We’ve seen senators like Ted Cruz before. The historical comparison most commonly invoked involves Joe McCarthy, whose scurrilous red-baiting crusade in the early 1950s shattered the careers of innocent public servants and alienated McCarthy from his fellow senators, but also made him a folk hero on the right. Jesse Helms comes to mind too. The far-right North Carolinian was generally seen as more trouble than he was worth by his party’s establishment (there were those in the Reagan White House who not-so-secretly rooted for his defeat in a close 1984 campaign against Democrat Jim Hunt), but the intense animosity Helms stirred among liberals only enhanced his status among the conservative masses.

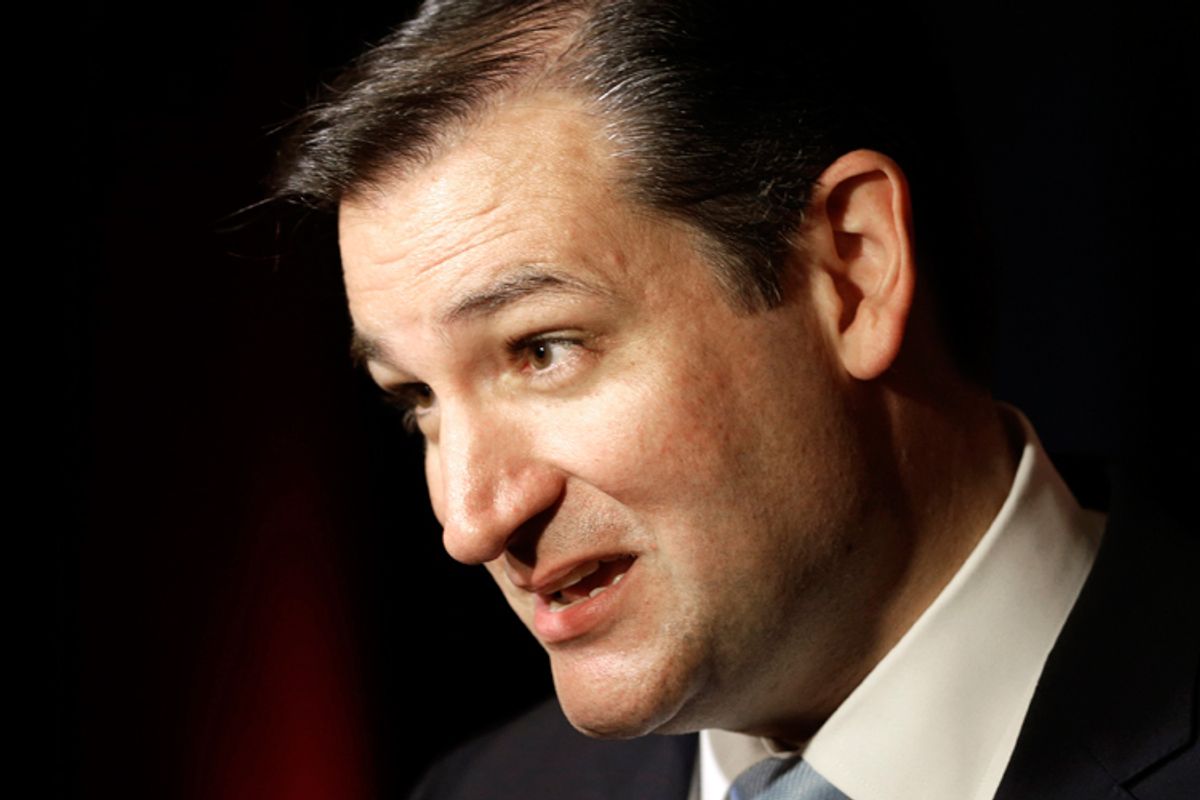

So it goes for Cruz, the freshman Texas senator who in his first two months on the job has baselessly asserted that Chuck Hagel might have received money from the North Korean government, reiterated his belief that there were 12 Communists on Harvard Law School’s faculty when he was a student there, and delighted in playing the role of ideological purist, even – or especially – if it puts him at odds with fellow Republicans.

The Hagel attacks have drawn cries of McCarthyism from the left, a torrent of negative media coverage, and earned Cruz a public rebuke from John McCain. But none of this has bothered Cruz, and for good reason: His standing within the conservative movement is only growing. Cruz has treated all of the negative attention as noise generated by Democrats, the liberal media and impure Republicans who are uncomfortable with a conservative true-believer rocking the boat in Washington. Conservative activists and media personalities have run with this narrative. As the Austin Statesman put it over the weekend,

Six weeks after being sworn in, Ted Cruz returned to Texas a commanding figure, the center of attention in the Senate and the national media, loathed by the Washington establishment and, for that, all the more celebrated by conservatives nationally who found in him a champion both very smart and, it seemed, utterly fearless. He had emerged from his baptism by fire more powerful for it, not only in national conservative circles but, by leveraging his new-found status, perhaps also in the Capitol he had so unsettled.

For Republicans who believe their party’s post-2008 direction has been self-destructive, Cruz’s rapid rise is a troubling development, because it really has nothing to do with policy and everything to do with the outrage he provokes from Democrats and the media. The thorough beating they took at the polls last fall perhaps should have prompted rethinking on the right. But conservatives’ appetite for Cruz shows that the GOP base’s animating spirit still hasn’t changed: Loud, aggressive and reflexive hostility to President Obama, the Democratic Party and any Republican who would dare contemplate compromise is still how “conservatism” is defined.

What makes Cruz and Cruz-ism a particular problem for his party is the demographic conundrum Republicans now face. Obama’s reelection (and Democrats’ unexpected gains in the Senate) was testament to the rising clout of the “coalition of the ascendant” – African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, women (particularly single women), Millennials. As Joan Walsh pointed out last week, Cruz’s Cuban-American background by itself won’t improve his or his party’s standing with Hispanics or other minorities. Instead, he’s appealing to the aging, overwhelmingly white core of the Republican base – voters whose grievances against the government in the 1970s and 1980s turned them against the Democratic Party and attracted them to Ronald Reagan and his ideological descendants.

So Cruz is now positioned as a major obstacle to the ideological modernization that the Republican Party is desperately in need of. If his brand of conservatism is treated as the gold standard of purity by the conservative media and conservative activists, Republican leaders will have a hard time moving the party away from its Obama-era orthodoxy. This could affect the calculations of Republican office-holders in the coming months, as Congress tackles immigration, guns and other issues on which the GOP is out of step with mainstream opinion. It could also lead to more trouble for the party in Senate races next year. In some states, like Cruz’s Texas, it really doesn’t matter whom the GOP nominates; the party will win anyway. But in other states, the nomination of a Cruz-like candidate can be an act of electoral suicide.

When firebrands like McCarthy and Helms were on the scene, the Republican Party was more geographically and ideologically diverse. In McCarthy’s time, for instance, liberal Republicans from the Northeast loomed large in the party – a key reason why Dwight Eisenhower, who governed as a moderate, managed to beat back the ultra-conservative Robert Taft in 1952. And through the 1980s, Republican presidential candidates regularly contested and won large industrial states. The political damage that McCarthy and Helms did to their party was limited.

But the GOP’s appeal has narrowed in the last decade or two. That doesn’t mean the party is doomed, but it does need a reboot – a reboot that’s difficult to envision as long as the party’s base continues to celebrate behavior like Cruz’s.

Shares