Israeli filmmaker Dror Moreh got his start making TV commercials for Ariel Sharon, the war hero who served as Israel’s prime minister from 2001 to 2006, when he suffered a devastating stroke that has left him in a “persistent vegetative state” ever since. (Just last week, however, Sharon underwent a high-tech FMRI exam that revealed “significant” brain activity, suggesting that he may be aware of his surroundings.) That’s important background for Moreh’s Oscar-nominated documentary “The Gatekeepers” in various ways.

For one thing, Moreh gained access to six former heads of the Shin Bet, Israel’s secretive internal security service – who had never before given public interviews – largely because of his political connections. Those men had all worked with Sharon and respected him. For another, understanding the political evolution of Ariel Sharon sheds some light on Moreh, whom I met a few days ago in New York, and also on the surprising pragmatism and moral complexity reflected in his interviews with the Shin Bet leaders.

Sharon was famous for fighting and winning several Israeli-Arab wars from the 1940s to the 1980s, and was a longtime member of the right-wing Likud party, which supported the building of Jewish settlements in the territories occupied by Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967. But by the time of his near-fatal stroke, Sharon had come to see the Israeli-Palestinian question in less ideological terms, as a poisonous issue that threatened the Jewish state’s long-term existence. He made the unilateral decision to withdraw from the Gaza Strip (destroying all settlements there in the process), left the Likud in a split with his longtime rival Benjamin Netanyahu, and in 2006 was about to embark – or so many observers believe – on an ambitious program of negotiation and withdrawal designed to turn the elusive “two-state solution” into reality.

All of that now falls into the category of what might have been. But the grandstanding and insincerity of the current Netanyahu government – which clearly views a negotiated settlement of the Palestinian problem as undesirable, impossible or both – stands in sharp contrast to the pragmatic and philosophical outlook expressed by Moreh’s interviewees in “The Gatekeepers.” These men have spent their professional lives trying to understand and combat terrorism – and not always or exclusively Arab terrorism. Former 1980s Shin Bet head Avraham Shalom, perhaps the strangest and most hypnotic figure in the film, once uncovered a right-wing Jewish underground that planned to blow up Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, one of the holiest shrines in Islam. (As he correctly observes, the worldwide anti-Israeli backlash would have been catastrophic.) And the Shin Bet’s largest single failing, by far, was its failure to predict or stop the 1995 assassination of Yitzhak Rabin by an enraged Zionist.

