They lasted just five years. They made just four proper albums. They've been ignored by the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. The American pop charts wanted nothing to do with them.

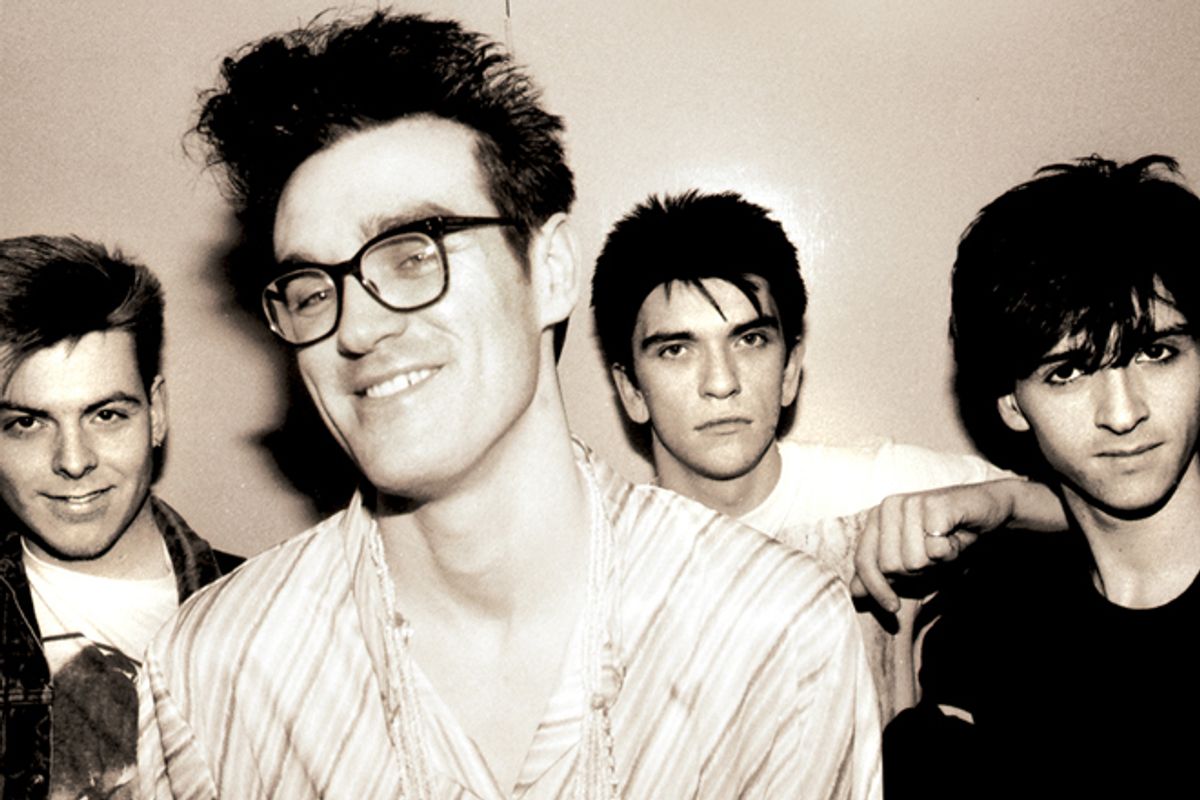

But the legacy and legend of the Smiths only grows. As teenagers in Manchester, England, few would have predicted Steven Patrick Morrissey and Johnny Marr would become the next great British songwriting teams, and one of the very best of all time. Morrissey was most comfortable in his childhood bedroom, firing off biting missives to music magazines; awkward and sexually ambiguous, he seemed neither frontman nor poster boy. Yet one day in 1982, Marr knocked on his door, on a hunch that this 23-year-old misfit might become this charming man.

The partnership that ensued led to arguably the most important music of the decade, and some would say even longer. It's a nearly note-perfect catalog that endures because it sounds like no other, and speaks directly to the vulnerable, romantic heart of all ages. Marr's as an inventive a guitarist of his generation, whether providing the jangle and bounce to "This Charming Man" or "Hand in Glove," the siren squall to "How Soon Is Now?" and "The Queen Is Dead," the cinematic scope of "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me," or the delicate solo to "Shoplifters of the World Unite." And Morrissey's lyrics followed in the tradition of Oscar Wilde and Philip Larkin -- lovelorn, yes, but funny, literate, smart, alive.

