"A mind always employed is always happy. This is the true secret, the grand recipe for felicity."

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to his daughter Martha, May 21, 1787

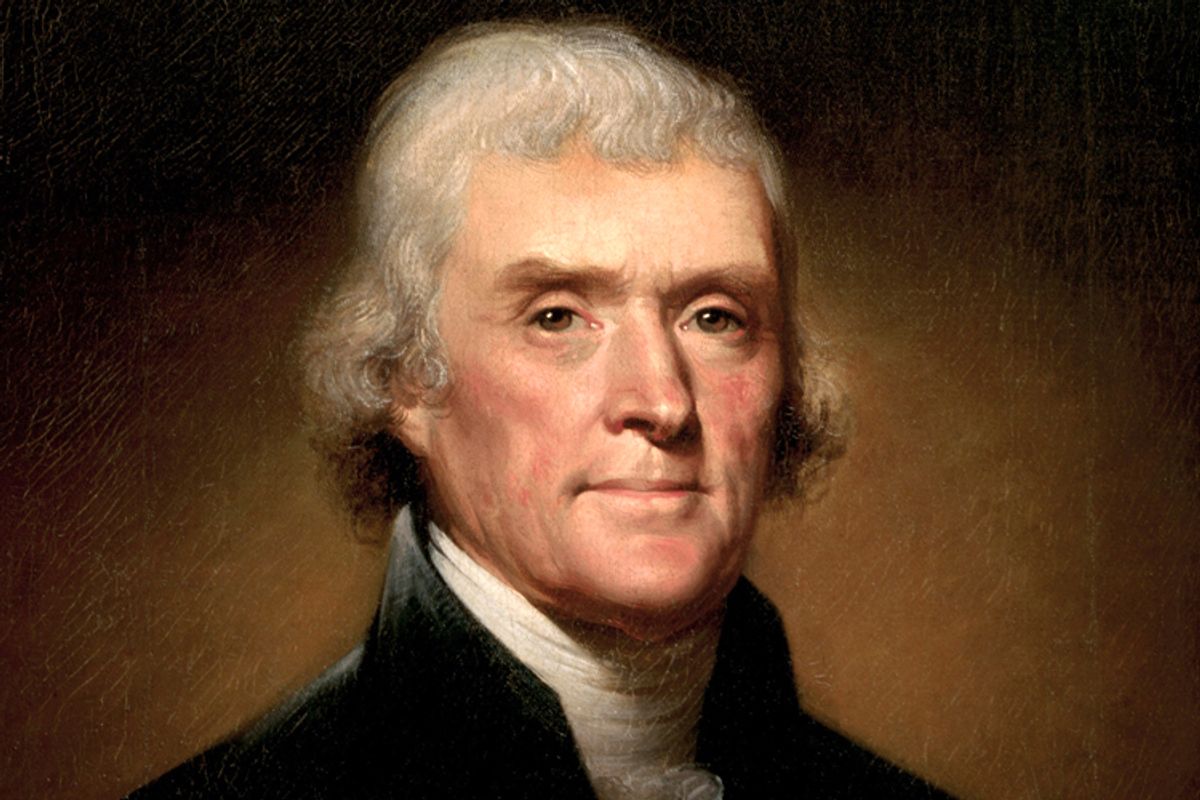

On the morning of Monday, July 1, 1776, Thomas Jefferson had, it can safely be said, a lot on his mind.

On that fateful day, the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia was to consider the resolution, first introduced on June 7 by his fellow Virginian Richard H. Lee, to dissolve “all political connection between [the Colonies] and the state of Great Britain.” And as soon as that resolution passed, as Jefferson expected it would, his draft of the Declaration of Independence, which he had completed the previous Friday, was due to come to the floor for a vote. Hyper-sensitive to criticism, the assiduous thirty-three-year-old wordsmith dreaded the thought of any tinkering with his text. (In fact, for the rest of his life, Jefferson would be bitter about the “mutilations” that his congressional colleagues were about to make, which reduced its length by about 25 percent.) He was also unnerved because the war effort of the new nation-to-be was not going well; the American troops in Canada, who lacked essential provisions due to a shortage of money, had just been hit by a smallpox epidemic. “Our affairs in Canada,” Jefferson wrote later that day to William Fleming, a delegate to Virginia’s new independent state legislature, “go still retrograde.”

