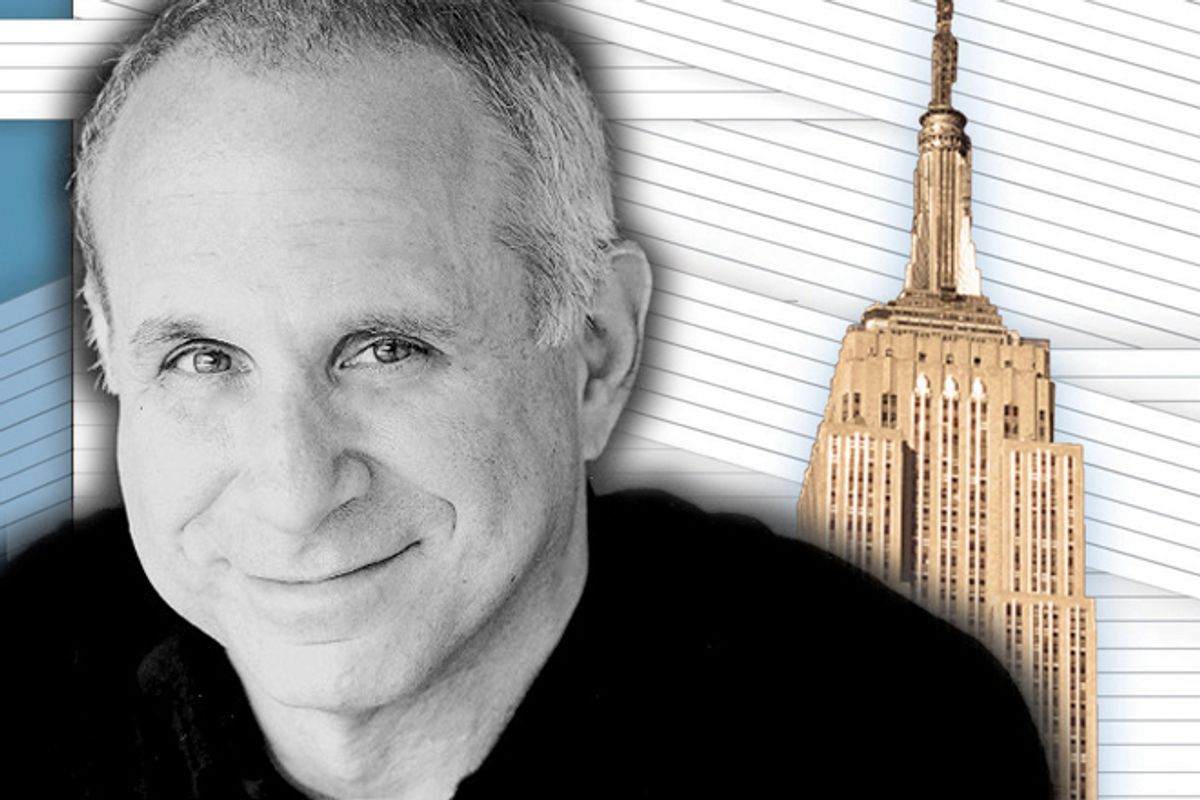

“These Things Happen,” the stunning debut novel from Richard Kramer, the Emmy and Peabody award–winning writer, director and producer of such praised TV classics as "Thirtysomething" and "My So-Called Life," is the kind of book that defies easy categorization. Published this month by Unbridled Books and written from multiple points of view, on its surface "These Things Happen" is the story of Wesley Bowman, a thoroughly fascinating and preternaturally — but never preciously — intelligent New York kid whose beating at the hands of gay-bashing bullies in the basement of his schmancy Manhattan prep school (the sort of place where “these things” are not supposed to “happen”) at once brings his family together and pushes them apart in unexpected ways.

Yet it’s also the story of Wesley’s equally brilliant best friend Theo, the newly out class president who was the bullies' real target. And it's the story of Kenny, Wesley’s father, a lawyer whose tireless advocacy on behalf of the gay community masks a deep ambivalence about his own sexuality, and of George, Kenny’s partner, an aging actor who provides an unlikely model for the kind of man — or really, the kind of mensch — Wesley is striving to be. It's also the story of Wesley’s mother, Lola, and her husband, Ben. And so it goes.

Most of all, it is a novel of almost-shocking empathy and incredible love. “It’s a coming-of-age story and a coming-out story,” Kramer tells me in the following conversation, but the coming out here isn’t so much a declaration of sexuality as a declaration of identity. In "These Things Happen," the only people we have to come out as is ourselves, to ourselves. What more needs to happen than that? I spoke with the writer last week.