The terrific British music writer Tony Fletcher has just published the definitive biography of the group, "A Light That Never Goes Out: The Enduring Saga of The Smiths," taking almost 700 pages to tell the story of just 70 songs and this essential slice of the 1980s.

"Those my own age, most of us parents now, some even with angst-riden teenagers of our own, mostly greeted a mention of the Smiths as if I was speaking of a former lover," he writes. "And it's true: the Smiths helped many an American youth of the 1980s through the growing pains of high school and college in lieu of (and occasionally, for those lucky couples who bonded over the band, in the company of) a boyfriend or girlfriend. Crucially they continue to do so."

Over tea at the W hotel in New York this week, Fletcher discussed where Morrissey and Marr stand, why the partnership splintered, what a fifth album might have sounded like, and crucially, whether the millions of dollars they're offered every year for a reunion tour will ever be accepted.

Let me start with the big legacy question. Morrissey and Marr: Should there be any doubt that this is as significant a songwriting team in rock history? Where do you place them in the pantheon of rock 'n' roll songwriting greats? Is it right after Lennon and McCartney?

I place them right up there. There is a big caveat -- the Smiths did not have the success, during the time they were together, as Jagger/Richards or Lennon/McCartney. They didn't have that in the time they were together. What they did do is turn out 70 songs in just over four years. Seventy songs is a phenomenal outpouring -- and I've been criticized for daring to suggest that just one of them might not be up to par. The amazing thing about the Smiths in general is it doesn't get old. It just seems almost like the longer the time goes on, somehow the fresher the Smiths sound.

So I think when you look commercially, you can't say Morrissey and Marr were on the level then of Lennon/McCartney and Jagger/Richards.

But put aside commercial success. Culturally, weren't they every bit as influential?

Yes. Culturally and for longevity and for credibilty, and words like that, I think you can put them up there. I think the British have gotten into a mind-set where the Smiths are as important as the Beatles. You can't really make that argument; it doesn't hold up in court. What you can say is that for its generation, for the period of music that we went through, for its longevity, for the fact that they're still making movies with these guys and their music is part of the plotline. For the fact that people can't stop talking about them … I think you can say they were damn important, and they are among the greatest of songwriter partnerships we have seen in rock 'n' roll.

There are simply so few bands that engender that kind of love, that pull people through their teenage years, and I imagine they're the soundtrack for as many lovelorn teens now as they were back in the 1980s. They're cherished in a way that it's hard to cherish the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. Their songs might have charted higher and sold more. But they never had a "How Soon Is Now?" with a line like "I am human and I need to be loved / Just like everybody else does," a "There Is a Light That Will Never Go Out" -- songs that made people want to hoist them on their shoulders and carry them about the town. The Smiths knitted together the people who knew them and loved them.

I think you actually put that very well. I'm inclined to agree. I've been asked more than a few times, "Why do we still care about the Smiths? And what's so special about them?" I think the reasons are very closely entwined. One of the great things about the Smiths is that they broke up before they could make a bad record, and also before they got too big to become insiders. In Britain they were massive, but they were still massive outsiders. They were never the flavor of the month with the mainstream. And so, to be a Smiths fan you could align yourself with other Smiths fan, as I am not of the mainstream.

I think it's even deeper than that here. In England, the Smiths had hits and radio play from the beginning. We didn't have John Peel or the BBC, or the NME and Melody Maker putting interesting bands on the cover every week. Rolling Stone probably gave them the polite three or three and a half star reviews in issues with Heart, Billy Idol or Huey Lewis on the cover. You had to work harder, so finding that person with a Smiths shirt was enough for instant friendships. And that's actually how the Smiths began as well: Johnny Marr thought Morrissey might be an ally, and he knocked on his door. The myth has always been that Marr pressed a chocolate-smeared nose against Morrissey's window as he peered inside, but you say he actually brought a friend and knocked properly.

He brought a mutual friend, which is very important.

Because Morrissey was awkward even then: He's 23, five years older than Johnny Marr, and living with his mom, completely unemployed. So why did Marr think Morrissey could be the lyricist in a band?

That's a really good question. It shows either incredible intuition on Johnny Marr's part or it shows a leap of faith that was nonetheless rewarded. Morrissey has been on the Manchester scene really since the early '70s, when he was so infatuated with the New York Dolls that he ran whatever kind of fan club there was in Britain.

