We are lousy with music memoirs that want to be literature. And as perfect as Patti Smith's "Just Kids" might be, there's something to be said for a book that takes delight in running into a former bandmate now working at a McDonald's in England.

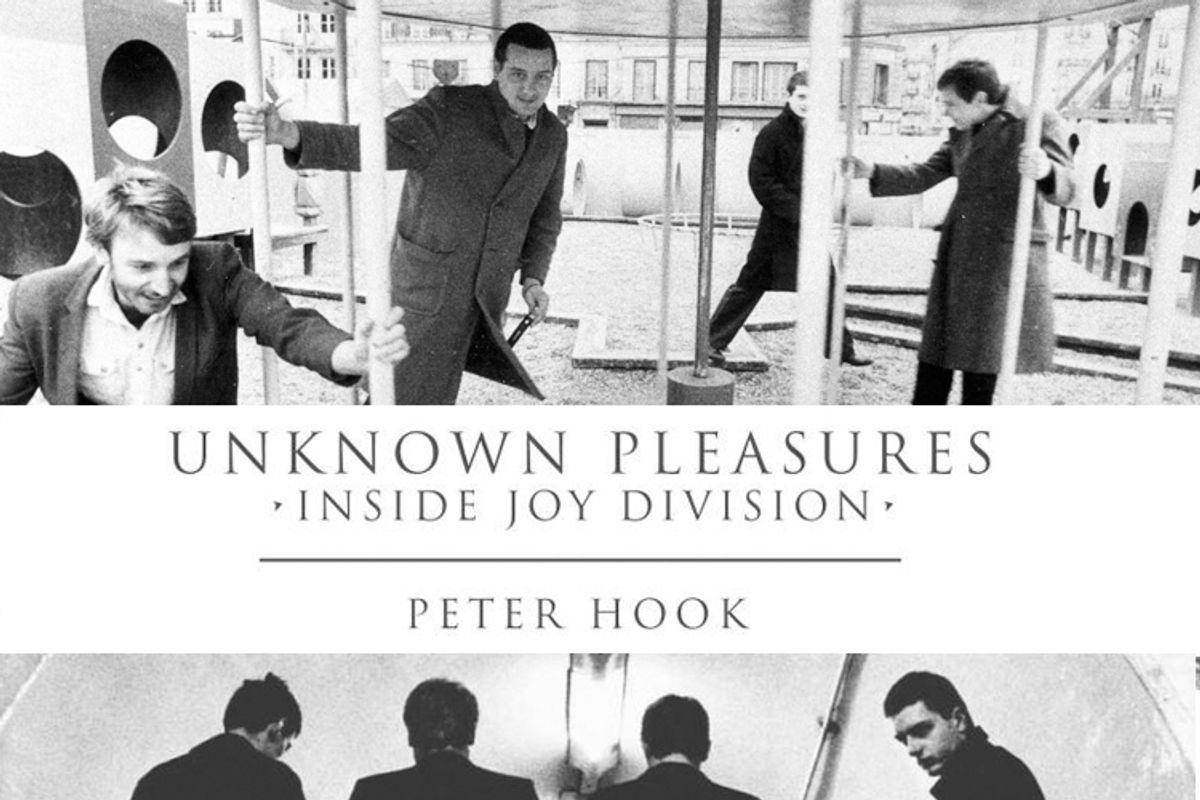

Peter Hook's "Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division," is a lot of things, all of them brutally honest and told in the straightforward voice of an English punk rocker who ended up playing bass in two of the most distinctive and influential bands of the post-punk era -- a band that's been enshrined in movies like "24-Hour Party People" and "Control," and whose influence can be heard in countless of the dark, arty, epic bands that followed, whether U2, R.E.M., Radiohead or Interpol.

Hook's path was set at a Sex Pistols show in Manchester in June 1976. Like the old cliché about the Velvet Underground, not many people were there, but all of them started a band -- the 50 people in the room included future Smiths singer Morrissey, Mark E. Smith of the Fall, Mick Hucknall of Simply Red, and Hook and soon-to-be bandmate Bernard Sumner.