One of the most striking things about the novel is the way we see the difference in experiencing gay identity and coming out among the generations. Teenage Theo, who seems relatively un-conflicted about his sexuality, is different from a character like Wesley's father, Kenny, who married and had a family before coming out as an adult.

I never thought of Theo or Kenny as emblems. I just wanted to tell this story and not think about it while I was writing it. That’s the best writing advice I ever got; I was fussing around about something or other during "Thirtysomething," and [creator/executive producer] Ed Zwick shouted at me, “Just write it! Don’t think!” I keep those words taped to my screen.

As I think about the book – which I can do now, it’s done! — I see from the evidence that I wanted it to be a coming-of-age story, but not just about teenagers, and a coming-out story, but not just about gay people. Coming-of-age is active; it doesn’t just happen. At different points in life you find things in yourself you didn’t know were there, and you choose what you’re going to do with them and what you’re going to let them do to you. Can you accept what you find? Can you look at the sum of it – at your life — and stand behind it, choose it? This is a choice we don’t always know we can make. George knows, though; he's the one who seems to be the “lightest” in this batch of smartypants New Yorkers. And knowing this, he gives the truest gift to Wesley, his partner’s son, who is not “his” but ultimately becomes his, too, in a special way. By the end, all the adult characters come to know what George knows. That to be able to look at your life, all that it is, and choose it – no matter what the bullying, hateful discourse around certain choices might be – is a heroic action.

As for coming out, we think we know what it means, but can it mean more? Can you keep a secret from yourself, one you’d never want to know? I think you can. It doesn’t make you a shitty person. As a friend of mine says, the unexamined life is worth living, and there’s parking in the building. Then, sometimes, these things happen that blow open the hidden internal door. And what’s behind it may be just the thing from which you think you’re safe. But no one is.

The homophobia in the book seems to come from places where it isn't supposed to exist: Lola, Wesley's book editor mother; Kenny’s internalized shame; the gay-bashing bullies in the basement of a liberal Manhattan private school. What is it about this particular prejudice that makes it so hard for otherwise well-meaning people to shake?

Wesley’s mom edits famous authors. She’s kept more than cordial relations with her ex and his partner, subscribes to the Manhattan Theatre Club with them, cries at gay weddings on the High Line. And she lives in the United States, where for complex reasons the idea of Innocence has become ruthlessly sentimentalized (and politicized) and where it’s “proven” every day that gay men are a danger to it. Gay men who’ve read the book tell me it’s made them realize their own cautiousness with the boys in their life who, in most cases, are still the sons of other people. Don’t let the look linger. Smile, but from a distance. How can Lola be bigger than that discourse? It’s insidious; it has the power of two thousand years behind it; no one can be bigger than it. But I wanted the people in the book to see it, too, and face it. That’s the start of being able to take it apart: to see it. Lola does; it almost blows her apart. But she admits it. I love her for that.

As for Kenny, this “straight-acting” paragon who advised Governor Cuomo three times a day on the gay marriage bill, who is Elaine Stritch’s lawyer – how could he be homophobic? Maybe that’s not the right word; maybe we need a better one. Kenny will do anything for an oppressed gay person, but that doesn’t mean he’d be happy if his own kid turned out to be gay. Because how could anyone want or choose that for themselves or for someone they love? Kenny actually says words to that effect. I love him for that; it takes balls for someone like him to admit to an attitude that he’d be condemned for in his circle. That he’s able to see it, detach it from himself and show it – I think that’s the start of changing it. As for the gay-bashing in the basement of the fancy private school, I checked with several New York anti-bullying groups to see if it was realistic. All told me it was. Bullying, especially gay-related, has a wide socio-economic wingspan.

It does seem like we're swiftly making progress on the equality front: You've got the joke about going anywhere in New England except for Maine, and now Maine voters just passed marriage equality. What do you think the world will be like for Wesley and Theo as they grow up, and for their kids? And what do you think will happen to the kind of (for lack of a better word) "traditional" gay culture — the Sondheim, the ability to quote at will from "The Glass Menagerie" — that George seems to embody?

I love how the world is changing, even as so much of it seems to stay the same. I think there will be an ongoing tension for many years to come. The world I’d like to see for Wesley and Theo and their kids is not necessarily one where Gays Have the Right to Marry but one where in gym class the budding gay kid who isn’t into climbing up ropes is cheered on by the other boys, who stick around afterwards to show him how to make it a little easier and who express curiosity as to what it’s like to be him. Maybe he could teach them how to sing "I Dreamed a Dream" or whatever piece of dreck passes as a good theater song in 40 years. Stereotypes, sure, but no gay man of my time -- and, from what I’m told, few now -- experience an inclusive kindness that would teach them, early on, that to reveal their essential selves is safe, not dangerous; that who they are and what they care about is valued and wanted. I had a taste of what this would be like today, waiting for a plane at Logan Airport. Someone had left behind a travel magazine. I saw there was an article by Greg Louganis in it. Hmmmm. Gay Greg? He writes for a travel magazine? Then I also saw there was an article about great GLBT travel destinations. I reached for the magazine, and as one learns to do I hid its contents because God forbid anyone should see what I was looking at. I saw that I’d found a gay magazine, and my first thought was – forgive me – “Some fag left this behind. I wonder if I can guess which one he is.” Then I saw the sticker on the cover: Property of US Airways. And I felt a bit of a shift in the bit of ground beneath my feet.

