While a draft plank in the Republican Party’s platform supporting a constitutional amendment banning abortion has gotten plenty of attention, so far unnoticed is another culture war provision tucked right alongside it -- an opposition to federal funding for embryonic stem cell research. “We oppose the killing of embryos for their stem cells. We oppose Federal funding of embryonic stem cell research,” the draft language reads, mirroring previous years' platforms. You’d be forgiven for having déjà vu from 2004, when stem cell research was at the top of the agenda of both parties and sparked fierce and emotional debate. It’s completely vanished from the political scene since -- what happened?

Stem cells used to be one of the big three social issues dividing Americans, along with abortion and gay rights. It was a "cultural debate engulfing our country today,” as then-Kansas Sen. and now Gov. Sam Brownback, a staunch social conservative, said in 2004. The issue played a major role in that year’s presidential race, with Democrat John Kerry suggesting that “millions of lives” were at stake by President Bush preventing federal funds from going to the medical research. Bush, buoyed into office by the Christian right, opposed the taxpayer dollars going to the research because it involves the destruction of embryos, which some social conservatives equate with abortion, and thus murder. Bush issued the first veto of his presidency on a 2006 bill passed by Congress to expand stem cell research, and the topic was a reliable piece of the “Bush-Rove machine,” along with gay marriage, as columnist Frank Rich noted at the time.

But this year, as in 2008, stem cells are completely absent from the presidential election, despite the cycle being unusually dominated by touchy social issues like abortion, in the wake of Rep. Todd Akin’s comments. A Nexis search of news articles from 2004 and 2006 for embryonic stem cell research returns more than 3,000 results for each year. So far this year, there were only 724 stories written on the subject.

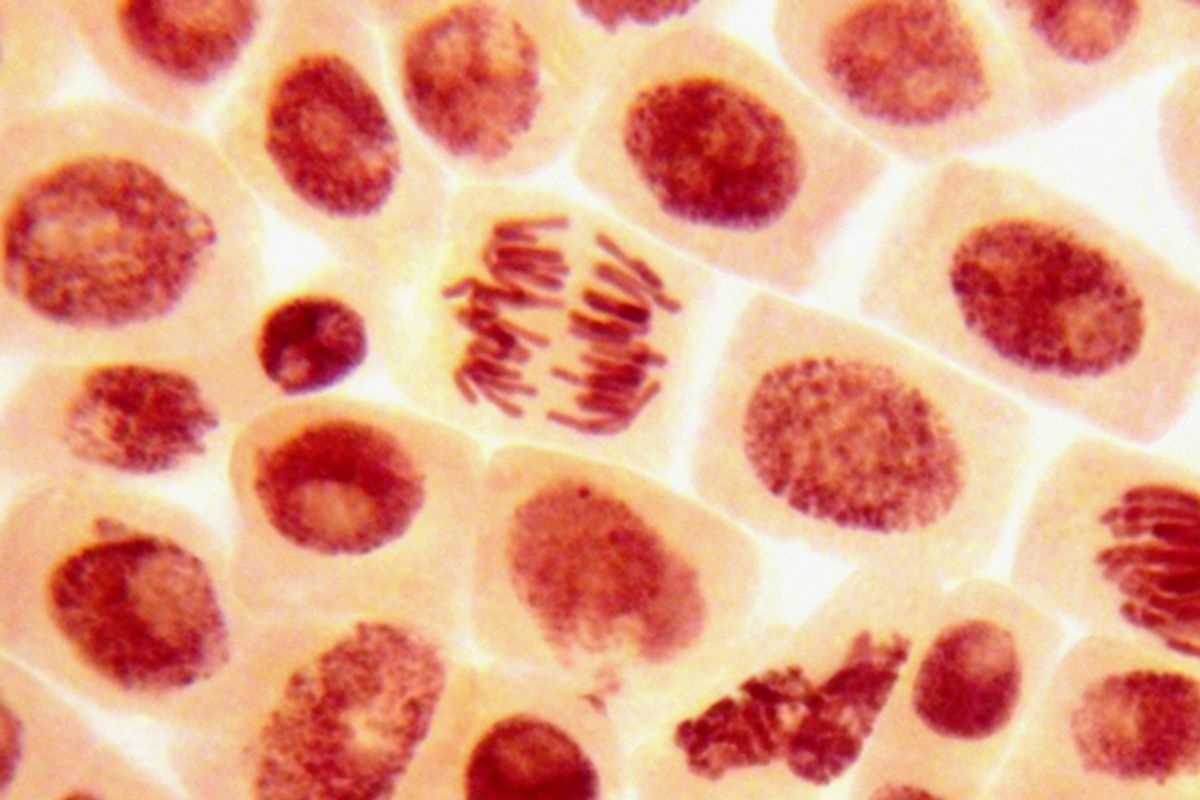

What changed? Two things -- one scientific, and one political. First, there were great advances in the way the science is conducted, lessening the need for the destruction of new embryos. In 2007, scientists first reported developing human Induced pluripotent (iPS) stem cells. IPS cells are adult cells that have been “genetically reprogrammed” to behave like embryonic stem cells. They possess many of the same qualities of embryonic cells, and when they emerged, iPS cells were heralded as a replacements for embryonic stem cells -- all the scientific benefit with none of the controversial political complications. Bush and other social conservatives had long supported stem cell research, as long as embryos were kept out of it, and iPS seemed to offer that solution. Even though research now suggests iPS cells may not ultimately be an effective replacement for embryonic cells, both for scientific and funding reasons, the advent of the cells effectively deescalated the debate over research and helped move it to the back burner.