Joy Division released two stone-cold classics, "Unknown Pleasures" and "Closer," icy, cerebral and brittle albums of spiky guitars and desperate, despondent lyrics by frontman Ian Curtis, delivered like epic pronouncements in songs like"Atmosphere," "She's Lost Control" and "Isolation." When Curtis hanged himself in May 1980 -- on the eve of the band's first American tour, and with the chilling single "Love Will Tear Us Apart" two weeks away from release -- he was elevated to the pantheon of tortured romantic rock icons. Hook, Sumner, drummer Stephen Morris and later Gillian Gilbert went on to provide the soundtrack for every college dance party between 1983 and, say, 1997, as New Order. (Hook relishes every sharp elbow thrown at his former bandmates, who have continued without him, while he has laid claim to the back catalog himself with Peter Hook and the Light.)

But the Curtis in this book is not the icon people might expect. Curtis might have loved experimental literature, and he might have fronted one of the best art-rock bands ever, but as Hook writes, he was also just another guy in the band -- a guy who loved carousing, dirty jokes and being one of the boys.

"A poetic, sensitive, tortured soul, the Ian Curtis of the myth -- he was definitely that," Hook writes. "But he could also be one of the lads -- he was one of the lads as far as we were concerned. ... He had three personas he was trying to juggle: he had his married-man persona, at home with the wife; the laddish side; and the cerebral, literary side. By the end he was juggling home life and band life, and had two women on the go. There were just too many Ians to cope with."

Over green tea in New York last week, Hook talked about the need to break past the Ian Curtis myth, why he and his bandmates had no idea the kind of pain their singer was in (even as fans most certainly did) as he pulled practical jokes and fought for the spotlight, despite epilepsy and growing depression.

Joy Division belongs to myth these days. There have been two movies and several books, designer sneakers, and even Mickey Mouse shirts designed in the band’s distinctive look. Interest grows with every new boxed set, or as every gloomy and atmospheric band from Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails to Interpol talks about their importance.

But the myth that has hardened is that Joy Division’s music is about death and isolation and despair – and, of course, that Ian Curtis hanged himself at 23 only adds to that brooding, romantic allure. But your book shows a very different side of Ian Curtis: He’s the guy who wrote “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” yes, but you show him pulling pranks and chasing women on tour – and with a distinct appreciation for toilet humor. Was humanizing the band, and pushing back against the myth, part of why you wanted to write this?

The humanization of it was always the part that I felt was lacking. I read one too many books about Joy Division by people who weren’t there, and they always seem to dwell on the dark, the intense, the miserable image of Joy Division. I’m happy to buy into it for the purposes of the myth, of course, but …

It sells a lot of T-shirts to a lot of teenage boys. Myself included!

(laughing) I was one of them, too. Because we didn’t do them ourselves, I had to buy the T-shirts as well.

I thought that I might get a bit of resistance by demystifying the group. But I wanted to do it just to show that we were human, and we made mistakes and learned on the way. It was a very difficult journey; it really was hard work. There was no respectability for it, something that surprised me actually, you know. Music was such an important part of everyone’s life in the '60s and '70s, but everywhere you played the music was dreadful.

So why was it so important to you to try and humanize the band after all this time?

I always felt that we went through some very, very funny happenings -- and Ian was always a part of it. He was never separate, he was never locked in his own dressing room with “I do not want to be disturbed.”

Right: I am reading William Burroughs and Kierkegaard now. Do not disturb me with your childish games!

There was that aspect to his character, but he was always part of the … jollity, I suppose you have to put it. He wasn’t separate. I think one side of him has been very characterized and the other side hasn’t -- and that’s the bit I lived.

If you read Keith Richards’ book, which I did enjoy, it felt to me like somebody had written the first 90 pages for him because he couldn’t remember it. But once you actually got into the bit of him talking, it’s amazing how many group members pretty much have the same experience.