He's known around Manchester. He's been writing letters to music magazines forever. They publish them, but he can’t really get a gig as a journalist. He's left school at 16; he's done another year just to take some exams; he's taken jobs at Britain's internal revenue; he’s done another bureaucrat job; he’s worked in a record store for a few weeks; his mom has tried to pack him off to America. Now he’s come home. He’s living in his bedroom. He does have multiple pen pals -- all of whom are somewhat fearful of Morrissey because he is so virulent on paper, then seems so insecure in person. He’s auditioned for a couple of Manchester punk bands when they’ve lost their lead singer. Nothing comes of it. So for someone who is at the first Sex Pistols shows in Manchester, really not much has happened at this point. There is a sense that it might not happen for him.

He is in his 20s and living with mom, after all.

Yes. And Johnny Marr, at this point, is what would appear to be the polar opposite. He’s kind of known about town, he’s kind of Jack the lad – it's an expression we use in Britain. Very, very, very talented guitarist, and he's been honing those skills. Johnny Marr knows everybody, people wanted him to play in their bands. He’s kind of held off of doing that because he wants his own band, but he’s also really not made it happen yet.

Johnny left home at 16, he’s done the opposite of Morrissey. Johnny’s had the same girlfriend since he was 15; he’s going to end up marrying her. He’s got a lot of his life sorted out. But he needs a singer for his group. He has fallen in with a managerial figure, who runs a very successful clothing chain in Manchester. This guy has shown him a documentary on Lieber and Stoller, and basically said to Johnny, “If you think this guy, Morrissey, who you’ve heard so much about, but never met, is the right person – well, this is what Jerry Lieber did. He went and knocked on Mike Stoller’s door."

So Johnny gets dressed up and he gets a mutual acquaintance. He knows that if you knock on Morrissey’s door and Morrissey doesn’t know who you are, he’s not going to answer. He’s going to open the curtain and stay up in his room. They go up unannounced, uninvited – probably better off doing that than calling Morrissey. And there’s a couple of amazing things about this. One amazing thing is that Morrissey actually opened the door and let them in, because that doesn’t seem true to his character. The other amazing thing, though, is this works, instantly.

And a great partnership is born.

I think Johnny thought, there is something about this guy, but maybe he just needs the right partner. If it had not worked out with Morrissey, Johnny Marr would have knocked on someone else’s door.

What would have happened to Morrissey if that knock had never come?

The thing is, it did. When I was talking to Johnny, I raised this point, because Johnny said something like: “I didn’t think Morrissey was particular lonely. I think things have been exaggerated a little bit.” He said he had friends; all of his friends were very interesting. And he said, “I think he was just cultivating his setting." I asked what he thought Morrissey was doing, and John said, "I think he was just waiting for the right person to knock on his door."

How was he supposed to know it would happen? Johnny said, "I don’t know, but it did." This is where we moved into a very existential conversation about what would have happened had the knock not come. But the knock did come. And Morrissey was “discovered” by an 18-year-old and lo and behold off they go and they become the great partnership you just said they are.

Yes – but only after Marr passes a test. Morrissey has a huge collection of singles, and he asks Johnny to play a song. He finds a rare single by the Marvelettes, puts on the B-side, "You're the One," and sings along to every word.

If it was a test, it’s one he passed. I think Johnny thought, “If Morrissey is asking me to play a tune, don’t be too obvious. Play something where you know what you’re playing.” Maybe it was a test. They did have a lot in common, these two: Girl groups, rock 'n' roll, rockabilly, everything coming out of New York, Detroit. Patti Smith --

The knock comes in May 1982. By October, November, they're playing shows. I'm sure you have the same bootlegs I do. They just seemed fully formed from the beginning – "Hand In Glove," "This Charming Man," "What Difference Does It Make?" – they just tumbled out.

Well, the first gig at the Hacienda is on YouTube. It's their third show -- and it is frightening. I make the point that every song in that set, something becomes of it, it ends up on an album or a B-side. You know, the first day of songwriting, they write the songs to close out sides 1 and 2 of their first album ("Suffer Little Children," "The Hand That Rocks the Cradle"). And for a band to have a gig where something becomes of every single song? I mean, that is astonishing. “Hand in Glove” comes early. They got on a roll. “This Charming Man” comes by late summer. The speed at which they work and the speed at which things happen for them -- people have asked the question, “Could the Smiths happen now?” I think something unique to the times was how quickly music could move. You could form a band, and you could do a gig, and you could make a tape and someone could say, “I’ll put it out.” Then John Peel could say, “I’ll give you a session.”