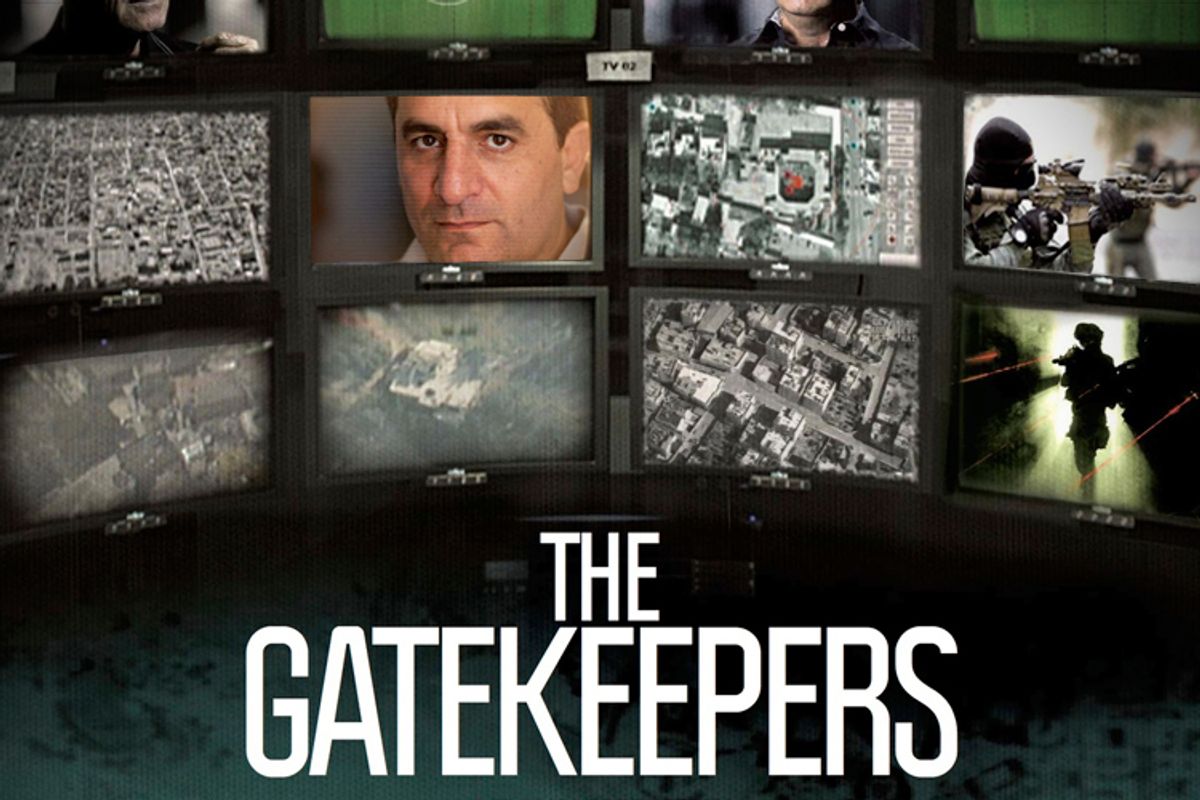

A brooding, ominous and endlessly fascinating exploration of the hidden history of our age and the hidden costs of power, “The Gatekeepers” is a quiet but unforgettable work of cinema, interspersing its talking-head interviews with fragments of newsreel footage and innovative animations that turn two-dimensional photographs into three-dimensional landscapes. Several of these come from the “Bus 300 incident” in 1984, an Abu Ghraib-type scandal in which it was revealed that Shin Bet members had apparently beaten two Palestinian hijackers to death after they had surrendered. That led to reforms within the institution and a degree of moral soul-searching within Israeli society that Americans, I’m sorry to say, seem incapable of emulating. Moreh says he was inspired by Errol Morris’ interviews with Vietnam-era Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in the Oscar-winning “Fog of War,” which is a great film and all – but it took 30 years for McNamara to come clean with his misgivings.

Meanwhile, even as Shalom advises Moreh to “forget morality” when dealing with terrorists, he also says that Israel can no longer afford not to negotiate with any and all adversaries, including Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad and even the Iranian government (if they’re willing to talk, which doesn’t seem likely in all cases). Shalom does not deny having ordered those two young Palestinians murdered after the Bus 300 hijacking – it was a mercy killing, in his version – but in the film’s most explosive moment, he says that Israeli troops in the Palestinian territories have been put in a similar position to the Nazi soldiers who once occupied Europe. This is a man, by the way, who was born in Austria and once saw Hitler speak at a public rally. Then Shalom pauses and blinks, in his phlegmatic Yoda manner, and clarifies a little: He didn’t say it was exactly the same. Only similar.

I met Dror Moreh in a Manhattan hotel bar on a sleety afternoon. We had several cups of tea and a long conversation; he blew off his next interviewer so we could keep going. Trust me, I've cut out a lot that was really interesting, including his extended encomiums to both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton (he'd happily take either as Israeli prime minister).

How are people in Israel reacting to what’s going on in Egypt right now, and the sense that the new Egyptian government really is not stable? I can’t figure it out, personally.

I can tell you that Yuval Diskin, the head of the Shin Bet -- I did a long interview with him prior to the elections in Israel, and he said to me that he really adores the people in Tahrir Square because they are willing to pay a dear price for their convictions, and they are not willing to bend over. You know, they paid a dear price to get rid of Mubarak and they are not willing to trade that. You see that there is something there, which is vibrant. I don’t know how it will end but it’s definitely a source of inspiration. Hopefully the Iranian people will pick up on that as well.

One of the things that’s interesting about your film is the sense that these guys, who have spent their entire lives on one side of the Israeli-Arab conflict, have a pretty nuanced and complicated view in general.

Yes, exactly, they understand exactly what it means to be on the ground, they understand exactly how much force can get you, they understand exactly how much can you give, they understand exactly what they think is the best for the state of Israel. It’s not something that is embedded in right or wrong. It’s being pragmatic. And it’s something that we lack in the political arena in Israel. Being pragmatic, not going wherever the wind blows. Which is definitely what the current Israeli administration is very good at.

This may be a cliché about people who work in intelligence, but to do what they do they have to understand the other side pretty well, right? You don’t just have to understand the other side’s tactics or strategy, you have to understand their philosophy as well.

