There's no better way to indicate you've learned from your mistakes, it seems, than to gaudily acknowledge them in the most public way possible. Recently, several brands have taken to the airwaves to tell viewers that they've learned from their missteps. None of these missteps were as grave as the racist statements Paula Deen had to apologize for recently -- but then, the apologies don't seem nearly as deeply felt as her weepy, complicated video messages. The brands are just trying to dictate to potential customers that things are great.

The department store JCPenney, which has seen collapsing sales amid a revised policy ending short-term discounts, has been broadcasting an ad indicating "Some changes you liked, and some you didn't. But what matters with mistakes is what you learn." The discounts are back, but the ad puts an odd gloss on JCPenney's difficult period -- customers have flat-out rejected the store in general, and none of the changes were met with approval.

Delta Airlines recently edged up to an apology for disgruntled passengers, acknowledging the challenges of "an unpredictable industry" (including the vacillations of oil prices), but the statement came closer to apologia than actual admission of guilt.

And, recently, the Atlantic City casino Revel has announced -- with an apologetic ad playing on local television stations -- that it's sorry for launching with a limited focus on gambling and a ban on indoor smoking. Now you can smoke inside and play slots for free (or free-ish; with reimbursement parceled out on a Revel Card).

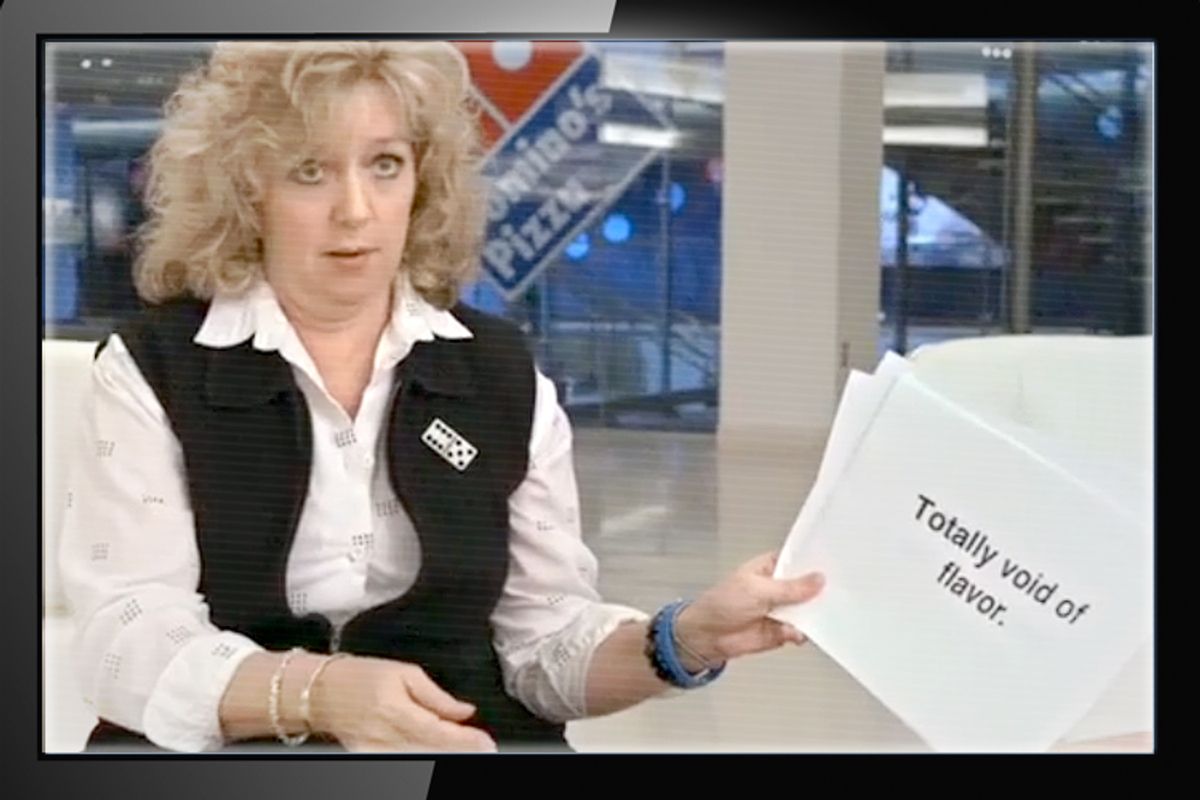

These apologies have the patina of sorriness, but they aren't exactly apologetic. They recall Domino's "Pizza Turnaround" ad, a classic of the form, in which Domino's bragged about how much better Domino's was tasting now -- um, sorry about the bad pizza before!

"This is the one place that I think a little humor can work," said Lauren Bloom, the author of "Art of the Apology: How to Apologize Effectively to Practically Anyone," whose revised edition is forthcoming. "Often I'm very skeptical at humor in an apology -- people think they're laughing with the person they're apologizing to, but they're laughing at them." She cited, though, an ad that Johnson & Johnson put on the Internet after o.b. tampons went off the shelves, featuring a personalized song of apology to any o.b. user who entered her name online.

"Netflix did a reasonable job of saying [it was sorry for changing its service, in an email sent to subscribers]," said Bloom, "but they could've gotten away with a video."

Obviously, the calculus changes when the thing a company is apologizing for is hazardous or deadly, not just annoying. Tony Hayward, the CEO of British Petroleum, apologized for the oil spill in an advertisement and claimed it was his company's responsibility to clean the Gulf, though as Aaron Lazare, the author of "On Apology," pointed out, "They forgot to apologize for killing 12 people. You don't want to promise too much but you want to acknowledge what you did."

Lazare, the former chancellor of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, said that a unilateral apology to a client base had to clear a far higher bar than one person's face-to-face apology to another, which can begin a spontaneous discussion. "If I apologize to you in person, I have to be ready for you to tell me I'm up the creek. A public apology unilaterally puts the burden on you to get it right the first time. Most apologies are awful or shallow or they become offensive."

"A good apology," Lazare said, "convinces someone you'll make up for it or you'll change." A slowly parceled out reimbursement for slot playing (which isn't explicitly laid out in Revel's advertising) or elaborate justifications for why delays and high ticket prices are part of Delta doing its very best, feel less apologetic than self-justifying.

The mere fact of buying an ad to apologize -- unless it's explicitly and clearly an explication of everything done wrong and how it will improve, like United Airlines' CEO's 2000 apology for a disruption in its grid leading to delays -- feels chilly, corporate and demanding. No one person is apologizing on behalf of JCPenney or Delta, unless you count the voice-over artist (Donald Sutherland for Delta!). "When you're making a video, unless it's a CEO in front of a blank wall, you're going to get something scripted and polished," said Bloom.

"Saying, 'We're aware of what happened and we'll work to improve,' is more humble and honest than saying, 'We've improved,'" said Lazare. But simply indicating striving isn't enough to get people through the door. Who'd want to shop at a department store that was slowly transitioning toward being better?

Public figures like Deen can sink into oblivion after apologizing and wait for the public to forgive them -- it's a tack taken by two New York-based comeback kids, Anthony Weiner and Eliot Spitzer, both of whom are running for office this year after late-2000s sex scandals. But businesses have to open the door every day; JCPenney can't wait around for the public to make up its mind. Hence the charm offensive. And as slick and impersonal as the ads feel, the proof will be in the pudding; they serve merely to signpost changes or recommitment to goals that the public will hopefully appreciate. The best thing an apology ad can do is be memorable enough to get the customer in the door and forgettable enough to vanish into the ether once a company's back on its feet. "I think Americans are amazingly forgiving people," said Bloom. "If people like a company, they'll be back."

Shares