, and these treatment admissions are touted as proof that marijuana addiction is rampant among American youth. When the main character in the 1998 stoner comedy "Half Baked" attends a substance-abuse meeting, he’s mercilessly heckled because hard-drug users think that so‑called marijuana addiction is a joke. “Half baked” would be an apt description of NIDA’s decision to fund a “Center for Cannabis Addiction” at the grant-hungry Scripps Research Institute. American taxpayers shelled out millions of dollars “to support research studies that focus on the identification, and pre-clinical and clinical evaluation, of medications that can be safe and effective for the treatment of cannabis-use and -induced disorders.” NIDA claimed that “therapeutic interventions” for marijuana dependence are important for adolescents and young adults “given the extent of the use of cannabis in the general population.”

Troubled adolescents who start smoking marijuana at a young age are more likely than others to become “problem users”—the small percentage of youth who obsessively seek out and smoke the herb morning, noon, and night. Onset of heavy use typically correlates with a drop in school performance, strained family relationships, and various behavioral issues. These kids are in a rut. But is their compulsive cannabis consumption the cause of their problems or a symptom of them?

NIDA broad-brushed chronic marijuana smokers with the deceptive phrase cannabis-related disorders. Recent research suggests that cannabinoid deficiency disorders might be a more apt term. Some people may be predisposed toward substance abuse by virtue of a systemic enzyme imbalance that results in pathologically low levels of endogenous cannabinoids. Scientists have linked a mutated version of the gene that encodes FAAH, the enzyme that breaks down the brain’s own marijuana, to higher levels of alcoholism and drug addiction. People with this condition may need extra cannabinoid stimulation just to feel “normal.”

For many medical-marijuana patients, a daily doobie is more like insulin than heroin. Add less psychoactive, CBD-rich cannabis into the grassroots therapeutic mix and the insulin analogy seems all the more appropriate. From this perspective, chronic marijuana use is a symptom of—if not a remedy for—an underlying imbalance rather than the cause of a syndrome of disorders.

In 2010, Brazilian scientists reported that cannabidiol helped chronic marijuana users wean themselves from high-THC habituation. Holy smokes! A cure for “marijuana addiction” had been discovered and the cure turned out to be . . . CBD-rich marijuana! Laboratory and clinical trials in several countries also showed that CBD has antipsychotic properties and reduces schizophrenic symptoms.

The causes of schizophrenia, an illness that afflicts three million Americans and 1 percent of the world’s population, are not fully understood. But researchers agree on this much: Schizophrenics are more likely to smoke pot than people who aren’t schizophrenic. That’s because many schizophrenics self-medicate with cannabis to cope with the stress of their illness. Some schizophrenics claim that marijuana decreases their anxiety, helps them focus, relaxes them, and increases their sense of self-worth—benefits similar to those reported by “normal” pot smokers. High-THC cannabis can exacerbate symptoms of an existing mental illness, just as it can amplify feelings of good mood.

Prohibitionists seized upon elevated rates of association between pot puffing and schizophrenia and twisted this into scare stories about cannabis making people go crazy. Young males were said to be especially vulnerable. The old trope that marijuana triggers mental illness returned with a vengeance, but the evidence did not support a causal link. Although cannabis use in the United States and elsewhere had increased by many orders of magnitude since the 1960s, there was no rise in the incidence of schizophrenia. The findings of Samuel Allentuck and Karl Bowman, the La Guardia Commission scientists, still rang true: “Marijuana will not produce psychosis de novo in a well-integrated, stable person.”

But what about those who are not well integrated or stable? What impact will marijuana have upon an impressionable adolescent whose sense of self is still very much a work in progress? Never one to pull punches, Dr. Tod Mikuriya maintained that marijuana is a useful, safe, and appropriate treatment for various childhood mental disorders. Given the herb’s benign-side-effect profile and its exceptional versatility, Mikuriya felt that cannabis should be considered a “first line medicine” for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive behavior, PTSD, and other mental diseases.

