“There is a time for reciting poems,” Roberto Bolaño wrote in The Savage Detectives, “and a time for fists.” And now, with the appearance of his collected poetry, The Unknown University, presented in a bilingual edition translated by Laura Healy and handsomely published by New Directions, we are getting to the end of the Bolaño canon (in fact, we may be at the end), with its short stories, brief novels, and the two long masterpieces, The Savage Detectives and 2666, as well as an enlightening volume of critical pieces, speeches and interviews entitled Between Parentheses. What remains to be written is a comprehensive biography of the man. And I suspect we will be no more the wiser. Though not as shadowy as, say, B. Traven, elusive author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, who vanished into a fog of multiple identities, Bolaño’s life is in comparison a gumbo of tall tales, rumor, truth and consequence, some created by him (perhaps because we identify some of his characters—and voices—a little too closely with their creator), others encouraged by a public hungry for a romantic hero. Or, to borrow the title of a smaller collection of his poems, romantic dog.

“There is a time for reciting poems,” Roberto Bolaño wrote in The Savage Detectives, “and a time for fists.” And now, with the appearance of his collected poetry, The Unknown University, presented in a bilingual edition translated by Laura Healy and handsomely published by New Directions, we are getting to the end of the Bolaño canon (in fact, we may be at the end), with its short stories, brief novels, and the two long masterpieces, The Savage Detectives and 2666, as well as an enlightening volume of critical pieces, speeches and interviews entitled Between Parentheses. What remains to be written is a comprehensive biography of the man. And I suspect we will be no more the wiser. Though not as shadowy as, say, B. Traven, elusive author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, who vanished into a fog of multiple identities, Bolaño’s life is in comparison a gumbo of tall tales, rumor, truth and consequence, some created by him (perhaps because we identify some of his characters—and voices—a little too closely with their creator), others encouraged by a public hungry for a romantic hero. Or, to borrow the title of a smaller collection of his poems, romantic dog.

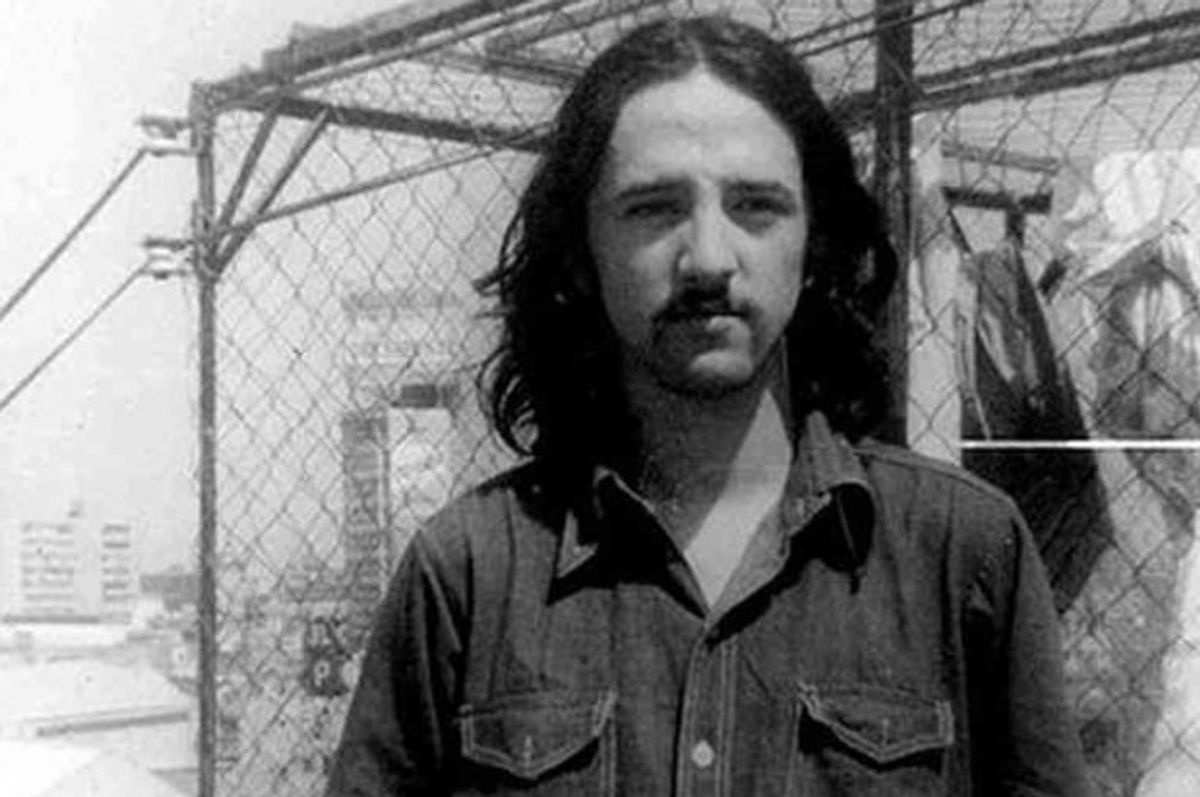

We know that Roberto Bolaño was born in 1953 and died fifty years later of liver disease. Was he indeed incarcerated by the Chilean government at the time of the 1973 coup? Had he been a heroin addict? Does it matter? Just as Bob Dylan (a name I’ve linked to Bolaño in previous reviews, for their works bear a certain mythmaking similarity) has left us in doubt about what has really happened in his life—there’s nothing like silence and cryptic wiseass answers to give buoyancy to myth—Bolaño turns us back to his books and his poems every time. Though many of his works seem, on the surface, autobiographical, they are best read for what they are—variations on his world, in which his role as both creator and, of course, player wreaks havoc with reality, for he stands both inside and outside his own work. Which is the loneliest place for any writer to be.