Meanwhile, as the scientific paradigm was altered, so too was the political calculus. Despite the best efforts of social conservatives to use the issue as a campaign tool, Republicans have found that their party is deeply divided internally on the issue and unable to win on it. Nancy Reagan famously came out in 2004 in favor of expanded research, while her son, Michael Reagan, spoke at the Democratic National Convention in support of the science. Both saw hope in the research for people like their late husband and father, who suffered from Alzheimer's. Despite expectations, the battlefront on the issue didn't fall along traditional pro-choice/pro-life lines. A number of staunchly anti-choice senators like Orrin Hatch and Trent Lott voted in favor of the 2006 bill that Bush vetoed. Republican Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist even wrote an Op-Ed in the Washington Post opposing Bush’s policy on stem cells and called for an expansion in the number of embryonic lines available.

Dominique Brossard, who studies public perceptions of controversial scientific topics at the University of Wisconsin, which holds many of the usable embryonic cell lines, said she was surprised the Republican Party platform would include language on stem cells in 2012. “I was surprised to hear that they were going to add that issue because as far as public opinion is concerned, this is an issue that wasn’t really defined by party lines,” she told Salon.

In 2006, the country saw a clear case study of what happens when an election becomes about stem cells, and it did not go well for opponents to the research. Just as Claire McCaskill may hold onto her Senate seat this year because of an opponent’s retrograde views on one social issue -- abortion -- her opponent's views on stem cell research are widely credited with helping her win her seat in the first place six years ago. As baseball fans tucked into beers and wings at bar stools and couches across Missouri to watch their underdog St. Louis Cardinals take on the San Diego Padres in the first game of the National League Division Series on Oct. 21, 2006, they saw a powerful message about a different contest just weeks away. Visibly shaking and clearly struggling with his words from the late-stage Parkinson's disease he was fighting, Michael J. Fox told Missouri voters that electing McCaskill would help millions of Americans “like me.” Research showed the ad to be highly effective, and when Rush Limbaugh attacked Fox -- he must be "either off his medication or acting,” Limbaugh said of Fox’s shaking -- the ad exploded into a full-blown national controversy. McCaskill squeaked by in one of the nation’s closest Senate races, helping Democrats take control of the Senate by a single seat.

So while the national public polling has not changed dramatically -- support for embryonic research is up 4 percent, to 58 percent, according to Gallup -- the political dynamics for the GOP have moved. The party may have been divided for some time, as a Gallup poll from 2004 showed Republican voters were split almost evenly 36 percent to 37 percent, on one question of research, but that left a third of voters unsure, and in the vacuum, Bush, as leader of the party, was able to set the agenda. But after Republicans’ 2006 drubbing, and particularly McCaskill’s win on this issue, and with no leader like Bush opposing research, the party likely realized they had nothing to gain for fighting on this issue, and thus abandoned it. “It’s no longer a really good issue for the Republican Party. It's low reward and high risk," Jason Owen-Smith, a sociology professor at the University of Michigan who has studied the debate, told Salon.

The last time stem cell research got much attention in Washington was in 2009, when President Obama signed an executive order dismantling many of the barriers put in place by Bush on federal funding for the research. While there was initially some debate over the National Institutes of Health's new guidelines, when they were finalized, “this kind of became a closed issue," Owen-Smith said.

But that doesn't mean it's necessarily closed forever. Romney hasn’t offered a clear position on embryonic stem cell research. Researchers are worried about the prospect of a Romney presidency. Eli Adashi, a professor and former dean of medicine at Brown University, who has advocated for greater freedoms on scientific research, said the Republican Party platform plank on stem cell research is troubling. He told Salon that, if enacted into law, it would be a “death blow” to the stem cell research and the burgeoning stem cell pharmaceutical industry. He also said that young researchers choosing which field to specialize in are often turned off from pursuing stem cells because of fears that the field would be jeopardized every four years with possible election of a Republican in the White House.

Legislation supported by presumed vice-presidential nominee Paul Ryan is even more troubling. The constitutional amendment supported by the GOP platform and Ryan to give fetuses the same rights as humans could be construed to not just prohibit federal funding of research, but any kind of research, public or private, that involves the destruction of embryos. “The platform plank they’re putting together -- it’s hard to see how that would amount to a full-on ban on research, and maybe criminalization of the research,” Owen-Smith said. Zack Beauchamp at ThinkProgress argued that voters need to pay more attention to stem cell research and possible fall out of a Romney presidency, calling it the “sleeper issue of 2012.”

“Because it’s a technical debate, and because it keeps dropping on and off the radar screen, I don’t think we’ve ever had the debate we need to on this issue,” Owen-Smith said. If Romney wins, count on hearing more about it.

Shares