Last week, my fellow Hyperallergic editor Kyle Chayka wrote a post about video artist Wendy Vainity, who makes bizarre, creepy, and sometimes funny 3D animations. Chayka began by posing a question: Does Wendy Vainity actually know what she’s doing?

I found this lead-in curious, as it’s not clear what the alternative would be: that Vainity doesn’t know what she’s doing? That she somehow made her videos and posted them on YouTube without being fully conscious? I’m not sure. Chayka draws out his point later in the post. He writes:

Are the videos outsider art, or the work of a knowing artist making amazingly weird work on purpose? Wendy Vainity might be the Henry Darger of the web, an artist working outside of the mainstream but creating something so strangely compelling that you just can’t look away.

For some reason, I became oddly frustrated with the distinction drawn in that first question, of whether Vainity is an outsider artist or just a knowingly — and the subtext here is “self-consciously” — strange one. I’ve long loved so-called “outsider art,” and I’ve never had much trouble with the label, but last week it suddenly offended my sensibilities. I felt like Chayka was giving Vainity short shrift by questioning her awareness.

I’m sure that wasn’t actually what Chayka meant to do, but the whole episode got me thinking about the line we draw between outsider art and — well, just plain art, which has never been deemed in need of a permanent descriptor.

What makes someone an outsider artist? Is it a question of simply being outside the art world establishment? Is it a matter of influences: someone who has studied art history and consciously absorbs the work of other artists, versus someone who makes his or her art in a vacuum? Or is it, as Chayka implies in his post on Vainity, about intentions and distance — whether the creator is purposely diverging from the mainstream or just translating his or her weird vision of the world into art?

When you break them down, none of these definitions really work. If you follow the first, you end up with vast numbers of outsider artists and a fluid category that artists can pretty easily leave behind. The second seems a bit more feasible, but also sort of false: while some artists may not follow the developments of the art world, it’s hard to find anyone truly working in a cultural vacuum these days — especially someone who uses the Internet, or at least YouTube, like Vainity. As gallerist Frank Maresca, co-owner of Ricco Maresca Gallery, put it when discussing the work of self-taught artist William Hawkins in an interview with New York Social Diary:

We consider William Hawkins to be a self-taught artist … [he] was operating outside of the art-historical continuum. He was not influenced by any other artist. But it doesn’t mean that he wasn’t influenced by popular culture.

I struggle with the third distinction the most. If someone makes a work of captivatingly weird art, if the final product is great, does it matter whether the gesture was self-conscious or in earnest? How much does — and should — the artist’s intentions affect how we receive his or her work? I don’t know.

In a blog post from 2007, dealer Edward Winkleman discusses the issue of intent and his changing perceptions of outsider art:

Being the stubborn loggerhead I am, I can’t get myself unstuck from an assumption about the importance of intent in art. Especially intent with regard to communicating.

Taken to its logical extremes in our debate, however, this assumption has led me to conclude that the work of Henry Darger, for example, is not “Art” because (or so it’s been reported) he had no intention of ever showing it to anyone, meaning it was not created with the intent of communicating anything with anyone, and that then made it something other than “Art.”

Now I can look at Darger’s work and feel my jaw involuntarily drop. I can marvel at the vision. I can delight at the composition and especially the color. But because I know (or think I know) these works were the result of a masturbatory effort, they don’t meet my own definition of fine art, which goes beyond just intent to communicate to include what bnon called, in the thread on child prodigies yesterday, the act of “submerging [one]self in art history as well as surveying the contemporary field and carving out a niche.”

Winkleman goes on to bring in some sources that complicate his notions of what capital-A art can be, but he seems to maintain the importance of intent to communicate — which in turn seems problematic to me, because I don’t quite get why it holds so much weight. If someone wrote poetry and kept it locked in a drawer, never showing it to anyone, we’d still consider it poetry. Does art require communication, or is the act of translation enough?

What’s more, a figure like Forrest Bess complicates these divisions. Bess both made artworks that were direct renderings of his intensely personal visions and engaged with the broader art world, exhibiting his paintings and corresponding with dealers. He was an outsider but also a quasi-insider — maybe an outsider who wanted to be an insider. Where does that leave him?

In his aforementioned interview, Maresca offers his own interesting take on the outsider artist definition. He says it only applies to people who can’t function independently:

I don’t particularly like the term ["outsider art"], I’ve never really liked the term … Mostly everyone that I know when you mention a person who is an outsider, they don’t think of someone who is operating so far outside of society (as we know it) … [that] they need to be with caregivers — that is [my] definition of outsider art — in the same way that the artist Dubuffet defined it essentially as the art of the insane.