The six-foot-two-and-a-half-inch delegate with the angular face, sandy complexion, and reddish hair was also dogged by a host of domestic concerns. He was still recovering from the sudden death—her illness lasted less than an hour—of his fifty-six-year-old mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, three months earlier. For most of April and the first part of May, Jefferson was detained by incapacitating migraines at Monticello, his five-thousand-acre estate, then a two-week journey by horseback from Philadelphia. And with his frail wife, Martha, pregnant for the third time in six years, he felt, as he informed Virginia’s de facto governor, Edmund Pendleton, on June 30, that it was “indispensably necessary ...[to] solicit the substitution of some other person” to take his seat in the Continental Congress by the end of the year. As it turned out, an anxious Jefferson couldn’t even wait that long; on September 2, he would submit his resignation and return to his “country,” as he still called his native Virginia.

Amid all the uncertainty and anxiety that he faced early on that sweltering July morning, Jefferson did a surprising thing. He started what turned out to be a massive list. For Jefferson, as for other obsessives, list making was a passionate pursuit that could help him get his bearings. Flipping his copy of The Philadelphia Newest Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord 1776 upside down, he wrote on the first interleaved blank page at the back, “Observations on the weather.” Below this heading, he set up three columns, “July, hour, thermom.” At 9 a.m., he recorded 81 1⁄2. With the debate on Lee’s resolution taking up most of the day, Jefferson did not do another temperature reading until 7 p.m., when he recorded 82. But for the rest of that momentous week and for years on end, he would record the temperature at least three times a day. On the fourth, when the mercury hit 68 at 6 a.m. before reaching a fitting high of 76 at 1 p.m., he even managed to squeeze in a total of four readings. On the day that the Declaration was signed, Jefferson also made the fifteen-minute trek from his room at Seventh and Market to John Sparhawk’s book and gadget store on Second Street, where he shelled out 3 pounds, 15 shillings (the equivalent of several hundred dollars today) for a new thermometer. On Monday the eighth, as he recorded in the account book, which he kept on the interleaved pages in the front half of his almanac, he returned to Sparhawk’s to purchase a barometer for 4 pounds, 10 shillings.

Jefferson had been fascinated by meteorology ever since his undergraduate days at William and Mary. In Williamsburg, he had befriended Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier, a London-born Fellow of the Royal Society, who was well connected in scientific circles. In 1760, Fauquier, who possessed the latest versions of the major scientific inventions of the day— the thermometer, telescope, and microscope—had begun a weather diary (which was limited to just one reading a day). Inspired by this adolescent hero, Jefferson would establish himself as an international authority in the field. In a chapter in his scientific treatise, Notes on the State of Virginia, first published in 1785, Jefferson summarized some preliminary findings. In the age-old debate about climate change that dated back to the ancients, Jefferson (like another prominent Southern politico who served as vice president exactly two centuries after he did) came down squarely on the side of “global warming.” (But in contrast to Al Gore, who has warned of the dangers associated with greenhouse gases, Jefferson was hypothesizing about how events such as deforestation could be “very fatal to fruits.”)

“A change in our climate...is taking place very sensibly,” he concluded, based on his assessment of decades of data collected by himself and others. “Both heats and colds are become much more moderate....Snows are less frequent and less deep.” Jefferson, who bought about twenty thermometers during the course of his life, would continue to gather a wealth of weather data, which he crunched every which way, until 1816. Even during his presidency, he took the temperature at both dawn and 4 p.m. The National Weather Service, established in 1870 as the Weather Bureau, has hailed Jefferson as “the father of weather observers.”