Some families discovered that marijuana was nothing short of miraculous for children with severe autism. Long known as an effective anticonvulsant, cannabis was particularly helpful for autistic kids who also suffered from seizures. A spectrum of diseases that affects more than 1 percent of American children, autism is found among all social strata in every part of the world. Worried about the toxic side effects of Risperdal and other antipsychotic meds prescribed for kids with autism, a few desperate parents turned to cannabis.

Marijuana muffins proved to be a life-safer for Joey, a severely disabled African American boy in Los Angeles who had been diagnosed with autism when he was sixteen months old. At age ten Joey weighed forty-six pounds and could not speak or walk. He was on six powerful pharmaceuticals that destroyed his appetite, ruined his sleep, and wasted his body. The doctors told his mother, Meiko Hester-Perez, that longevity was not in the cards for Joey. Meiko, who had never smoked cannabis, would do anything to help her son, even if it meant breaking federal law. Meiko’s uncle, a career LAPD officer, frowned upon marijuana, but he, too, was impressed by the dramatic changes that occurred after Joey started eating ganja edibles. The mute, autistic child became more responsive and more energetic, his body weight nearly doubled, and he took fewer Big Pharma meds. Cannabis “is an alternative for parents who have exhausted all other means,” said Hester-Perez. She formed a group called the Unconventional Foundation for Autism, which emphasized marijuana therapy as a treatment option for autistic children.

The Internet was buzzing with testimonials from parents who touted the benefits of medical marijuana for adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a diagnostic label applied increasingly to school kids who behaved in a manner that irritated and frustrated teachers and often alienated other students. Medicinal cannabis was showing up in classrooms, according to a 2010 Christian Science Monitor article, which reported that “high schoolers are bringing pot to school, and they’re doing it legally. Not to get stoned, but as part of prescribed medical treatment.”

But the thousand or so school kids who were eating cannabis edibles under a doctor’s supervision paled in comparison with the almost four million American youth diagnosed with ADHD who were on addictive amphetamines such as Ritalin and Adderall, which cause neurological damage, heart attacks, and sudden death in children. Another 1.5 million American kids were taking risky pharmaceutical antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics that worked no better than a placebo—drugs that were far more mind-altering and dangerous than marijuana. Big Pharma antidepressants and ADHD pills—unlike cannabis—figured in scores of emergency room visits. The mass overmedication of American youth was the flip side of the war on drugs.

Amphetamines can often quell the fidgety, impulsive symptoms of ADHD, but speed doesn’t address the underlying disorder, which has been linked to food additives and environmental pollutants. In addition to recommending dietary changes and less screen time, a handful of physicians risked the wrath of the California Medical Board when they began treating difficult ADHD kids with cannabis. For some children, the herb was much more effective than corporate pharmaceuticals—without any nasty collateral effects.

For kids with attention deficit disorder, pot doesn’t impair—it helps them focus. “My son was diagnosed with ADHD when he was six,” a woman from Grass Valley, California, acknowledged. “He was hyperactive and had trouble in school, but we didn’t want to put him on Ritalin. Too many side effects. When he got to high school, I suddenly noticed that he’d calmed down and could concentrate. I couldn’t figure it out. Then he told me that he started smoking pot.”

The rise in marijuana’s popularity among American youth since the late 1960s coincided with a surge in diagnosed cases of attention deficit disorder and its hyperactive variant, ADHD, a condition that Dr. Tom O’Connell likened to a “pediatric anxiety syndrome.” A retired thoracic surgeon and former captain in the U.S. Army Medical Corps, O’Connell had treated hundreds of wounded American soldiers during the Vietnam War. He came out of retirement in 2000 and began seeing medical-cannabis applicants in Oakland. Over the years he would compile a database and analyze usage patterns of six thousand patients. His findings would challenge both prohibitionists and drug-policy reformers who concurred that reefer ought to be a no‑no for under-twenty-one-year-olds. “Each side in the modern pot debate is wedded to its own fairytale,” O’Connell blogged. He bemoaned that reform leaders “were nearly as clueless as the Feds—and equally susceptible to doctrinaire thinking when it comes to adolescent drug initiation and usage.”