So why were they such a great team?

It breaks down into a couple of reasons. Let’s just allow that individually they were each incredible. Johnny Marr’s musicianship at his age was just astonishing. The fact that he was playing weird chords, the way he played guitar with sort of passing notes. He had a great instinct for layers and what would work in overdubs. And Morrissey had struggled as a poet, had struggled as a correspondent for music papers, struggled as some kind of journalist/author. The pop lyric gave him the freedom to do what he needed to do, and he wrote some of the greatest lyrics of his time. They certainly shared a background: They both came from Irish parents, both their mothers were very young, they were close to their moms, they were both moved out of their working-class areas of Manchester when the slums were torn down and relocated. They’ve got a lot in common.

But they also complemented each other. Morrissey had the design sense and gave the band the visual look, put all of those great movie stars on the sleeves and helped cultivate the band's aesthetic. And since he wasn't a musician, he yielded the studio to Marr.

I think the opposites did attract. Morrissey could sit down and do this interview with you and it’d be amazing -- you’d be in stitches. Johnny would be very happy to be at home with his guitar and four-track tape recorder, knocking out the new songs. Calling up band members, calling up roadies. Morrissey wanted to do the artwork. Johnny was like, “You do it.” They had these very, very clear delineations so they weren’t stepping on each other’s toes.

Even in the studio, there’s an awful lot of respect. Johnny Marr would go to lay down the arrangement, then Morrissey could listen to it, figure out what he wanted to sing, and very often not tell the others -- especially in later days -- what it was until he went in and sang. At the point that he sang, they’d be like, “Oh my God, that’s what you wrote to this.” Which, incidentally, is the way Michael Stipe did it for R.E.M. I think that worked very, very well. They were smart enough to not have desires on each other’s position for a very long time. Later, toward the end of the band, there was an argument to be made that they got a little jealous of each other’s position and that contributed to the disharmony.

Neither of them sounded like anybody else. Nobody sang like Morrissey. The idea that you could sing like Morrissey was probably a pretty outrageous thought, and there’s still nobody like Johnny Marr. So as great a team as they were, it’s not a team that you would have necessarily picked.

I made the point early in the book that the Smiths, like the greatest of bands, you recognize a Smith’s song the moment you hear it. And I do agree with you. It’s one thing to be a talented guitarist -- a heavy metal guitarist can show off all they like, but to me, often, it’s just style. Johnny’s style is all his own. And Morrissey’s style, much as he had influences, he came out with something that was just utterly Morrissey.

How does Morrissey become such an amazing lyricist? Everybody talks Oscar Wilde, Philip Larkin, some of the obvious influences on him. But at that age, to be writing "How Soon Is Now?," to be writing "Reel Around the Fountain," is pretty staggering -- for somebody who never left his mom’s house, to have that kind of insight into the human heart is pretty staggering.

It is pretty staggering, but you have to go back to the fact that he’s spent six years out of school, having the opportunity to -- as Johnny put it -- cultivate his aesthetic. He did go out in Manchester. He did go out to shows. He was something of an observer. He was an observer of the human condition, and he was a smart writer. That was always his skill. His letters, of which there are hundreds flying around, are sometimes quite childish, but are generally quite witty.

I make the point that the first two songs they wrote together, “Hand in Glove” and “Suffer Little Children,” are among the more poetic. They appear to be lyrics that maybe Morrissey had as poems, before meeting Johnny Marr. And he gets into a certain period where a couple of songs push the Oscar Wilde thing maybe a bit too far. But I think the next thing that happens is you get confidence, and everybody knows this, particularly when you’re young: If things go well for you, you have the confidence to try things. So, it doesn’t take Morrissey long before he can write “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now.” It synthesizes the human condition with individual lines that, I feel, we can all identify with.

In "Half a Person" he sings, "Sixteen, clumsy and shy." What do we know about Morrissey at 16? Is that him? Was he the unhappy teen of that song, or the lonely student of "Headmaster Ritual" or "Rusholme Ruffians."