But a thirst for knowledge wasn’t the only reason why Jefferson began this ambitious new scholarly undertaking at what turned out to be a pivotal moment in world history. Compiling and organizing information, as he well knew, could also help calm him down. “Nature intended me,” he later wrote, “for the tranquil pursuits of science by rendering them my supreme delight.” Distracting himself from his innermost thoughts was his way of warding off feelings of despair. While Jefferson was a gifted singer, he often used his musical talent, like his ingenuity, to hide from himself. One could “hardly see him anywhar outdoors,” his slave Isaac once noted, “but that he was a-singin’.” He would even sing while reading. His habitual manner of coping with stress was to do not less, but more. In contrast to most people, who become undone when they take on too much, Jefferson became energized. His constant fear was not having enough to occupy his mind. For Jefferson, whose personal credo was a mishmash of Epicureanism and Stoicism, happiness was synonymous with virtuous work. “Nothing can contribute more to it [happiness],” he later mused, “than contracting a habit of industry and activity.” In contrast, he considered idleness “the most dangerous poison of life.” To be fair, his was not an introspective culture; as one historian has put it, eighteenth-century Virginians had “neither the taste nor the skill for self-examination.” Even so, the vehemence with which Jefferson avoided experiencing internal distress qualifies him as an outlier.

The pedantic side of this patron saint of polymaths has often been overlooked. Most Americans associate Jefferson only with his staggering intellect. As President John F. Kennedy put it at a White House dinner honoring fifty Nobel laureates a half century ago, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” Few are aware that America’s “Apostle of Freedom,” as President Franklin Roosevelt called the most erudite Founding Father, was as consumed by the petty as he was by the lofty. The nonstop doer was not always discriminating in what he did. Jefferson delighted in gathering factoids, regardless of how meaningful they might turn out to be. He was also eager to communicate what he reaped. “[Jefferson] scattered information,” Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania observed in 1790, “wherever he went.” During his presidency, he kept a long list with the equally long-winded title, “A statement of the vegetable market in Washington, during a period of 8 years, wherein the earliest and last appearance of each article is noted.” As this document reveals, while entrusted with running the country, Jefferson felt compelled to keep constant tabs on the availability of twenty-nine vegetables (and seven fruits) in our nation’s capital. The earliest date on which he could enjoy a watermelon at the White House was July 7; the latest was September 4. And when his eldest grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, who was about to spend a year studying science in Philadelphia, visited him in Washington in 1807, the president immediately asked the fifteen-year-old to empty out his trunk so that he could personally examine every article. Having completed this inventory, Jefferson took out a pencil and paper in order to make a list of other items that he was convinced the adolescent would need.

Keeping track of minutiae was a lifelong preoccupation. Jefferson kept in his pocket an ivory notebook—a kind of proto-iPad on which he could write in pencil; and when he returned to his study, he would then transfer his data to one of his seven permanent ledger books. In his Garden and Farm books, which he kept for more than fifty years, he recorded all the goings-on at Monticello. “[H]ad the last dish of our spring peas,” he wrote on July 22, 1772, in a typical entry in the Garden Book. And in his account books, which he maintained for nearly sixty years, he kept track of every cent he ever spent. “Mr. Jefferson,” the overseer at Monticello once observed, “was very particular in the transaction of all his business. He kept an account of everything. Nothing was too small for him to keep an account of it.”

All this financial calculating did not do much for Jefferson himself. One reason why obsessives love control—or, to be accurate, the illusion of having everything under control—is that they can easily be overwhelmed by their own impulses. A man with sumptuous tastes, Jefferson never could get a handle on his own penchant for runaway spending; during his eight years in the White House, he would shell out $10,000 ($200,000 today) on fine wines. But while he would always be in debt and would saddle Thomas Jefferson Randolph, the executor of his estate, with a $100,000 ($2 million) tab, time and time again, America benefited from his interest in systematically tracking the smallest of expenditures. After all, Jefferson created the penny as we know it—an innovation that would help put the whole country’s finances in order. On account of this little-known legacy, to this day, Americans have Jefferson to thank every time they open their wallet or balance their checking account.