You’re young, ambitious, on the road – and want to take advantage of everything that’s suddenly made available to you.

Yeah, and you get ripped off. But the interesting thing about the early days was that you were not doing it for money. You were investing in yourself -- and that made it so fine and noble, that blind devotion to what you were doing, against all odds, which is a crazy thing.

You were so convinced that you were the next best thing since sliced bread, and that’s what I love about people in groups. What I don’t recognize is the really weird thing you have now with “Pop Idol” and “X Factor,” where you are offering yourself and asking, “How am I? Can you tell me how I am?”

Yes, tell me how to change, you washed-up pop star of a decade or two ago, and that’s what I will do!

And that freaks me out. Because if you had Ian Curtis in front of Simon Cowell, I’ve got a pretty good idea of what Simon Cowell would have said.

And I think I know what Ian Curtis might have said. You write in the book that one of the things you value about Joy Division in those days is that you were all completely clueless.

(laughing) Still clueless! I love that young bands will do anything to succeed. We did that shit record (often bootlegged but never released) for RCA because the producer promised to take us to Paris. Paris, yeahhh! (laughing) Of course we’ll sign! As if it was the only way you are ever going to get to Paris. I wish I could start an advisory service to young bands, because you have to start off with the worst possible scenario. A friend of mine recently started managing a huge group, and he said to them: “If I’m going to be your manager, I want us all to sit down now and work out what’s going to happen when you all fall out.” And they were going, “We are never going to fall out; we love each other.” He sat there until they worked out what to do in the case of it all going wrong.

And with what has happened with me with New Order over the past year, I wish I had bloody done that, and really you have to write all of that down, (laughing) and give it to band members as they go in at 17, at 16, to start their first group -- because that way you can get some dignity at the end. The thing about New Order, their reformation, is that there is absolutely no dignity and that’s unsettling. We achieved so much and fought against all the odds and made it over and over again -- and now we are involved in this pathetic wrangle that shows no sign of being resolved and I can’t believe it. I mean, I am not going to give up because it’s not in my character, unfortunately.

Let me back up again to those early days. I think what would surprise most people is how funny and strange those stories are. At one point, the police track you down as a suspect in the Suffolk Strangler serial killer case, because the band’s van had been in the same sketchy neighborhoods as the murderer. There’s a brutal series of pranks on tour with the Buzzcocks, ending with Joy Division setting 10 pounds of maggots loose onstage during their set.

I don’t think we are alone in that. I think most groups have that. I just don’t think it gets reported (laughing).

It doesn’t exactly square with the serious image of a goth band on tour. You tell stories about Ian Curtis peeing in giant hotel ashtrays …

(laughing) It’s a lot like life, isn’t it? Really. The only complaints I’ve received about this book were from Bernard and Steve (laughing) and Gillian, too. Yeah, she accused me of writing ill of the dead, and I was thinking, “What fucking book is she reading?” I mean, I knew she was a bit of a dick. I don’t think I speak ill of the dead. But you know, you can’t change an opinion.

They have always been anti-everything that I’ve done outside of New Order. Which I suppose in a funny way, you could put down to protection. Before the group split in 2006, it felt OK for us to ignore everything to do with Joy Division, because we decided to do that in 1980 when Ian died. We stuck with that, and it worked for New Order. But Joy Division had achieved so much for their very brief career -- and yet we never celebrated anything, nothing, not one single thing. It just seemed wrong, you know, especially when you watch other people celebrating far less important happenings. And that was the reason why I decided to celebrate 30 years of Ian’s life, was … because it seemed ridiculous not to. It seemed a bit disrespectful to me because it’s like you were feeling guilty about celebrating things that he’d -- we’d -- achieved as Joy Division. The others have done nothing but rail against it.

While still playing the songs in their sets in America last year.

Yes. Before me. [laughs] That is the weird thing that I haven’t quite gotten my head around yet. But, I mean, in New Order it was always not “do as I do.” It was always a little bit too much “do as I say.”