Why do some young people who experiment with cannabis become daily users? Are their claims of medical use credible? Dr. O’Connell found that the vast majority of medical-marijuana applicants were already chronic users before they walked through the door of the dispensary. (People who try marijuana and have an unpleasant experience generally don’t go to physicians for letters of recommendation.) The everyday smokers he interviewed had remarkably similar medical and social histories. O’Connell determined that the main reason young people smoke pot on a regular basis is because it is a safe and effective way to relieve anxiety and other mood disorders associated with insecurity and low self-esteem.

Repetitive drug use usually entails a more serious purpose than mere recreation, according to O’Connell, who maintains that since the 1960s young Americans have embraced marijuana en masse to assuage the same emotional symptoms “that made anxiolytics, mood stabilizers and antidepressants Big Pharma’s most lucrative products.” “The need to self-medicate symptoms of adolescent angst is much more important than simple youthful hedonism,” O’Connell concluded.

For America’s youth, cannabis was like catnip for a cat, a poorly understood but nonetheless efficient herbal means of navigating the ambient anxiety and frenetic complexity of modern life. The emergence of marijuana as the anxiolytic drug of choice and its durable popularity among tense teens and anxious adults made sense in light of scientific research that has documented the stress-buffering function of the endocannabinoid system.

Whereas activation of the body’s innate stress response (“fight or flight”) is essential for responding and adapting to acute survival threats, too much stress can damage an organism in the long run by depleting endocannabinoid tone. A compromised endocannabinoid system sets the stage for a myriad of disease symptoms and ups the risk of premature death. Chronically elevated stress levels boost anxiety and significantly hasten the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia. Emotional stress has been shown to accelerate the spread of cancer. Stress alters how we assimilate fats.

On a cellular level, stress is the body’s response to any change that creates a physiological demand on it. When a person is stressed, the brain generates cortisol and other steroid hormones, which, in turn, trigger the release of naturally occurring marijuana-like compounds: anandamide and 2-AG. These endogenous cannabinoids bind to primordial cell receptors that restore homeostasis by down-regulating the production of stress hormones. Marijuana, an herbal adaptogen, essentially does the same thing.

Twenty-first-century children are under assault from an unprecedented array of debilitating stressors, including junk food, electromagnetic radiation, information overload, and a noxious swill of eighty thousand unregulated synthetic chemicals, all of which wreak havoc on metabolism and brain development. The cumulative effect can be seen in skyrocketing rates of childhood obesity, ADHD, autism, hypertension, depression, and strokes among adolescents. For all the talk about protecting the children, kids haven’t been faring very well in America. Among twenty developed nations, the United States and Great Britain ranked as the two worst places to be a child, according to a 2007 UNICEF study that assessed six criteria: material well-being, health, education, relationships, behaviors and risks, and young people’s own sense of happiness.

Economic inequality is socially divisive, emotionally stressful, and hugely damaging in terms of health outcomes, especially for the poor, who comprise 50 percent of the population in early twenty-first-century America. Massive inequalities disgrace and sicken the United States. Extensive research has shown that health and social problems by almost every measure—from mental and physical illness to violence and drug abuse—are more prevalent in countries with large income disparities.

With millions of stressed-out teens smoking pot, some parents are apt to attribute their children’s problems to marijuana’s malevolent influence. The adult temptation to blame the weed is reinforced by public officials who continually inflate the dangers and deny the benefits of cannabis. But U.S. authorities have long since forfeited any claim to credibility with respect to marijuana. The facts, meanwhile, speak for themselves: Carcinogens in our food, water, and air are legal; cannabis is not.