*

Jefferson would never get over the death of his wife. In November 1782, he wrote a friend that he was “a little emerging from the stupor of mind which has rendered me as dead to the world as she whose loss occasioned it.” In an attempt to short-circuit his mourning, he jumped back into politics. In June 1783, Jefferson was one of five delegates selected by the Virginia General Assembly to serve in the new Continental Congress. On May 7, 1784, Congress appointed him a minister plenipotentiary; his assignment was to travel to Paris to assist Benjamin Franklin and John Adams in negotiating commercial treaties with European nations. To prepare himself for his new job, the data collector went into overdrive. Over the next two months, as he made the trek from Annapolis, where Congress was meeting, to Boston, from where his ship was to leave, he gathered massive amounts of economic information on each state that he passed through. His twelve-part questionnaire, which he filled out by meeting with leading merchants and public figures, covered everything from the wages of carpenters to the size of fishing vessels.

On July 5, 1784, Jefferson, accompanied by Patsy, boarded the Ceres, which was bound for Cowes. He entrusted his younger daughters, Polly and Lucy— the two-year-old would die of whooping cough just a few months later—to the care of an aunt back in Virginia. Traversing the Atlantic did not stop him from piling up factoids. Every day at noon, he recorded in his account book numerous measurements, including latitude and longitude, the mileage since the previous day, the temperature, and wind direction. (Two decades later, President Jefferson would know whereof he spoke when he instructed his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to take “observations of latitude and longitude at all remarkable points on the [Missouri] river...with great pains and accuracy.”) And during the three-week journey to England, he also interviewed the owner of the ship, the Newburyport merchant Nathaniel Tracy, to complete his Massachusetts questionnaire. As he learned from Tracy, carpenters in the Bay State were now making about $7 a day, up from $3–$6 before the war.

Father and daughter arrived in Paris on August 6. On August 30, the forty-one-year-old diplomat met for the first time with his elders on the commission, Adams and Franklin, at the latter’s home in Passy. Revered by the French for his scientific knowledge and sophistication, Franklin would introduce Jefferson to the nation’s leading philosophes, artists, and writers. When Philadelphia’s polymath returned to America the following year, Jefferson became minister to France, a post he would hold until after the storming of the Bastille in 1789. “No one can replace him [Franklin],” Jefferson would repeatedly insist. “I am only his successor.” In 1787, his slave Sally Hemings escorted his eight-year-old daughter Polly from Virginia to Paris. His two girls would both attend the Abbaye Royale de Panthemont, an exclusive convent school, where, as Jefferson was assured, “not a word is ever spoken on the subject of religion.”

After a difficult first winter, when he was sidelined both by ill health and by the news of Lucy’s death, this “savage of the mountains of America,” as Jefferson described himself in 1785, began to acclimate to his new surroundings. Despite his lifelong antipathy toward big cities, which he later characterized as “pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man,” he couldn’t help but adore the architecture, sculpture, music, and art that now surrounded him. Jefferson was also fascinated by Paris’s technological marvels, such as its suspension bridges and gadgets; he enjoyed going to the Café Mécanique, where wine was served by dumbwaiters (as would later be the case in Monticello). The hot-air balloon enthusiast, who, before leaving Annapolis, had compiled a detailed list of recent French ascensions for a friend, rarely missed a chance to view a launch in the flesh. For the self-confessed bibliomaniac, the French capital’s ubiquitous bookstalls—such as those lining the Quai des Grands-Augustins—also proved irresistible. Though Jefferson forced himself to “submit to the rule of buying only at reasonable prices,” he ended up acquiring for himself about fifty feet of books a year, all of which he eventually had shipped back to Virginia. He also sent books back to several American friends—most notably, dozens on law and government to James Madison, just as his protégé was beginning to draft the Constitution. He soon found himself missing little about Virginia except for its factoids. “I thank you again and again,” he wrote in September 1785 to the Scottish physician James Currie, then in Richmond, “for the details it [your last letter] contains, these being precisely of the nature I would wish....But I can persuade nobody to believe that the small facts which they see passing daily under their eyes are precious to me at this distance; much more interesting to the heart than events of higher rank. . . . Continue then to give me facts, little facts.”