We keep sliding into New Order, but I’d like to know more about Ian. You write that you never really paid attention to his lyrics – that they were too hard to hear over the music. You just thought that they sounded cool.

Yeah, well, I mean, it was the passion with which he delivered them. Really, in a funny way, I suppose it’s like in war, isn’t it? If you’re all going over the top, and the officer is there at the front going, “C’mon lads! We’re going to go!” and you’re like, “Yahhhh!” You’re all ready for it. If the guy’s hidden in the corner, going, “Off you go,” it’s not right, this. But Ian did deliver, and that was what I loved about Bernard as well, honestly. When we played, Joy Division, everybody felt they were giving it their all. It’s the only time I’ve had in my career that’s actually felt absolutely right. That’s Joy Division. Which is actually quite strange. I suppose you’re always trying to live up to the first ideal. It’s quite an odd situation to be in. But, I mean, the one thing about Ian was that he didn’t disappoint. When you did start to look at the lyrics, and read them, when you got the opportunity when we’re doing “Unknown Pleasures,” they were fucking great. Fantastic. And the same way that I’d never really heard Bernard’s guitar lines for most of the songs. So I sat down with “Unknown Pleasures” and I was like, “Wow. Fuck, this is great.” I mean it was really a strange thing to go through, and it all comes down to the fact that the equipment was shit. Ian particularly suffered badly at the hands of the equipment. You just couldn’t hear it. Yeah.

You didn’t read reviews, or listen to the albums at the time? And since you couldn’t make out the words, you had no idea that this person you were spending so much time with was also a tortured soul and in considerable emotional pain?

You didn’t know. No, no, no. I mean, I must admit, that if you look back on the lyrics of “Closer,” you could derive that. You could come to that conclusion, right? But the thing is, that was in complete contrast to him, how he was acting as a person. He wasn’t there on the floor, curled up in a ball, with his head in his hands. He was actually, most of the time, acting quite normal. Quite nice.

Pete Saville [the Factory Records graphic designer who created the band’s striking visual imagery] did say that if we’d have all looked at the lyrics of “Closer,” we would’ve stopped him. But I don’t think we would’ve.

In the liner notes to the “Heart and Soul” boxed set, you said: “It was like a snowball going down hill. It’s a great shame because you should’ve been able to just hear it and say, ‘Ian, can we have a chat with you? What’s the matter?’ But when you’re young, you don’t notice things.”

No, you don’t. And I think it’s also, “I do not care.” That’s a cheat that you’re allowed to get away with because you’re young, especially when you’re in a group. I really regret not going to see him, when he was dead, to say goodbye. And I was young. And so I said I’m not going. Someone should have said, “Fucking go, because you’re going to regret it for the rest of your life.” I do wish somebody would have said that to me. Because I have regretted it.

But no other regrets? You dropped him off at home on Friday evening, and just days later you’re supposed to be heading to America for your first shows here. You were both excited. And then Sunday he’s found dead. Were there clues you missed?

No, no … it’s mainly to do with Ian. The frustration. I’ve lost a few other people to suicide. And it’s the same feeling with all of them. The helplessness and the helplessness -- and the guilt that you feel stays with you and always will. You know, they’re free; they’re off with the fairies hopefully. But it’s you who has to shoulder the burden of guilt, which is the unfortunate thing. But that’s the name of the game. Suicide does that.

You suggest in the book that there were so many different Ians, and he showed a different face to different people in his life. One of the regrets you mention is teasing him over an affair he was having with a journalist who seemed a little arty and pretentious. “I feel terrible about it now,” you write. “Now I’m older and wiser and now I’ve looked at his lyrics and worked out what a tortured soul he was. We should have left him alone to have his love affair but we didn’t because he wasn’t tragic Ian Curtis the genius then. He was just our mate and that’s what you did with your mates up North: you ripped the piss out of them.”

Yes, in a normal way. You know, I think that we all do that. We show a different face to your boss, a different face to the dog, a different face to the missus. I don’t think it was primarily Ian’s, you know, domain. But the thing was, is that it made it very confusing for you.