In a way, even though this definition may seem extreme, it strikes me as for more logical than any of the others. It draws a clear line; it could be that I’m attracted to that tidiness.

There are some people, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith among them, who have argued for a while that the label itself is moot. Smith opened her review of a 2007 exhibition of work by Mexican artist Martín Ramírez with these lines:

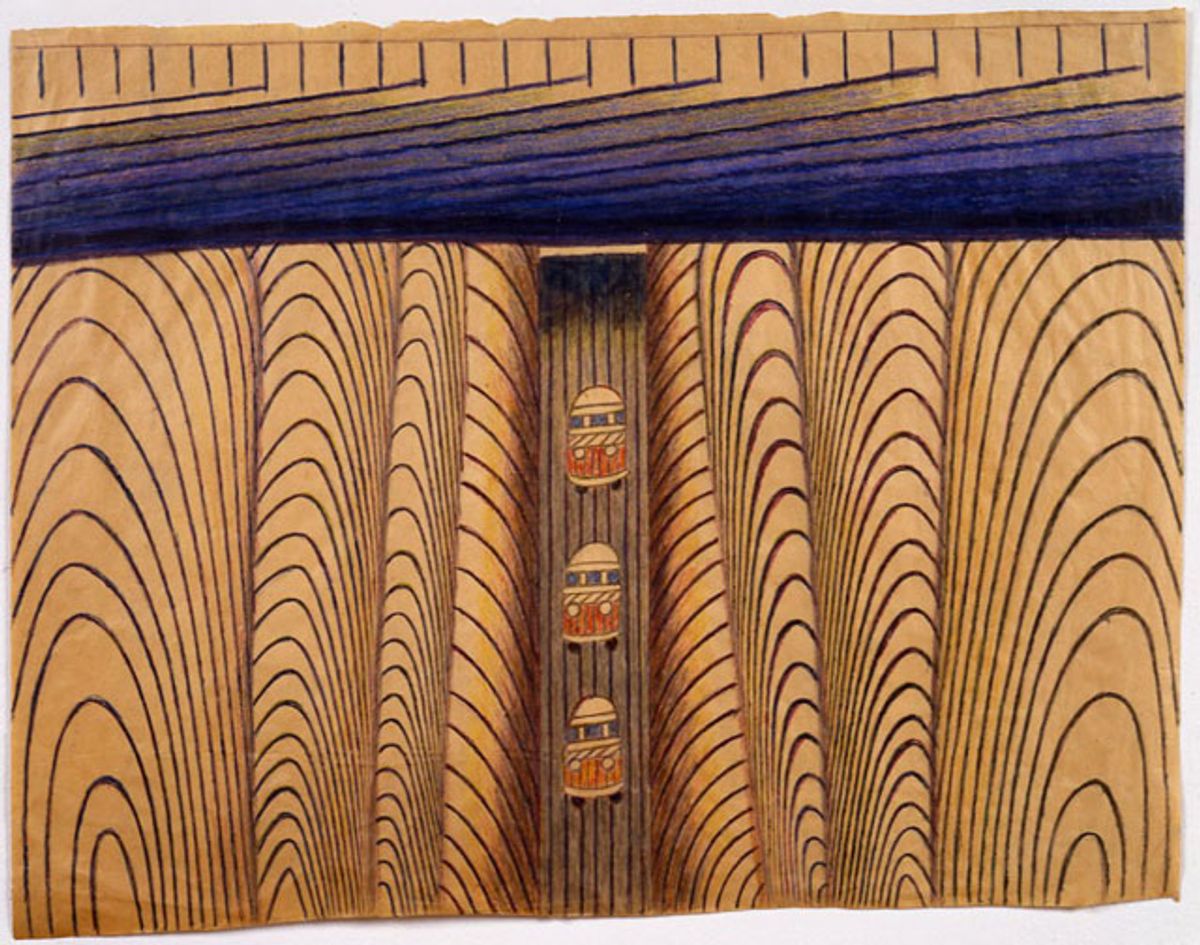

The American Folk Art Museum’s transporting exhibition of the scroll-like drawings of the Mexican artist Martín Ramírez (1895–1963) should render null and void the insider-outsider distinction.

Although my gut still clings to “outsider art” in a romantic way, I think ultimately my brain aligns with hers here. We increasingly use the term as shorthand for a certain visual style, so in that sense it may still have some value, but otherwise I’m not sure what it does beyond relegating these creators to special art ghetto. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t wonder and ask about their intentions — that information always gives us a better, fuller picture of their work. But did Wendy Vainity know what she was doing when she made her videos? Of course.

Shares