The following September, Jefferson was, as Dumas Malone has put it, “quite swept off his supposedly well-planted feet.” The new object of affection for the forty-three-year-old widower was Maria Cosway, a petite, blue-eyed, twenty-six-year-old artist, who was visiting from London where she lived with her husband, Richard Cosway, a successful portrait painter. The American ambassador first met the beautiful and musically talented Italian-born Maria—not only was she a composer, but she also played both the harpsichord and harp—on September 3, 1786, at the Halle au Blé, the domed Parisian grain market. Jefferson was accompanied by the American artist John Trumbull, who introduced him to both Cosways. Twenty years older than his wife, Richard Cosway was then in the personal employ of the Prince of Wales (later King George IV). With her family down on its luck after the death of her father, Maria had succumbed to her mother’s demand to marry the socialite with the deep pockets. The vapid and mercurial Cosway had little else to offer; as numerous contemporaries noted, he had “a monkey face” and couldn’t keep his hands off other women. Jefferson was instantly taken by Maria, whom he later called “the most superb thing on earth”; within minutes, he came up with an excuse to cancel his dinner engagement with the Duchess D’Anville. His long evening with the Cosways didn’t end until an impromptu harp concert in the wee hours at the home of the Bohemian composer Johann Baptist Krumpholtz. “When I came home . . . and looked back to the morning,” Jefferson later wrote Maria of their first meeting, “it seemed to have been a month gone.”

For the next two weeks, Jefferson and Maria were inseparable. Either alone or in the company of others such as Maria’s husband, Trumbull, William Short (Jefferson’s personal secretary), or his daughter Patsy, the mutually infatuated couple played tourist, heading to one scenic attraction after another. They gallivanted to the Royal Library (today the Bibliothèque Nationale), the Louvre, Versailles, and the Théâtre-Italien, as well as to the hills along the Seine. Whether Jefferson and Maria ever consummated their love has been the source of lively debate among Jefferson scholars. While the fragmentary evidence points to little but the likelihood that they both harbored fantasies about sexual union, physical intimacy is not out of the question; after all, given her marriage of convenience, Maria felt as lonely as Jefferson, as he probably picked up quickly, and their outings took place in the city that was then widely considered the world’s capital of illicit love. (Jefferson’s secretary, Short, would manage to have a couple of affairs during his Parisian sojourn, including one with the young wife of Duc de La Rochefoucauld.) On September 18, Jefferson severely injured his wrist while strolling with Maria near the Champs-Élysées. Due to the intense pain, he retreated to his home for a few weeks; and though Maria intended to visit, she could never squirm away from her husband. On Friday, October 6, a still ailing Jefferson accompanied the Cosways to the town of St. Denis, where they boarded a carriage for the trip back to London.

Over the next few days, Jefferson wrote out with his left hand what Julian Boyd, an editor of his collected papers, has called “one of the notable love letters in the English language.” Its form was distinctly Jeffersonian. The man who had difficulty romancing women with words (as opposed to music) declared his love in a curious 4,600-word missive, which pivots around a philosophical dialogue between his “Head” and his “Heart.” As with his clumsy second proposal to Burwell, an anxious Jefferson once again pretended as if the woman of his dreams did not exist. Rather than expressing his feelings directly to Maria, he dramatized his own internal conflict. As Jefferson framed the imaginary debate, at the same time as his rational side was chastising him as “the most incorrigible of all the beings that ever sinned” for the decision to spend so much time with her, his emotional side was “rent into fragments by the force of my grief.” While “Head” would have the last word, the insistence by “Heart” that he give up trying to see Maria again and turn his attention back to his male friends such as the brilliant French mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet seemed to carry the day.