The problem that everyone was aware of was Ian’s epilepsy – in nearly every show you played near the end, Ian had seizures onstage, and they sound truly terrifying. But he never wanted to stop.

On the one side, you wanted the group to succeed, but on the other side you felt the group was killing him. And that was hard to reconcile -- yet the person who most wanted to succeed was Ian. He wouldn’t stop fighting. And I think really, the thing about illness, any degenerative illness like that, is that when you do start fighting, you tend to succumb. And I think that maybe in his mind that’s what he was thinking: “I’m not giving up because I won’t acknowledge it.” And that fight really was just as important to him as it was to us.

You call it “the selfishness, stupidity and willful ignorance. But this is what we had all worked for.” And it was right there in front of you at that moment -- and all of you wanted it.

Yeah. And he didn’t want to let us down. He did not want to let us down, he didn’t.

He fought it tooth and nail, God bless him. Right to the end, yeah. You know, I wouldn’t do it now -- if it was me, I’d just go, “Piss off! I’m off, no way.” You just wouldn’t do that. It’s amazing to think that we began to think that that was OK, to take that chance. Because it was a bit like Russian roulette.

In the book, you say that “I look back and keep seeing where we should have stopped.”

Yeah. But you didn’t know. Because he didn’t want to. If he had wanted to, I think we would have done it. Because you weren’t forcing him. There might have been a bit of coercion, maybe, because none of us wanted to admit that it was, you know, a path to destruction. And also, as you said before, you didn’t want to lose the opportunity. But there’s a lot of other people in between, who were a lot more worldly and a lot more experienced than all of us, who should have been able to say, “Hang on. Pack it in.”

What was it like to record “Love Will Tear Us Apart”?

The recording for “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was stuck on the end of the sessions for “Closer.” So, we recorded it probably about four or five times because (producer) Martin Hannett in particular had trouble with that song. That one out of all the tracks that we did gave him the most … what can we say … he found it enormously difficult to do it justice. He couldn’t decide whether it should be fast, slow, loads of overdubs, stripped down. He just couldn’t get it. And he worked for it for so long, I mean it was annoying the shit out of him. Everybody knew that it was a belter. So everybody was always dying to chip in -- do this, do that, try this, try that. And he hated it. That’s why he ended up locking himself away and trying to finish it in the middle of the night, so nobody would get there. Yeah, I mean, it was bizarre. But Martin was such a bizarre character. Very nice, but obtuse beyond belief. I mean, you know, just like Phil Spector. Very, very weird character in the way that he had total belief in himself and thought that your opinion meant nothing at all.

So that horrible Sunday when you got that phone call that Ian has killed himself, and the single “Love Will Tear Us Apart” with the cemetery photo on the cover is scheduled to come out two weeks later, what is going through the minds of everybody during those weeks? I mean, listening to that song must have been chilling. It’s still chilling to hear now.

I think we were definitely in shock, without a shadow of a doubt. And we didn’t know what to do. And the scary thing was the helplessness. You know, you were really relying on [Factory Records head] Tony Wilson and [band manager] Rob Gretton to get us through it, we really were. And I don’t think we gave a thought to anything after that. Once Ian had gone, nothing was important. I remember very well sitting in my car and listening to it, when it came in the charts, and feeling absolutely nothing. Nothing. Came straight in at No. 13 or something, or 11 or something like that, and it just absolutely meant nothing. You know, I was actually happy in the cocoon of New Order, to be honest, just able to ignore it.

That Sunday, you very quickly made the decision to move on without him, and Joy Division became New Order.

Yeah, I mean we didn’t want to go back to work, you see. You’d had the carrot dangled, you’d enjoyed it, you’d enjoyed being artistically and creatively satisfied -- and none of us wanted to go back to work. And I can safely say that that first Monday when we came back in to work together, there was no plan. It was literally about hanging on by your fingernails, and we did it very well, you know, we got through it. New Order was more successful, many times more successful, than Joy Division.