To some degree. He would come down to London and stay in hostels of some kind. He would stay in very cheap hotels, of which there’s no shortage in London. And so I think, to some degree, that was him. But I also think, you know, we are talking about the lyrics. What Morrissey became more clear about -- the first album, I think, was Morrissey. And then Morrissey got into what he needed to do, where you become a narrator. A lyricist, a songwriter -- but don’t start confusing too much the songwriter with the singer. So I think there is always something of Morrissey in these songs, always. But is it all Morrissey? No. He was going out of his way to say, “Don’t always assume that just because I’m singing this it's all my life.” Because he wrote some really romantic songs, but didn’t appear to be much of somebody with a romantic life.

What do we know of Morrissey's romantic life or sexuality? He talked about being celibate for years. Does he have relationships?

I think right now it’s an open secret that he’s gay. He’s had male partners and he’s quite visible with them.

So why won't he say that?

Why did Morrissey not come out earlier in life and why was he so adamant that he not talk about it? I think there were two reasons. One, actually, I think has to do with a certain self-repression. You know, it comes back to living with your mother. There’s a certain amount of Catholic repression going on there. I don’t want to be the armchair psychologist here, but I think it does go back to his mother. The big interview that People magazine did in 1985, the journalist very pointedly quoted Morrissey’s mother saying, “He just needs a nice woman to settle down with.” It might have been a message to say that your mother doesn’t know what the rest of the world knows.

But the other part of it is as poignant and as important, is that Morrissey did not want to be typecast. So although it was OK to be Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Culture Club, we also saw them as very effeminate bands in a certain way. And I think Morrissey really wanted to say: I am what you make of me. I proclaim myself celibate, and therefore I am removing the need for a sexual identity. You can identify me any which way. You can have a female-male crush on me, you can have a male-male crush on me. You can almost have a male-female crush on me if you want! Or you can follow the celibacy thing that I’m projecting, which is: Maybe we’ve overrated all of this.

Part of Morrissey’s personality that I found liberating was growing up in Britain -- and I’m sure it’s true in America -- at 19 years old and you don’t have a girlfriend, people are going to say to you, “What’s wrong with you, mate? You a poof?” And maybe you are, but you can’t come out and say it because you’ll get beaten up. And maybe you aren’t, but it’s just not working out in your life. And maybe you just want someone to say, “It doesn’t matter.” I think that that was a genius element. So whether or not he didn’t have the confidence to come out, I think there was also a sense of, “No, I refuse to let you identify me.”

Let's walk through the albums. They play these amazing songs on John Peel, with Troy Tate – and then the first record feels a little too smooth. I think I prefer the arrangements on "Hatful of Hollow" almost uniformly.

I think the first album was a disappointment for all concerned, including the Smiths. The songs were not in question. The Smiths obviously preferred those arrangements too, because six months later they put out "Hatful of Hollow." They have these brilliant songs. They become the band of 1983, the new band of 1983. They got themselves a hit. But they were up against it time-wise and money-wise. Some of the songs came out brilliantly, I think, particularly, oddly enough, the first two Morrissey and Marr wrote: “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle” and “Suffer Little Children.” Partly because they didn’t get played a lot onstage, I think is part of it. Some of the songs just sounded like their better versions lurking on those Peel Sessions, where you have eight hours to do four songs and minimal overdubs. Knock them out. It was a bit of a mixed bag.

"Meat Is Murder," for me, is an absolute triumph. It’s the moment when the Smiths come of age. They’ve laid out that they’re more than a one-trick pony or one-album act because “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now,” “William It Was Really Nothing,” “Please, Please, Please” and “How Soon Is Now” had proven that they were a band on the rise. That they were here to stay. But for me, when that album arrived, it was a statement, and it was statement of the Smiths as an albums act. Because there are a couple of very long songs on there: “Barbarism” and “Meat Is Murder.” It’s a dark, rainy album. It’s a political album.

And yet, the opening song on that album, “Headmaster Ritual," has got this one-minute intro. It says, "We’re so comfortable with what we’re doing, we won’t even give you the lyrics for a minute. We’re just digging this riff.” And that song is powerful intellectually, it’s a revenge song, it’s something of a pop song, the production is magnificent. So I think that "Meat Is Murder" is in some ways the best indie album of the 1980s.