All this philosophizing left Maria thoroughly confused, leading her to compose, as Boyd has put it, “a baffled . . . response.” “How I wish I could answer,” she began her first letter from London on October 30, “the Dialogue!” She reported that her heart was simultaneously both “mute” and “ready to burst with all the variety of sentiments, which a very feeling one is capable of.” Not knowing what to say, she lapsed into a friendly but matter-of-fact message in her native Italian. Whatever romantic longings she had harbored for Jefferson, his bewildering words had extinguished. She returned to Paris in late August 1787 without her husband, but much to Jefferson’s disappointment, he didn’t get to spend much time with her. “From the mere effect of chance,” Jefferson wrote to Trumbull on November 13, in what was perhaps an attempt to rationalize his hurt feelings, “she has happened to be from home several times when I have called her, and I, when she has called on me. I hope for better luck hereafter.” It never came. She left Paris a month later, and they never saw each other again. The intermittent epistolary friendship, however, would continue for the rest of their lives. Maria eventually did leave her husband to start a convent school outside of Milan, where she died at the age of seventy-eight in 1838.

Just as the romance with Maria was cooling off, another woman marched into his life. On July 15, 1787, when Sally Hemings arrived with Polly at his Paris abode, the Hotel de Langeac, she was just fourteen. His slave was a half sister of his late wife; described by contemporaries as “an industrious and orderly creature in her behavior,” the light-skinned and attractive Sally, with her long, straight hair, also bore a clear physical resemblance to Martha Wayles. She was the product of the union between John Wayles and Betty Hemings, a slave who became his concubine after the death of his third wife. Upon the death of John Wayles in 1773, Jefferson inherited the infant Sally. In France, she served as a lady’s maid to his two daughters; Jefferson encouraged her to learn French and generously provided for her. According to his account books, he spent nearly two hundred francs in April 1789 on her clothes—a considerable amount, given that gloves cost only two francs.

The allegation that Jefferson engaged in a long-term sexual relationship with Sally, which may have begun as early as 1788, was first made public by the Scottish-born journalist James Callender, in a series of articles written for the Richmond Recorder in the fall of 1802. “It is well known that the man,” Callender wrote of the president, “whom it delighteth the people to honor, keeps and for many years past has kept, as his concubine, one of his slaves. Her name is SALLY.” Callender’s reporting never carried much weight because he was known to be irascible and unstable—he died of an apparent suicide a year later—and he had an axe to grind. A former political ally of Jefferson’s, Callender was miffed because the president had not appointed him postmaster in Richmond, as he had expected. In 1868, Martha’s son, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, told biographer Henry Randall that Jefferson’s nephew, Peter Carr, fathered Sally’s children, a claim that most historians accepted for more than a century. But the entire landscape changed dramatically in 1997 with the release of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy by Annette Gordon-Reed, currently a professor of history at Harvard. Examining a wealth of sources, including Jefferson’s Farm Book, in which he recorded the births of Sally’s six children and detailed testimonials by two of them, Gordon-Reed argued that Jefferson was likely the father of all six. (In contrast to most of his other slaves, at Jefferson’s behest, Sally, as well as her four children who reached adulthood, all lived in freedom after his death.) In 1998, Nature published the results of a DNA test that revealed a match between the last child, Eston Hemings, and the male Jefferson line, but not with the male Carr line. Today Gordon-Reed’s position represents the scholarly consensus, although some skeptics continue to insist on alternative explanations.