But was it fun for you at any moment, ever again? Because you suggest that after “Movement,” things were never the same between you and the rest of the band.

It was like a table with a wonky leg. Like, every so often it would come out and annoy you. And then it’d go back. And then it’d annoy you again.

You said in the book that you liked them as bandmates -- but “as people, as friends, not really.” Everybody kind of imagines these groups being sort of bands of brothers, but it’s so rarely the case.

No, no. I think there was a subtle shift in New Order when Bernard started to get a lot of power after Rob’s nervous breakdown, and Bernard ended up in charge. And I think the problem was, was that I didn’t actually agree with a lot of his policies, shall we say. And I kept quiet. While I was drinking, it was easy to keep quiet. Just go off and get drunk. Once I stopped drinking, I realized that I had to do something about it. And my mates did say to me that, you know, the clarity you get when you sober up is startling. He said, beware. And that was the reason, you know, the old policies were so entrenched that there was no compromise. I think Bernard definitely thinks that compromise is something that other people do. Without a shadow of a doubt. And he’d always give you a thousand reasons why you shouldn’t do what you wanted to do. It just got to the point where it crossed the line.

Is there any going back over that line? Could you ever see playing with them again?

Not at the moment. It’s like a divorce where you’re at your worst, worst point. And my lawyer keeps saying to me, “Well, once you sort this out, and everyone’s happy, then it will heal.” At the moment, they’re happy, I’m not. So, ain’t gonna heal. And really, they seem to be as happy to carry the war on, especially verbally, as I am. So, yeah. You’ve got the worst thing in the world, haven’t you? Bunch of bloody school kids.

But, I mean, it comes to a point in your life when you do have to stand up and be counted. And in 2006, I felt that. I had to stand up and be counted. And there was a lot of carrots dangled in front of me, to keep my peace. But, you know, ultimately, being able to get up in the morning and smile and be happy, to do what you’re doing, is more important than looking at your bank balance. And it does amuse me that Bernard keeps accusing me of doing it for the money. Because being a musician is one of the only jobs in the world where being accused of doing it for the money somehow becomes an insult. “You’re only doing it for the money.” And you won’t say it to a taxi driver, would you? You won’t say it to a waiter. Because you’d go, “You’re fucking doing it for the money, you dickhead.” “What do you think I’m doing it for, yeah?”

What are the main issues?

In the New Order battle? The main issue is that they set up my alimony. And that’s it. And I don’t agree. And I also don’t agree with the fact that they used the name without consulting me or asking me, because I think there’s a big difference between doing Bad Lieutenant [Sumner’s band after the 2006 New Order breakup] to masquerading as New Order. It’s like Peter Hook & the Light, saying, “Fuck it, let’s call ourselves Joy Division.” That to me is the difference, and I wouldn’t have the gall to do it. But I do understand that Bad Lieutenant weren’t a success, and we are in a very bad economic time.

It’s easier to charge $100 a head if you’re New Order …

If you’re called New Order, yeah. I mean it’s all about use of the trademark. Because the thing is, I think that those gigs that New Order are playing, so-called New Order, a lot of the people don’t even know I’m not there. Because a lot of the people come to me and go, “Great gig! Saw you in August.” And I’m thinking, “Fuckin’ hell.” [laughs] But I always go, “Yeah. It was great, actually.” You know, because it’s not really worth arguing, but what Bernard, Stephen and Gillian have decided to do is say that I am not important in New Order. And that’s the fact.

What happens to Peter Hook if you’re not at that Sex Pistols show?

That’s a very good point, and I did think about that. At many occasions through the course of that book, I kept thinking, “What if I hadn’t gone to that gig?” Fuck it, you know, that is one thing we will never know. Thank God.

Will there be another book about the New Order years?

Yeah, yeah. The wonderful thing about this book is that it’s unusual, in that it’s not sullied by money, it’s not sullied by any kind of normal sex and drugs and rock n’ roll. But New Order -- I went for it lock, stock and barrel in New Order, so really, it’s the only thing.

Shares