The present volume collects all of Bolaño’s poetry, which also includes prose poems of sometimes substantial length. The volume entitled Antwerp, separately published earlier by New Directions, is considered part of his poetic works, and is included in this collection. The latest and most comprehensive collection is made up of three parts, each collecting several smaller gatherings of his poetry. Though a poetry collection is sometimes considered something to visit now and again, I found, reading this straight through, many pages each day, to be akin to reading one of his longer novels. There’s a life electric here, full of ghosts and demons and killers and whores, with room for lovers and sons, as well, and the tender thoughts of a father fading fast.

His poetry—not unexpectedly of uneven quality, especially when it comes to the more youthful efforts—is all of a piece with this, and like his fiction is consistent in an inconsistent world peopled by wandering putas, thieves, murderers, the innocent, and, mostly, the damned. The innocent often end up butchered in a Mexican desert; the evil sit in a bar outside Mexico City, knife in pocket, all jump and trouble. His world cozies up to Malcolm Lowry’s in Under the Volcano, whose Quauhnahuac is like a Hernando’s Hideaway of the evil eye and the homicidal smile. No one may know your name or your face, but it doesn’t stop them from doing you in. When innocence meets experience, in both Lowry and Bolaño, innocence gets the chop. Something’s pounding my heart, boss, is the first line of his poem “The South American.”

The tall pale guy

turned back.

We’re in the realm of film noir here, as we are in so much of Bolaño. Men step out of shadows; others drive away, leaving something in the roadway. Guns are pulled, knives unsheathed, and when people wake it’s often into a fresh nightmare.

Between one point and the other I see only

my own face

entering and leaving the mirror

over and over.

Like in a horror film.

Know what I mean?

The ones we call psychological thrillers.

This comes in a late poem, “Self-Portrait,” found in the section entitled “A Happy Ending,” and subtitled Finally the poet as a child and the child of the poet.

Threat and the burgeoning clouds of violence are never very off in this universe. The poet is hardly the occupant of the fabled ivory tower, penning his verses and contemplating his dreams amid the exquisite drapery of academic honors and an adoring public. This is a guy who wanders the streets, who knows poverty, who’s slept with hookers, who’s consorted with the masters of the lower depths. As he writes in the poem, “The Taoist Blues of Valle Hebrón Hospital” (which could almost be a mid-Sixties Dylan title),

That’s how you and I became

Sleuths of our memory.

And traveled, like Latin American detectives,

Over the dusty streets of the continent

Looking for the assassin.

But we only found

Empty shop windows, ambiguous manifestations

Of truth.

Famously dyslexic, his relationship with language is like that between a prizefighter and the last guy who knocked him out after three rounds: always getting back on his feet to get the better of his opponent. Best known for his monumental novels The Savage Detectives and 2666, Bolaño considered poetry his ideal art form, until, according to his editor and friend Jorge Herralde, it came down to the brutal truth that he had a family to maintain. The pennies one earns from the publication now and again of a poem—if you’re lucky, that is—was simply not enough. Like many writers who dive into their profession feet first, Bolaño wrote to support his wife and children, especially in light of his failing health of his last years. He wanted 2666 to be published not in one volume but as five separate books, the better to increase his royalty income. The poetry, however, came from a very different necessity.

Writing poetry in the land of idiots.

Writing with my son on my knee.

Writing until night falls

With the thunder of a thousand demons.

The demons who will carry me to hell,

but writing.

As a novelist, Bolaño is constantly talking to himself: telling and retelling events from his life, or a life he imagines he might have had; events closed to us, that profoundly came to define him. His stories, whether stand-alone or as part of his novels, are like armored vehicles: they make noise, you turn to look, you may even admire them, but what’s inside is ultimately hidden from you; they belong to a deeper, more private species of myth. Characters straight out of genre fiction wander into all of his work: outlaws and outcasts, detectives and murderers, whores and pimps, junkies and thieves. He was as well read in pulp fiction as he was in the classics. He loved Proust, but he also was an avid reader of James Ellroy and Philip K. Dick, and this mix permeates his work both as prose-writer and poet.

Looked at objectively, his prose has a hasty, sometimes sloppy aspect to it, instead of the polished-to-a-fault writing of too many “literary” novelists. He’s more at home with the colloquial than with the academic, and his work is all the better for it. He has more in common with the French writers of his generation who combine genre with the literary—Manchette, Modiano, Belletto, Echenoz, and several others—who find it difficult here in the US to gain a foothold, where people like their genre writing straight up and adhering to expectations, the cozy assumptions created by a publishing industry that doles out title after title, all of them following a similar train of thought, a parade of set pieces we’ve seen all too often before.

Some who’ve read 2666 have complained that the famous The Part About the Crimes is too brutal to take. Yet so was the reality behind the fiction. And so is police work, especially when it comes to the monotony of serial killing. It’s one body after another, harvested from the arid Mexican soil like so many crops gone to hell. To prettify it, to make it “literary,” would be to deny the truth of it. Bolaño gives us the world as he knows it—the flash of a blade, the cruel betrayal of a woman, the underbelly (figurative and literal) of the public baths in Mexican Manifesto, one of the many prose pieces collected here (and recently published in the New Yorker). It all serves to show that great fiction isn’t there to make us feel good; there are far easier ways to do this. Open your liquor cabinet and have a go. Bolaño is the Kafkan axe for the frozen sea within us.

Shares