"The Queen Is Dead" feels completely different: Very imperial, very British, more of a rock album, but also the beautiful, lush orchestration of "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" or "I Know It’s Over."

Yes. And even though some of it’s very acoustic, like “Cemetry Gates,” and not loud like “Vicar in a Tutu,” there’s a certain confidence. “The Queen Is Dead” is an incredible tour de force. That’s been picked up around the U.K. as maybe their greatest recorded moment. None of these albums could have happened without the one that preceded it. On a given day, I think they’re equal, "Meat Is Murder" and "The Queen Is Dead." I think they’re equal as albums, just depending on what mood you’re in. The band have sort of retroactively really said how happy they are with "Strangeways," and I get that. I think there are two reasons that they say it: One is, because they broke up before it came out there is a need to just constantly remind people, “We didn’t know we were going to break up. When we recorded it we honestly didn’t know. We had a whale of a time.” So they say it’s their best album.

It sounds like a breakup album. Maybe that’s because we heard it through those years, but it sounds unhappy. For all the talk of the Smiths being a miserable, depressive band, I always heard the humor – but "Strangeways" feels bitter.

I would give you that. I think the other reason they say it’s their best is they were extremely happy with the production and what they were doing. My take on "Strangeways" is not so much that it’s a breakup album. My thought is that it’s a transitional album. I think they needed to make an album that was experimental in nature, that tried some different things, that got very orchestral, that pushed the boat out. But I don’t think it congeals as an album the way the other three do. I would say, in a way, you’ve got two four-star albums and two five-star albums. And then you have a bunch of five-star singles and you’ve got a pretty healthy career.

They released singles so restlessly: Would the catalog look better if it was seven albums and not as many singles?

No.

Really? If instead of a singles collection like "Louder Than Bombs," if those were two more albums?

I think part of the beauty of the Smiths is that it was chaotic. They were eminently chaotic. They were self-managed. Not so much out of choice, but out of Morrissey’s inability to trust anybody. And they made some bizarre decisions. When "Meat Is Murder" came out they were busy promoting a former B-side, which happened to be their best song ever, “How Soon Is Now?”

But as soon as "Meat Is Murder" came out they recorded "Shakespeare’s Sister" and Rough Trade put it out. The Smiths were operating on a very old-fashioned basis, that you record singles and you release them like sending postcards or letters home. The catalog wouldn’t have looked better -- it wouldn’t have sounded better, because another reason why the Smiths sound so timeless is because some of their recordings are relatively amateur. They weren’t trying to record to the standards of the time. They weren’t trying to say, “What do we need to do to get on the radio? Oh, we need synthesizers and big booming reverb drums.” So I see that the amateurness of all of this actually plays into why the Smiths lasted. Could their career have been more successful had they taken their time with albums and not made daft career decisions? Yes, but I’m not sure they would have been as exciting and I’m not sure we would have been as excited by them all these years later.

We'll never know, but what do you think the next record would have sounded like, had "Strangeways" been a transition album?

Well, this is where we come to talk about the band that we’ve both used as a comparison: R.E.M. "Strangeways" would have been R.E.M.’s "Green." I think "Green" is a record they had to make, but at the time nobody felt, “This is our favorite R.E.M. album.”

But as Peter Buck starts playing other instruments and pulls out the mandolin, you can hear, in retrospect, them working out the ideas that would become "Out of Time" and "Automatic for the People," and make them the biggest band in the world.

You’re absolutely right. So my sense is -- it’s so hypothetical, ultimately -- but my sense is something that could have been more acoustic, that could have been more orchestral, that could have moved away from the rock anthem a little bit more. It could have gone a lot deeper, but as fate had it, Morrissey and Marr’s love affair -- which was a platonic love affair, they had five great years together, which is longer than a lot of intense love affairs -- had run its course, unfortunately. And so it was not to be.

Do they regret not having made that album?

Johnny Marr was insistent -- Johnny was extremely helpful in this process, when I interviewed him it was really two days of very intense interviewing. He was very adamant -- and I pushed him on it -- he said, “Look, the most you’re going to get from me is that we had one more album in us. If I hadn’t blown up, if I hadn’t left when I did. If I had bitten my tongue and not called the NME and said, ‘I quit.’ If they’d been nicer to me -- there was one more album. We were meant to be for that period.”