As for traditional gay culture – may it live forever. It’s beautiful, it’s funny and it’s useful to people; it certainly has been for me, and I like sharing what I know, as George does with Wesley. I would like to see gay men value the gold they’ve gathered, not feel that they have to mock it. We all need "The Glass Menagerie"; I’d like to see a world where every high school kid is required, for graduation, to recite Tom Wingfield’s opening speech, do a decent Eartha Kitt impersonation and know how to sing at least one of the songs cut from "Company" in Boston. My brave new world explodes the boundaries between what is ours and what is theirs; we’re each missing out on a lot. I guess we’ll see.

Over the last several years, there's been a kind of overarching narrative in our culture about the urban non-traditional family -- the idea that you choose your family, "Sex and the City"–style. The book kind of takes this trope and turns it inside out: Just because all these people are smart and interesting and living interesting lives doesn't mean that everything is perfect and wacky and everyone always gets along. Did you think about creating a conscious corrective to that kind of hip NYC utopia?

I don’t think we make our own families, and if I ever did, I don’t anymore. It’s a lovely thought, and there are some terrific works of art that embrace it, such as the "Tales of the City" books [ed. Note: Kramer wrote the acclaimed Showtime miniseries based on Armistead Maupin’s books], which dramatize it comically and movingly. But I think that’s a young person’s notion. What I wanted to say in "These Things Happen" is that family is not something you make but something you constantly redefine and rediscover. It is greater than the sum of the people in it, chosen or not, and it includes the accumulated memories, experiences and beloved ideas that add up to make a life. Your life. And what matters – as George says – is whether you can say, finally, that you choose it and embrace it.

You’ve had an incredibly distinguished career in television. What made you want to write a novel now?

"To Kill a Mockingbird" made me want to write a book. I read it just a few years after it was published, when I was Jem’s age. Harper Lee found me, in Nassau County. “Maycomb,” she wrote, “was a tired old town, when I knew it …” I didn’t know about voice, but I knew voice when I heard it; those words came from someone, unseen but there. At the end, as Scout tells how Atticus would sit with Jem all night and how “He would be there when Jem waked up in the morning” – well, there it was. Those words bring tears to my eyes, even now, 50 years later.

And the genesis goes back 25 years. I was working on a show. Each night I’d go to the same restaurant; the same guy always greeted me, brought me my focaccia and spaghetti aglio e olio. And after years of this, I realized I didn’t know his name. I’d never taken the trouble to learn it; he was useful, not real. And seeing this shook me. I told him; he said no one knew his name. His name was George, though, and this was the start of George, the main character. He stuck with me for decades, a piece in search of a puzzle. As a few more pieces fell from the sky, I realized I wanted to write about the person who takes the picture of the party at the table but is never in the picture himself. He is invisible, and partly by choice. I didn’t know I was writing about myself until I had finished the book. If I had, I’m not sure I could have written it.

How do you go about creating a character? Was the process different in a novel than it has been in your TV work? Was there backstory that didn't make it into the book?

In a TV or a movie script you have a very few pages in which to force a character to do some pudgy, significant thing that will move the plot along; someone once told me to think of character as a cracker on which a story is spread. That leads to some pretty crumbly characters. Here’s the big difference: In TV, you “create” a character by mutual agreement; those on the committee including the producers, the studio, the network, the casting people, the other cast members, the audience, everyone has an opinion. (An 8-year-old actor on a friend’s hit show informed him that, in his opinion, the girl who had just read for the part of the kid’s pre-teen crush was “underwhelming” and “result-oriented.” Could they see some other options?)

With a book: There’s you, and then there’s you, and the next day there’s you all over again. It’s an intensely intimate experience creating a character in a book because, as I say, they’re all you. At the end of a day of work on "These Things Happen," I felt like a fully balled melon; I had nothing left, and I believed as I sat there that I would never have anything again. I never felt that way on "Thirtysomething" or the other shows. With those, it was professional. This was personal. And I preferred it that way, I found. A lot of people can learn what makes a good act break; only I can learn what it is to be me.

As for discarded backstory, there’s plenty. But the characters have asked me to maintain, at least a little, of a shred of privacy. Wait for the DVD.

Shares