Marijuana prohibition is symptomatic of a deep cultural pathology. Its persistence as government policy is indicative of a body politic with a failing immune system, a society unable to heal itself. There is no moral justification for a policy that criminalizes people for trying to relieve their suffering. Reefer madness has nothing to do with smoking marijuana—for therapy or fun or any other reason—and everything to do with how the U.S. government has stigmatized, prosecuted, and jailed users of this much maligned and much venerated plant.

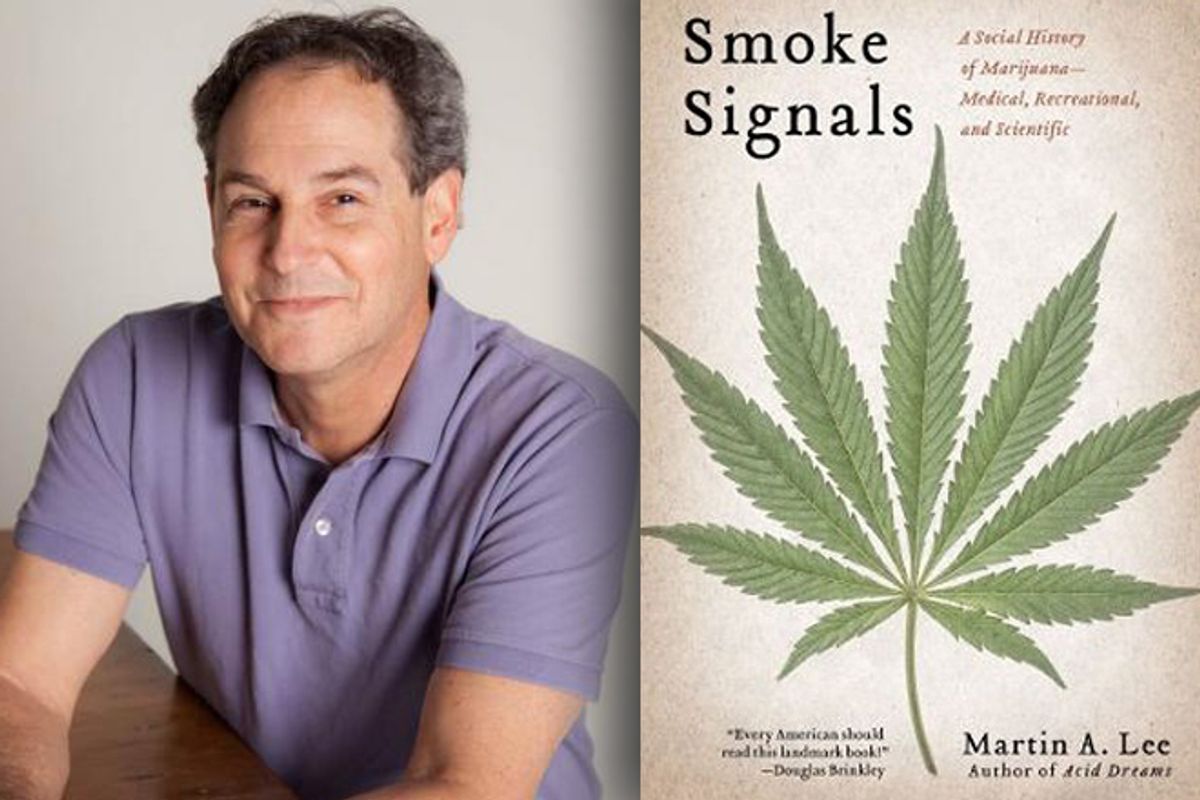

Excerpted from "Smoke Signals: A Social History of Marijuana -- Medical, Recreational and Scientific" by Martin Lee. Published by Scribner. Copyright 2012. Reprinted with permission of the publisher and author.

Shares