If you look at it, there were three great British bands in a similar timeframe that broke up and never reformed: the Jam, the Clash and the Smiths. All of them had relatively short careers, and there is definitely a case to be made that once you get to four albums you either have to really raise your game à la R.E.M. or you can get into trouble.

Have either Morrissey or Marr lived up to their potential on their own?

What do you think?

No. I don’t think it’s even close. The Johnny Marr story feels like a great tragedy, like he ought to have a much stronger catalog and influence than he does. He should be the Edge. And Morrissey's solo albums have some tremendous singles and high points, and some are just dreck. He can still put on a terrific show. But he's never had that songwriting partner to push him back to transcendent. And I don’t think that’s just the hopeless teenage romantic in me talking.

It’s not. And I am not going to speak ill of them for their choices. I think that Johnny was so bruised by the Smiths experience that he could not commit himself to another band to that degree. Because he should have been, by your view and mine, Johnny should have partnered up in another act where he could have been 50 percent and he would have been as important as he was to the Smiths. And I guess that the prevailing opinion is that the Smiths hurt him so much that he was scared to do that.

So it becomes an album with The The, a partnership with Electronic, a stint in Modest Mouse.

He will say, “That’s what I was born for. I'm born to have this two- or three-year interest and then move on.”

But I think with Morrissey it was a different story. He carried on with what he was doing and decided not to change. So to Johnny’s great credit -- Electronic, their first album I thought was superb. It was a 180 degree about-turn from the Smiths. Johnny knew there was something more exciting in Britain and he wanted to be a part of it. Morrissey kept on singing in a very 1960s way, and in that way he never changed. Morrissey is Morrissey is Morrissey. Johnny is the one who decided to try this, try that, try the other.

Morrissey had it harder because he’s being compared to the Smiths. There is a quote from Morrissey in the book and it is a tear-jerker. “The Smiths had the best of Johnny and me.” And that’s very, very sad -- but I think he recognizes those were the best years of his life. And you can well up on that one. If you get back to Johnny knocking on Morrissey’s door -- lightning strikes generally once in your life. They’re both very fortunate to have carried on with very successful careers.

They deny that they’ll ever play together again fairly vehemently, but the rumors don’t stop. The offers just go up. Are they serious? Will this reunion ever happen?

I think they’re serious, and I think it would be a great mistake to come back. I really, really, really do.

But everybody does eventually. With the exception of maybe the Jam.

I could possibly, possibly foresee a day when Marr might just walk on Morrissey’s stage. That’s about as much as I can see, because I think they’re both smart enough that they know that legacy is pure. I think, you know, give musicians some credit: The ones who have made some money -- and Morrissey and Marr have gotten the rights back to their recordings, they pretty much own their publishing. There is a limit to how much money you need, regardless of what the Rolling Stones think. And I think that they are pure enough to know, “When I die I want to have left that legacy of the Smiths. I don’t want to have fucked it up by doing some half-assed reunion that just goes and completely messes up people’s memories of us.” You know, Fat Morrissey. I don’t see it happening because I don’t think the relationships are there.

That was my next question. They remastered the catalog last year and must have communicated on that. Yet there've also been court cases around money that's owed and a lot of anger on both sides. Is there any communications between the four of them?

Not as the four members.

Between Morrissey and Marr?

Morrissey and Marr have been in touch because they co-own all the material, so I believe they’re in contact.

Are they friendly?

(smiles) You would have to ask them. Andy Rourke is in contact with Johnny and Mike Joyce, he’s very good friends with Johnny and Mike. Last I heard from Andy he was going to be suing Morrissey for nonpayment of what little money he’s ever meant to get from the Smiths. You know, I think Andy had signed off on getting 10 percent but doesn’t get his 10 percent. He actually told me I can quote him on that, so I am quoting him on it. There’s years going by waiting to get paid. Mike still hasn’t straightened out the court case with Morrissey, and Johnny has a big problem with Mike because of the court case and how it was handled. So only Andy is in contact with more than one member on a regular basis.

A reunion is not going to happen. I think they’re all upset by it. Johnny’s great disappointment is that, “We did all this and it was magic and we broke up and since then it’s all been fucked up.” And that hurts. I think that hurts all of them. How come it was so great when they were together and now it’s so bad?

And so I don’t see them reforming. I think they each have their separate paths in life.

Shares