In the two centuries between Callender’s explosive articles and Gordon-Reed’s scholarly volumes—her follow-up study, the Pulitzer Prize–winning The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, appeared in 2008—most historians, when they deigned to enter into this debate at all, cited their own idealized view of Jefferson as “proof” that the Federalist journalist must have been slinging mud. “[The charges],” asserted Dumas Malone, “are distinctly out of character, being virtually unthinkable in a man of Jefferson’s moral standards and habitual conduct.” Though it’s impossible to know with absolute certainty, as Gordon-Reed concedes, whether Jefferson slept with his slave even once, the flip side of this long-standing assumption seems much more plausible. The choice of Sally Hemings as a mistress is entirely consistent with Jefferson’s character disorder. For obsessives, in intimate relationships, as in everything else, control is the be-all and end-all; a genuine partnership with mutual give-and-take is anathema. In Sally, a woman thirty years his junior, whom he happened to own, Jefferson might well have found just what he was after. That was what Aaron Burr concluded, at least according to the late Gore Vidal. In his 1973 historical novel, Burr, the man who served as vice president during Jefferson’s first term describes the submissive Sally as “exactly what Jefferson wanted a wife to be.”

*

“Never did a prisoner,” wrote the sixty-five-year-old Jefferson a couple of days before the end of his second term, “feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power.” No longer weighed down by pressing political responsibilities, the self-described “hermit of Monticello” began “enjoying a species of happiness that I never before knew, that of doing whatever hits the humor of the moment.” For Jefferson, spontaneous fun meant immersion in one project after another designed to bring more order into his world. Some would be of minimal significance to posterity, but others of considerable. While he may not have been our most productive ex-president—a designation often accorded to Jimmy Carter—he may well have been our most industrious, most neat, and most devoted to the cause of organization.

Gardening was high on his agenda. For years, Jefferson had collected seeds from all over the world, which he stored in “little phials, labeled and hung on little hooks . . . in the neatest order,” according to one visitor to Monticello, and he was eager to see what he could grow. A week after returning home from Washington, he started a massive eight-column “Kalendar” in his Garden Book, in which he tracked the hundreds of vegetables that he planted that spring and summer. (Though no subsequent “Kalendar” would be quite as long, Jefferson would compile one every year until 1825.) Applying his characteristic thoroughness, he kept experimenting and refining his methods. When the Roman broccoli which he had first sowed on April 20, 1809, “failed nearly,” the recently retired president didn’t give up; he tried again on May 30 and June 3, and eventually managed to transplant a total of 135 broccoli plants on July 10. “Under a total want of demand except for our family table,” Jefferson wrote a friend in 1811, “I am still devoted to the garden. But though an old man, I am but a young gardener.” He also laid out shrubs and filled in the flower beds that surrounded his house. While Sally’s nephew, his slave Wormley, did the digging, Jefferson trailed behind with his measuring line and pruning knife in order to keep the rows properly aligned. In so doing, Jefferson was paying homage to his obsessive father, who had organized Shadwell’s vegetable and flower gardens in numbered beds ordered in rows designated by letters.

In March 1815, Jefferson began labeling and organizing his books one last time. Six months earlier, after hearing that the Brits had burned down the original Library of Congress, the deeply indebted farmer had offered to sell his entire collection so that the feds could start anew. By early 1815, the deal was done; Jefferson ended up receiving $23,950 for the 6,047 volumes that, according to his measurements, occupied 855.39 square feet of wall space in bookcases that comprised a total of 676 cubic feet. While Jefferson had already updated his catalog, which subdivided Francis Bacon’s three broad categories into forty-four chapters (subjects)—under Memory, for example, Civil History was chapter 1—he still needed to do some checking and rechecking. “I am now employing as many hours of every day as my strength will permit,” he wrote to President Madison on March 23, “in arranging the books and putting every one in its place on the shelves and shall have them numbered correspondently.” Even with the help of three grandchildren, the operation would take two months. For each book, Jefferson affixed a label that indicated both the chapter to which it belonged and its place on the shelf; in his bookcases, Jefferson had arranged the volumes both by subject and by size—the clunky folios, for example, were stacked together at the bottom. Hoping to prevent Congress from messing up his complex organizational scheme, for which he would later be feted as the “Father of American Librarianship,” Jefferson used his own shelves as shipping crates. However, much to his horror, George Watterson, the Librarian of Congress, while preserving his chapter divisions, decided to organize his books alphabetically rather than by subject. Upon receiving his personal copy of Watterson’s printed catalog, an enraged Jefferson took out his pen and rearranged all his books into their original order. While Watterson did not clean up his mess, several years later, Jefferson instructed his personal secretary, Nicholas Trist, to transform his marked-up catalog into a new manuscript containing his original scheme.