Yes, coming from their point of view. The source of inspiration for me, for that movie, was “The Fog of War.” When I saw that movie I was completely blown away by it. The morals or the lessons that Robert McNamara gives there are something that definitely a leader should look to, and one of the first lessons there is “Try to see the other side’s point of view.” He was speaking about Khrushchev and Kennedy. In terms of the missile crisis. The hard-liners told Kennedy, ”You have to attack,” and the ambassador said to Kennedy, “No. You need to give Khrushchev a ladder to go down.” And look, at the end of that instance, the world was this close to a nuclear holocaust. With "The Gatekeepers,” yes, they are pragmatic, they don’t follow these messianic issues that political leaders pursue on both sides. Whether that’s Yasser Arafat saying, “I will never give up Jerusalem,” or Netanyahu and his messianic quest, whatever that is.

Are they presuming that everybody, even the most implacable enemy, whether that’s Hamas, or Islamic Jihad or the Iranian regime, is a rational actor? Like they want something, they are not just crazy people who want to blow up the world.

You have to speak. I don’t know if they think that they are rational but you have to speak. When you speak, things get clarified. The old man [Avraham Shalom] said that very eloquently, “I see that you don’t drink petrol, you see that I don’t eat glass.” If the Iranians say, “OK, we want to speak with the Israelis,” I think we should jump on that. Also Hamas – and, by the way, Israel is negotiating with Hamas without admitting of doing that. The last war in Gaza, what happened there? With whom did the Israelis reach an agreement? They reached it with Hamas. Netanyahu tries to play tough, but he has negotiated with Hamas most. Only with Abu Mazen [aka Mahmoud Abbas, chairman of the PLO], by the way, he doesn’t negotiate. Abu Mazen says, “I will recognize Israel’s right to exist, I will recognize the 1967 borders,” but he doesn’t speak to him.

Well, so there is a degree of realism there. Ultimately Israel has to negotiate with its enemies.

With whom are you going to make peace? Are you going to make peace with friends? At the end of the day, as Yuval Diskin says in the film, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” When you reach that point when you see and understand that … the problem, from my point of view, is that sadly Israel only responds to power. That’s definitely true of Netanyahu. I can give you numerous examples of how he has responded to power. When there is silence, when the circumstances exist for creating a dialogue, they don’t do that, they wait. And then when the violence breaks out, then they cannot wait to go to the negotiation table.

When Israel withdrew from Lebanon in 2000, the Palestinian officials were saying to the Israelis, to the Shin Bet: “We gave you security for three years. We fought Hamas, we put them in prison, and we didn’t get anything from you, nothing. You didn’t even move an inch. Netanyahu didn’t move an inch. In Lebanon, Hezbollah hunted and killed your soldiers, year after year, and what did you do? You unilaterally went back to the 1967 borders, with precise measurements. What is the message that any Palestinian gets from that? It’s a very clear and open message: Kill Israelis and you’ll get what you want.”

So from that point of view, terrorists are behaving rationally if they blow up buses in Tel Aviv. You and I may think it’s an atrocious act -- but does it get them what they want?

I don't know. I cannot say that, you know, when you ask me a question like that it gives me the creeps, because I was there. I experienced that firsthand. I was at a suicide attack in the Dizengoff Center, on Purim, our Halloween. I was 100 meters from there and saw chidren -- 13, 14, 15, 16 -- blown away to smithereens, to pieces. I remember 2000, the second Intifada, when I was afraid to go to the cinema, to stand in a crowd, because suicide attacks were swarming all over Israel. It's horrible, at the end of the day, yes, people do that, but there are consequences to that on the ground and it's horrible. I don't even want to think about that period of my life. I remember going into the streets of Jerusalem during the second Intifada, and it was completely empty at 8 o'clock in the evening. So I cannot agree to those words that you said.

At the end of the day the suicide attacks, I think, injured the Palestinians much more than they injured the Israelis. Because they lost everything completely from that. This is the chapter of my film which is called “Victory to us is to see you suffer." Where you see two societies that are trapped, and the only solution they can see is to force pain on the other side.

Summarize for me the importance of the Bus 300 incident, in which two Palestinian prisoners were killed, apparently by the Shin Bet. Most Americans probably won't know anything about it. Why was that so important in the history of Shin Bet and period of Palestinian-Israeli relations?

Because it was the first time. Up until the 300 bus, the Shin Bet was an organization that lived in the shadows completely and did whatever it needed to in order to maintain the security of Israel. That included torturing people and killing people without a trial. Shalom had that authority from the prime minister. And that picture, which is in the movie, of the two officers taking away this very, very alive terrorist, shook completely the Israeli establishment. Because it showed for the first time that the Shin Bet had the authority to order the execution of a captured terrorist. And this incident sent a shockwave through the corridors of powers in Israel. The Supreme Court, the judicial system, politicians, the prime minister. Completely, completely, you cannot even imagine. The prime ministers. And in the movie, it's only, you know, a few minutes. On Israeli televisions there was a six-hour series about this affair of bus 300 because the politicians, mainly Shimon Peres, Yitzhak Shamir and Rabin, by the way, were committed to save Shalom [from prosecution]. Why? Because they knew that if he would get to court it would be their skin on the line, because they gave him permission to do what he did.

It's impossible for me to gauge whether you think Shalom is telling the truth now about what really happened. He doesn’t have any incentive to lie, I suppose – it’s all ancient history. But that doesn't necessarily mean he is telling the truth. Because he is pretty vague: He never saw the two guys personally, he doesn’t exactly know what happened to them, maybe they were dead already when his men got hold of them.

I don’t know, I can’t tell you. There are people who say he saw them, but it’s out in the open now. If it was a lie, there were a lot of people on the ground, so someone would have said, “He is lying, he saw them, he beat them.” But nobody came up until now. Look, he is a very, very smart guy. What I felt was that he didn’t lie.

You know, I think Americans are so funny about this stuff. There has been tremendous debate about “Zero Dark Thirty,” and does it or does it not justify torture – but not much discussion about the inarguable fact that we tortured many people, whether or not it worked. For all we know, Americans do things just as bad as the 300 Bus episode every day, and we just don’t hear about it. I mean, I know that we’ve blown up entire villages in Afghanistan, either by accident or on purpose. Entire families get wiped out and maybe one of them was a terrorist or maybe not. I certainly don’t know which and nobody really notices.

Avi Dichter talks about that in the movie: “You blew up a wedding, 70 people died and nobody knows if the perpetrator was there.” The meaning of that, to any American, 70 people -- everybody who hears that has to think about 70 people that he knows personally, and who died on the ground because of a mistake. That’s the meaning of that.

For all the good and valid reasons that I might want to criticize Israel, I think your country has a stronger moral compass than we do. We are conducting these wars with drones from thousands of miles away, and almost no one ever knows about it. A village in Afghanistan gets blown up and nobody really knows or cares. But Israel actually did care about these guys, who presumably were terrorists. People still felt that it wasn’t OK to beat them to death after they had surrendered.

Yes, there is a big difference. The difference is that they said, “We surrender,” and when you see the pictures you understand that they are alive. Morally, you cannot do that, although when I asked Shalom about morality he said: “When you fight terror don’t look for morality.” But in the case of the one-ton bomb that kills innocent people, then he said: “It cannot be moral, it cannot be justified because there is collateral damage.” I understand that he needed to justify what he did there, although I think that he knows that he made a mistake then, absolutely. And there is the debate between me and him in the movie about what is morality.

It seems like it’s a moving target for him, maybe.

He was very angry with me after that. Believe me, I have interviewed Condoleezza Rice, Joschka Fischer and Arik Sharon, and this was one of the toughest interviews I did in my whole life. I finished it completely sweating. The clash was much harsher and stronger than what is shown in the movie.

His story is so remarkable. I read the things you explained to another journalist about the fact that he was born in Austria and lived through Kristallnacht …

Not only that, he went to see Hitler in the square in the unification after the Anschluss, and one of his cousins was taken to a concentration camp. It was not yet the Final Solution, but the Germans already had camps for the Jews. So yes, he experienced that firsthand. He knows.

So when he makes the comment comparing Israeli troops to German troops toward the end of the film, it’s even more devastating than people realize.

For me it was a shock. I thought, “Shall I put it? Should I?” As a filmmaker there is a goal, and I didn’t want to antagonize people. Because the Holocaust is a very sensitive issue, for Jews definitely. But when I thought to myself, “Shall I put it in the movie or shall I take it out?” I had to put it in. I couldn’t take it out.

One of the painful things that I took out of the movie which will be on television is the relationship with the Holocaust. How do we as a nation, as a society, as the prime minister and the politicians, use the Holocaust, which is in our collective memory, in order to prevent moving forward towards peace? Because they say -- and Netanyahu is the master of that Holocaust comparison: “We cannot go to the Auschwitz lines, it will mean that we will be exterminated like the Jews of Europe, the Iranian bomb is the next holocaust of Israel. I mean this is completely and utterly bullshit, using that in reference of that. It’s two completely different worlds. And we as a society, the Israelis, we have to overcome that conflict -- I don’t know how to call it in English, this things that sits on you all the time: “Everybody want to kill you,” “Everybody wants to exterminate you.” It provides a society that is under siege all the time, in a jungle, and this is a poor, poor future for the society. If you are all the time in a jungle, you will act accordingly.

It’s been striking over the last couple of years to hear various people suggesting that a two-state solution is no longer possible. What is chilling, arguably, is to hear people on the Israeli right and the international left saying different version of the same thing: It’s too late for that, so we have to find something else.

I am much bleaker than the gatekeepers. Honestly, I don’t think that … Israel has gone past the point of no return in my point of view, especially by the settlements. The amount of settlers and extreme right-wingers in Israel is something that I don’t see any leader can cope with, dealing with what needs to be done to create this kind of two-state solution. All the time the heads of the Shin Bet are trying to encourage me. They tell me, “Dror, you are a pessimist. If the right leadership would come then something could happen.” When I ask them, “Well, do you see a good leadership in the horizon?” they don’t see it. But the fact that the prime minister of Israel continues to build the settlements in the West Bank -- this is the biggest obstacle to peace.

The more they build, the less real estate there is to build a Palestinian state from, right?

Or the more you will have to ruin in order to build a viable Palestinian state. I’m not saying that the two-state solution is something that is possible, by the way, but I think that we should strive for that as hard as we can and as seriously as we can. Because, what I feel is that both sides are playing like in a kindergarten. Everybody blames the other side, and is not serious enough to say, “OK, this is what we need to do and how we will move towards that.”

We need Obama to be the kindergarten caretaker, to put those two small stupid kids together and stand there with, I would say, a 20-ton iron fist in one hand, and a 20-ton carrot on the other hand and tell them: This is the deal. Everybody knows how it will end. Ask Netanyahu, he will know how it will end. Ask Abu Mazen, he will know. Everybody knows how it will end, basically very similar to what Bill Clinton suggested in 2000. This is the way; the only thing is how much those stupid kids will continue to fight over that. So he has to come up with the plan, saying, this is it. Take it or leave it. If you take it, do you see this big carrot? This is what you will get, if you take this thing. We will be there for you, for the Israelis in their fear for security, for the Palestinians and whatever fear they will have, we will be there. The United States and all of the international community will be there helping you getting through this transition period, which will be very, very hard. We will support you. And if you don’t do that, you see this iron fist? It weighs two tons, 200 tons, 200 megatons, and it’s going to land on your head. Both of you. With all of the ramifications of that.

What the Israeli right wing, and for that matter the American right wing, both want, which is to keep pushing further into the Territories, to keep building more and more and more settlements – doesn’t that strategy ultimately endanger the survival of Israel?

Absolutely. The biggest threat to the existence of the state of Israel is those on the extreme right wing in Israel and in America, including the evangelical Christians who think, you know, that by law God gave the Jews the state of Israel.

Of course, all those Christians they think that the Jews are going to hell anyway.

Yeah, rather probably sooner than later. But, the main issue is -- look at the history. The history of the Jewish people. Always in the history, those extreme religious fanatics caused the destruction of Israel. Israel was not a country for 2,000 years, because of one reason: because of those fanatic, extremist Jews who always preferred the law of God, this kind of nonsense, over reality and pragmatism on the ground. Always. And if they continue to do that, these are the biggest enemies of Israel.

One of the gatekeepers said to me: “How much time can you fight?” How many wars, with an island of 7 million people, surrounded by a billion or a billion and a half Muslims who hate us? How much time can we sustain that, and continue to be, in that bullshit phrase of Ehud Barak, “a villa in the jungle.” Not for long, this is what I feel. When you see what is happening in the Middle East now, there are tectonic changes all over. Egypt is on the move now. Syria, you don’t know what will happen there. Jordan is starting to move.

It’s in the best interests of Israel to try to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which is the wound that nourishes all the hatred towards the Israelis. Yuval Diskin told me: “Look, I don’t believe that there will be peace. But you have to move in small steps ahead, to build confidence, to build those methods that maybe will reach one day to a cessation of animosities.” I’m not saying to you that if we will start to speak, tomorrow a thousand white doves will spring out of the ground and everybody will live happily ever after. It’s a very, very tough task, but at least we should say that we strive for it.

“The Gatekeepers” opens this week in New York and Los Angeles, with wider national release to follow.

Shares