Why would anyone want to buy a newspaper these days? This is the question originally raised by my recent Harper's magazine investigation into the state of the newspaper industry and now resurrected by this weekend's New York Times report on the possibility of Koch Industries buying the Tribune Co.'s eight newspaper properties. The answer is that for all the problems they face, newspapers still offer something extremely valuable to a particular kind of investor -- just not what they might publicly admit to because it is more than a bit unseemly.

In public, of course, prospective newspaper buyers continue to pretend that they are primarily interested in purchasing newspapers either to 1) preserve a venerated civic institution and objective journalism or 2) to seize an honest, straightforward business opportunity.

The former was the official rationale from a consortium of investors when they organized to purchase the Inquirer. Somehow, everyone was supposed to forget the fact that the consortium was not composed of those with a history of protecting the objectivity of journalism. Instead, it was made up of political and corporate power brokers with vested interests in skewing the state's news.

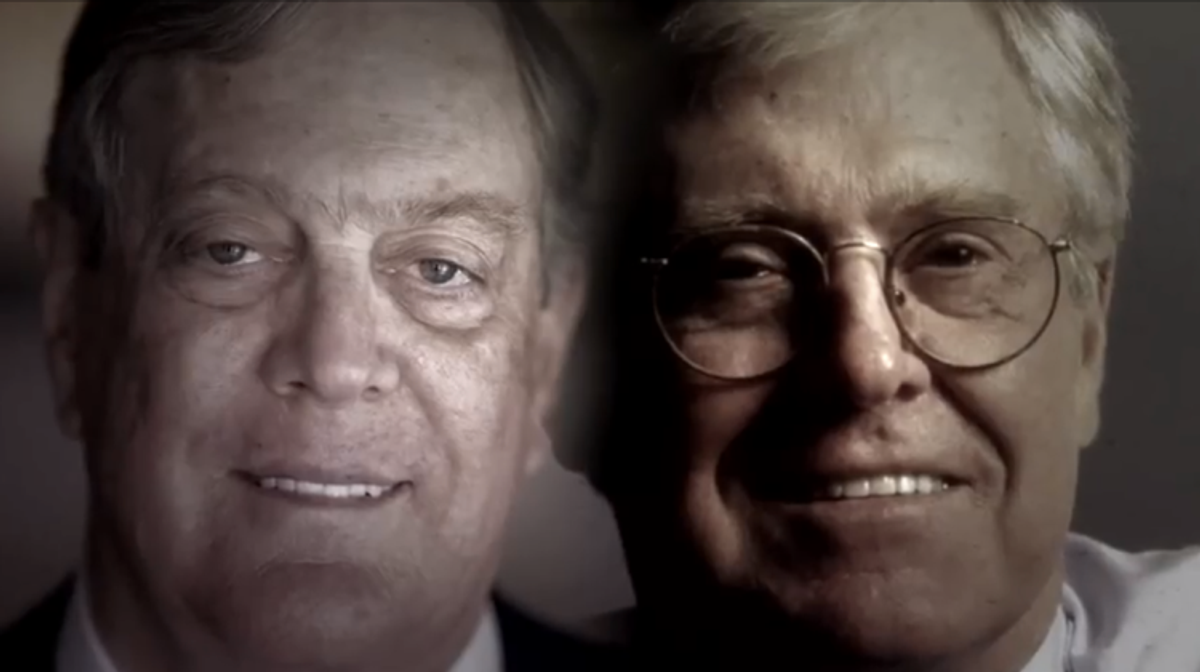

In the Koch situation, we are being treated to the second rationale, the one about business. In the Times report, an adviser to the company "said the Tribune Company papers were considered an investment opportunity, and were viewed as entirely separate from Charles and David Kochs’ lifelong mission to shrink the size of government." And a spokeswoman for the company insisted that politics has nothing to do with the potential acquisition.

"As an entrepreneurial company with 60,000 employees around the world, we are constantly exploring profitable opportunities in many industries and sectors," she said. "So, it is natural that our name would come up in connection with this rumor."

Like the "civic duty" justification, this carefully sculpted line is a devious misdirect, at once a blatant lie but also specked with a kernel of truth.

First the lie: As a business venture, newspapers do not look like a particularly promising venture unto themselves, to say the least. As Pew's Project for Excellence in Journalism shows, the newspaper industry is hemorrhaging money in the Internet era. The Tribune Co. isn't immune to the losses; on the contrary, it has lost so much cash that it has been driven into full-on bankruptcy. So the idea that the Kochs might buy the papers because the papers themselves are just any old companies that look like good bets to make money is hard to take seriously, especially coming from shrewd businesspeople like the Kochs.