This compulsive reorganizer also would not hesitate to deface the Western world’s most hallowed texts—the Gospels. In the summer of 1820, Jefferson vented his pique at organized religion by slicing and dicing eight Bibles—two each in Greek, Latin, French, and English—with a razor blade. Pasting the shreds together, he created a new book with parallel passages in the four languages, which he called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. This biography of Christ consisted of nothing but the texts written by the Evangelists as rearranged by Jefferson. Though his political opponents often portrayed him as an atheist, Jefferson was a devout Christian. In 1822, he would summarize his core beliefs in the following list:

- That there is only one God, and he [is] all perfect.

- That there is a future state of rewards and punishments.

- That to love God with all thy heart and thy neighbor as thyself is thesum of religion.

But this creature of the Enlightenment could not stomach any counterfactual mumbo jumbo. “The Jefferson Bible,” which he dubbed his “wee little book,” excises all supernatural events, removing both the Annunciation and the Resurrection and every angel. While Jefferson discussed his faith with select friends and family members, he appears not to have shown this book to anyone. He viewed religion as he did most human activities—as a means not to seek inter-personal connection, but to express personal freedom. “I am of a sect by myself,” he wrote in 1819, “as far as I know.”

Jefferson’s final retirement project has been his most enduring. Despite minor ailments like rheumatism, the still fit former president would remain in good enough health to continue his daily horseback rides until the last few weeks of his life. And in early 1819, he took on a new challenge, that of rector of a new citadel to learning chartered by the Virginia state legislature. “While you have been,” Virginia senator James Barbour wrote to him in January 1825, two months before the University of Virginia held its first classes, “the ablest champion of the rights and happiness of your own generation, you have generously devoted the evening of your life to generations yet unborn.” Eager to instill in America’s youth “the precepts of virtue and order,” Jefferson micromanaged every detail of his new creation. He designed the campus, placing at the center a large domed building, which housed the library—rather than a church—to “give it unity.” He modeled the Rotunda on Andrea Palladio’s Pantheon; on its two sides were several two-story pavilions alternating with one-story dormitories, all of which he numbered in his architectural drawings. He also supervised the recruiting of its first five faculty members from Europe. Throughout the summer of 1824, he spent four hours a day compiling the catalog for its library (his final tally of 6,860 volumes divided into forty-two chapters, which he estimated would cost $24,076, mirrors the numbers for the library that he had sold to the feds a decade earlier). And Jefferson also devised all the university’s rules and regulations, specifying, for example, both that professors were to teach only six hours a week and that the school day was to run from 7:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. In order not to intrude on students, the domineering and controlling leader with the fervent antiauthoritarian streak eschewed a fixed curriculum in favor of electives. However, those who selected classes on law and government would be required to tackle his reading list, at the top of which stood the Declaration of Independence, the Federalist Papers, and Washington’s inaugural and farewell addresses.

Shortly after Jefferson’s death on July 4, 1826, a family member found in a secret drawer in his private cabinet a series of neatly labeled envelopes, which contained locks of hair and other little mementos originally belonging to his wife, Martha, and to each of the six children he had fathered with her. “They were all arranged in perfect order,” observed biographer Henry Randall, “and the envelopes indicated their frequent handling.” For this inveterate collector, as with his books, so with his family members—to classify and arrange was to love.

Excerpted from "America's Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built A Nation" by Joshua Kendall. Published by Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group Inc. Copyright 2013 by Joshua Kendall. Reprinted with permission of the author and publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares