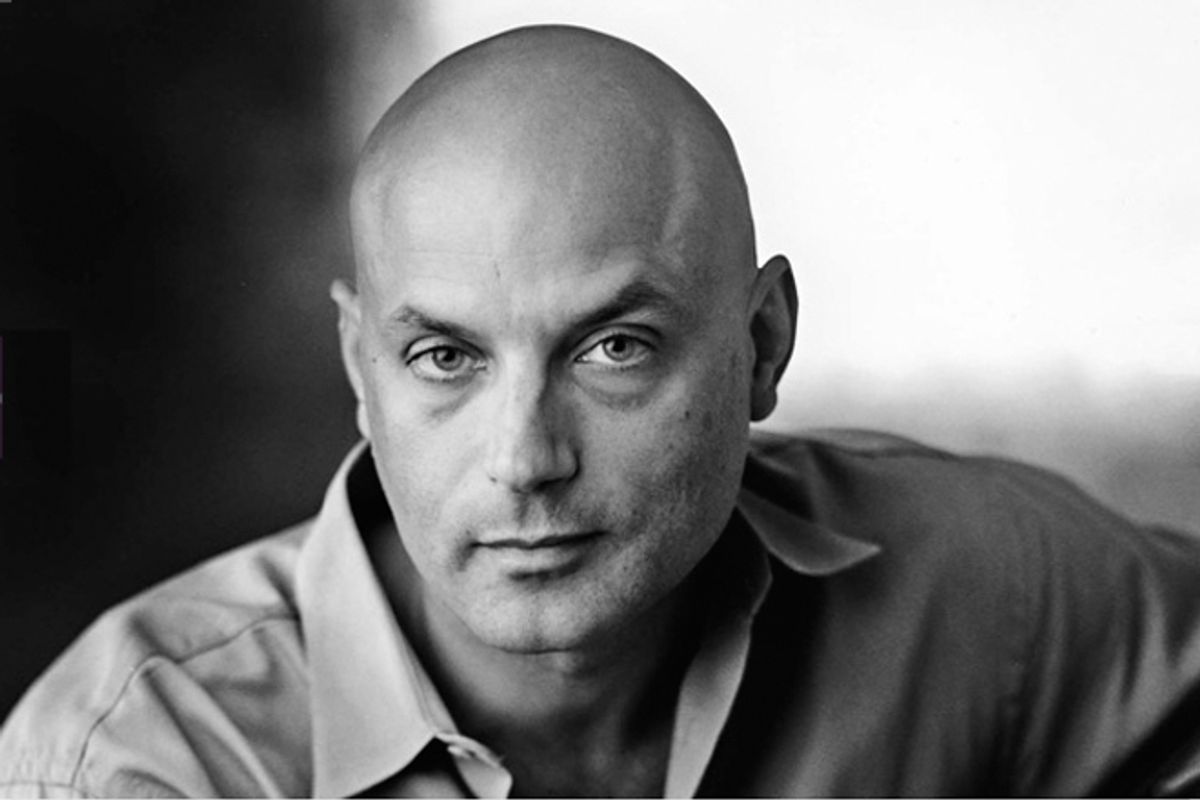

"Waiting for the Barbarians," Daniel Mendelsohn's new collection of criticism (much of it originally published in the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker), testifies to the author's wide-ranging and omnivorous tastes. With his background as a classicist and his track record as a one-time weekly reviewer for New York magazine, he's as authoritative (and as happy) writing about Herodotus and "Avatar," pop culture's fascination with the Titanic and Susan Sontag, Noël Coward and Jonathan Franzen. There could be no better partner for a conversation about the surprisingly tumultuous arguments about the state of book reviewing in 2012.

Our theme is the year in criticism, and there's plenty to talk about, but first I have to express my astonishment over what we didn't see this year: I can't recall any memoir being exposed as partly or wholly fictional!

I know! It's very disappointing. There was a while there when it seemed like every time you opened a newspaper there was a new one. There was the girl in L.A. who said she grew up in a gang when she really went to a prep school, and the lady who fled the Nazis and went running with the wolves. I've decided that the phony memoir is my favorite genre.