However, that's where the kernel of truth comes in. Koch Industries is a conglomerate that does business in a number of sectors and that relies on particular public policies for its profits. For such a sprawling corporate behemoth, newspapers are a decent investment, just not in the way corporate leaders may want to admit in polite company. They don't necessarily want to admit that while the papers themselves may lose money, they can be incredibly valuable to the corporate parent because they can deviously skew the news in a way that serves the larger company. In other words, newspapers can become a crucial part of a corporation's larger profit-generating political machinery by specifically manufacturing the Overton windows that determine the public policies on which the corporate parent relies.

This is the truth I uncovered in my Harper's magazine investigation into what I call the New Citizen Kane Era. Simply put, even as newspapers are losing money and firing staff, they are in many ways more influential than ever before in determining the scope of what's considered "news" -- and what is not. That's because compared to radio, television and Internet outlets, they still employ, by far, the most journalists. Consequently, while radio, television and Internet outlets may be proliferating, the Congressional Research Service notes that those outlets often simply “piggyback on reporting done by much larger newspaper staffs." Put another way, most radio, TV and Internet outlets simply serve as an amplifier of both what newspapers report and how those newspapers report it, meaning that, as Pew puts it, “most of what the public learns is still overwhelmingly driven by traditional media — particularly newspapers.”

As I summed it up in Harper's:

For you, the news consumer, this means that the Ron Burgundy on your local evening news program, or the radio announcer you listen to each morning during your com- mute, is relying more than ever on the old “rip and read” trick—tearing out stories from the monopoly newspaper and reading them as original news. As an investment, then, monopoly broadsheets and tabloids remain a jackpot for a particular kind of buyer: the industrialist or politico who wants to control the core commodity on which most other news products rely.

This is how we know the Koch brothers' interest in the Tribune Co. is the opposite of what they claim. It is not about them simply looking for any old set of companies to turn around, as their innocence-feigning spokespeople insist. It is all about a set of new-era Citizen Kanes buying the kind of properties that can powerfully suffuse the entire news ecosystem with a hard-edged ideology -- the kind that serves those Citizen Kanes' political interests.

No doubt, this is why, according to the Times, the original idea for the Kochs to buy Tribune originated not at a business conference filled with MBAs and corporate turnaround specialists, but at a meeting about politics dominated by conservative activists and operatives. It is the same reason why political activist Douglas Manchester openly admits his recent purchase of San Diego's largest paper is less about making money off the paper itself than using the paper to push what it calls a "pro-conservative, pro-business, pro-military" political agenda. It is the same reason why Denver Post publisher Dean Singleton is accurately described by Campaigns and Elections magazine as a Republican political activist and why 5280 magazine notes that politicians now must "regularly run their ideas by him and try to avoid unflattering Denver Post coverage."

In all of these examples, as in so many others, we see that as newspapers are put on the auction block by profit-focused public companies, Citizen Kanes (whose status as private owners gives them more freedom to lose money on the ventures) are buying them up because they see those papers as a way to increase their political power by stealthily embedding their ideology and political interests into the very foundation of news.

How does this work in practice? My Harper's report is filled with myriad examples, from Manchester using his paper to promote a real estate venture he could be in a position to make big money from to allegations that the former Tribune owner Sam Zell used the Chicago Tribune to try to score himself a state-funded Wrigley Field deal. In the Koch brothers case, you could likewise imagine a Koch-owned Los Angeles Times making sure its coverage of energy is entirely pro-petroleum and supportive of oil industry tax breaks, thus creating a ripple effect of derivative media (TV, radio, Internet) amplifying the same skewed viewpoint. And while in that situation the Times may still lose money on its print sales, it would still be incredibly valuable to Koch Industries as a whole.

Many conservatives, of course, will cheer the Koch purchase of the Tribune, if it happens. But what's happening in the newspaper industry -- and, by ripple-effect extension, the entire news industry -- isn't really a left-versus-right, Republican-versus-Democrat issue. It is more an issue of objectivity and propaganda.

On one side are those who believe news that bills itself as objective should strive for objectivity and that when bias and ideology come into play, it should be openly acknowledged as it is in explicitly opinion-journalism publications on both the right and left. On the other side are Citizen Kanes who believe that news should be a delivery system for their propaganda. Wise in the ways of influence, these moguls know full well that the most effective form of propaganda is that which is baked into seemingly objective news and therefore doesn't look like propaganda at all. They also know there is no better way to do that today than to buy a newspaper.

Shares