You write in the preface of your new collection that "the reality problem is the preeminent cultural event of our day," and you've written memoir yourself, so that doesn't really surprise me. But tell me what you like about phony memoirs.

All kidding aside, they're interesting because the reaction to them when the shit hits the fan tells you a lot about our expectations of the genre. They're revealing about us and what we want. What does it mean to be truthful in a memoir? Why do people attach so strongly to memoirs? When the memoir's basis in truth is called into question, can they still get something out of it? The James Frey thing was a perfect example of that.

Because some people said that even if "A Million Little Pieces" was partly fabricated, they still found the book an inspirational account of addiction and recovery?

Right. But I say, fine: Then it's a novel. What you want to get from a novel is different from what you want from a memoir. When you find out that some extraordinary story in a memoir is not true, it does alter your sense of the book in a very particular way.

People want real life to be amazing. We're creatures of narrative. That's how we make sense of the world. And stories are aesthetic, from the start. We want our experience to be a story, to have a beginning, a middle and an end. What we love in memoir is when life seems to conform to that aesthetic template. And therefore, the great disappointment when it turns out that the facts have been manipulated to be more like a literary narrative. The memoir's traction is: Can you believe that someone's actual experience is so much like a story?

You quote William Dean Howells in the memoir piece that you wrote for the New Yorker, and it reminded me of something I wrote earlier this year. He said that what Americans want is "a tragedy with a happy ending." I think that a good part of this comes from the belief that it's the job of the books we read, whether fiction or narrative nonfiction, to cheer us up, to inspire us. And I do think that is particularly American, the idea that literature has this self-help function. People want to be told by someone, "Even though I seemed to be living a tragedy, I had a happy ending." And by implication, you can, too.

This is deeply embedded in the memoir, going back to St. Augustine. I was lost and then I was found. But I do agree that this seems like a particularly American strain, the need for optimism. We are an optimistic civilization. That's what we were founded on, turning European tragedy into American comedy, essentially. We do want things to have uplift in a way that I don't think European readers on the whole do. That's my sense. Another way you see this is when Americans remake European films and TV series. They always have happier endings where everything gets fixed.

We should really move on to the form of phoniness that did command the attention of the book world in 2012, which is the sudden awareness of just how many bogus "reader reviews" there are out there, especially on Amazon. We had academics like Orlando Figes assuming false identities, not just to praise his own books but to pan books written by authors he perceived as his rivals. And we had revelations in the New York Times that some authors, particularly a very prominently successful self-published author, John Locke, had boosted his sales by hiring a service to pad his Amazon page with fake positive reviews.

Then there was Stephen Leather, a thriller author in the U.K., who announced in a public forum that he had created multiple sock puppet identities across a whole range of social media, all for the purpose of touting his own books. His position was that every other author in his genre does the same thing! Of course shenanigans like these have been going on for a while, but 2012 did seem to be the year that the general reading public became much more aware of how un-genuine many of these "regular person" reviews are.

First of all, you have to wonder who these authors are who have the time to do all this stuff. But what's really at the base of this question is the sense that the writer has of his or her presence in the world of letters has radically shifted in the past 20 years. How did you used to know how you, an author, were doing? You had reviews and you had sales and that was about it. That has obviously changed. Besides Amazon, you have Twitter, your Facebook page. You're constantly bombarded with data about how you're doing. It's a huge distraction.

Speaking of Twitter, over the summer there was a piece in Slate by Jacob Silverman, in which he complained that the literary conversation in social media was too nice.

I have to say, that struck me as a snow-globe argument. In order to perceive the "problem" at all, you'd have to be either Facebook friends with a bunch of authors or following them on Twitter. I just don't think that many people do that.

I understand the complaint, which is that there is this cheerleading. Personally, I view Twitter and my Facebook fan page and all that as primarily publicity media. I tweet when I have events or readings, though I do slide in and out of posting other things. Twitter cannot be discursive. It's aphoristic and epigrammatic, which is genuinely interesting. Oscar Wilde would have been a fabulous tweeter. But you cannot make an argument in a tweet. You can't unfold a thought. So it's inevitably reduced to a kind of cheerleading: "Oh, I love so-and-so's new book!" or "My book is coming out in two weeks."

I'd add that whenever I've wanted to quarrel with someone or someone's wanted to quarrel with me and it's happening on Twitter, it never works. The medium doesn't support thoughtful disagreement, so the result tends to be that someone gets offended. It's an absurd place to look for literary criticism.

Certainly Facebook replicates that in another way, because everyone is "friends." I'm waiting for the day when you can have enemies on Facebook -- that's when it'll get interesting. It's only possible on Facebook to like things, applaud things, cheer people on. I understand his point, but as with Amazon, it's is only valid if you give a shit about that stuff. Nobody really thinks that these are venues for serious criticism. It doesn't represent the literary culture, it's just one aspect of literary culture -- one of the ways people exchange information about books, reviews, reviewers. It's not the entirety of that.

I think he's mistaking a conversation among colleagues — novelists who know each other from readings or workshops or retreats and who feel a collegial desire to support each other — for a greater public conversation about books. That sort of banter is not meant to be on the level of a published review or essay. I suspect the people who do it see it as more like turning out for a fellow writer's book party or recommending a friend's book on a year-end survey. Authors get dealt enough insults in the course of everyday public life, it seems churlish to begrudge them these really very tiny social media circles where they support each other. They've always done that, it's just that now some outsiders they don't actually know …

… are privy to it, yes. I'm old-fashioned enough to think that the only thing that matters is what your publisher and editor says about the book. All of the rest is to my mind a kind of noise. When you're a writer, you're alone. It's a solitary activity. You can hold someone's hand up to the cliff, but they always have to go over the cliff alone. That's what we spend our days doing. I do have to wonder if the rise of social media is creating a desire in young writers for a constant stream of affirmation. This is part of this whole larger trend in which we're living more and more of our private life out in public.

Another form that takes is the author's response to a bad review. Before, you might complain about it with your friends on the phone or over coffee. Now, that sort of angst often gets expressed on Facebook or Twitter. Or a writer's friends will take up the cause in those forums and drop sinister remarks about the reviewer's ulterior "agenda."

They always say that! Of course, if you're talking about a professional assignment, no good editor would allow that to happen. I don't think it's Pollyanna-ish or naive to say that if you were given an assignment and you had some personal gripe against the author, you would recuse yourself. I've done that. But people always instantly assume that you had it in for that person when you've written a negative review. It's a pernicious myth. Of course, we do have agendas that are aesthetic. That's different. That's a legitimate agenda.

People also have the idea, especially if you're not liking something very popular, that you've been gunning for it the whole time. In my experience, that's never the case. You always go to a movie or open a book hoping that you're going to like it. You don't say, "Oh, everyone loves 'Mad Men,' so I'm going to knock it down!" Because why would you put yourself through that? This is actual work. I don't want to sit through something I hate, knowing that I'm going to have to criticize it strongly. You always start out with an open mind.

In my experience, authors and people who work in publishing get these notions because they tend to think of book reviews as a service that the publication provides to them. When they aren't getting what they need, then as far as they're concerned, something has gone terribly wrong and has to be explained. The editor, on the other hand, is only thinking, "How can I get a good, interesting piece?" They don't care about how it's going to affect the writer's feelings or career. That's not their job, and it's not even of much interest to them.

The review is for the readers.

Exactly. And here we're segueing into a conversation about the biggest debate in criticism this year, which was about William Giraldi's review of Alix Ohlin's novel, "Inside," in the New York Times Book Review.

Also Ron Powers' review of Dale Peck's novel, "The Garden of Lost and Found." One of the things that came up in the conversation about both of those flamboyantly negative reviews is accusations that they were personal or "ad hominem." Those were not in fact ad hominem reviews. They were legitimate. They were strong, maybe even over the top, but I don't think people even know what "ad hominem" actually means. They just sort of think it's anything harsh. There are certainly things that are off-limits in reviews, but not liking something very strongly is not one of them.

When it comes to the Alix Ohlin review, we're talking about a fairly obscure literary novel. With that, I came down in an in-between place. There was a certain contingent that felt that the review was excessively crushing and hurtful to the author, which, with all due respect, the author's feelings are not an issue any reviewer should be taking into consideration. Again, book reviews are not a service provide to authors (or publishers). They are for readers. Then there were people who felt he was applying a useful scourge to a too-indulgent literary community.

For me, as a reader, coming across that review was like opening up the New York Times dining section and finding a savage review of a Thai restaurant in a strip mall in Lincoln, Nebraska. By all means, tell me about the Thai restaurant in Lincoln if it's sensational, although chances are that, living halfway across the country, I'll never get the chance to try it, but why devote all this space and energy to excoriating something I'd never otherwise be aware of? Maybe I believe you that this the worst Thai restaurant in America, but is there a good reason to point it out to me at such length? Part of the critical process -- a very active part -- is simply deciding that something is not worth reviewing in the first place.

More times than I can remember, I've turned down, particularly, first novels that I really didn't like. But one of the things that affects your decision to review something is its pretensions. If everyone is saying this is the greatest thing since the Gutenberg Bible, then I think a sterner review has a salutary function in the culture overall. Or it's something you know a lot about and you think the writer has gone totally off track, like this novel I reviewed earlier this year, based on the Iliad. As a classicist I had something useful to say to readers about that, even though I didn't like much of it. My friend Bob Gottlieb always says that criticism is a service industry, and my expertise in that area is a service I can provide to readers.

That book, "The Song of Achilles" by Madeline Miller, was, I would argue, a major release with a lot of advance praise that the publisher was heavily promoting. I think books like that are always fair game, because your readers are likely to hear about them and be persuaded to read it.

It's a case-by-case basis. One interesting thing that came out during all the soul searching over these reviews was this idea that you could establish some universal rule about whether there ought to be negative reviews. It's so idiotic. You can't just decide you're only going to publish positive reviews -- that's like the worst aspect of Facebook, where you can only like things.

We both grew up reading Pauline Kael or Edmund Wilson or whatever it was we were reading, and that's how you learn to think. People make strong arguments and you are either persuaded by them or you fight back. I would say you get more out of reading reviews you disagree with because it forces you to sharpen your own thoughts. Even though I was only 16, a certain point, I was reading Kael promoting the movies of Brian de Palma as if they were the greatest thing, and I told myself, "She's wrong!" And that was a great thing, because you can't just say she's crazy. You have to make an argument, push back.

But that type of productive disagreement is founded on shared knowledge of the material. You had to see those Brian de Palma movies to push back. Giraldi was lambasting a novel no one was going to read to begin with, and you'll notice that no one is actually discussing his criteria for literary excellence and its merits, or explaining by what other, better criteria Ohlin's book might be seen as worthwhile. We're just talking about how "mean" he's entitled to be. His defenders go on about the evidence he presented in the form of quotes, but I don't know how much I credit that. You can produce endless quotes to "prove" that Theodore Dreiser is a bad writer, but that doesn't really diminish the power of "Sister Carrie."

My best example of that phenomenon is George Eliot, the greatest novelist who's a lousy writer, sentence by sentence.

When you're registering your reservations about something very prominent -- the way you did in your essay on "Mad Men" -- often the people who share those reservations are intensely grateful to see someone else articulate them, because they've heard all the praise, seen it and disagreed.

Giraldi's defenders seem to be operating under the delusion that literary fiction has the same cultural centrality as "Mad Men." It's this antique idea that the literary critic is the champion of some sort of literary Valhalla, that a certain select number of novels is being published every year and that everyone is reading them, and debating which will get in. Something crappy might get through! But for most people, literary fiction is so marginal that if you're not going to tell them "This is worth reading," they don't really care. Because they're sure not going to be reading it unless they hear that it's really good.

I get your point, and I'm not trying to fudge when I say, again, it's a case-by-case thing. You're right, this is not something most people care about and if we agree that criticism is a service industry, how are you going to serve your reader? You bring things of note to their attention. I just don't think there are any rules. Mostly, it boils down to my belief that criticism is not an ancillary or parasitic activity. It's an interesting genre worth being read in its own right. It's mentally stimulating and intellectually rich. When you read good criticism, it enhances your own critical faculties.

Shares