There was a time when rank iniquity got a bum rap on television, when serial killers, gangsters, dope dealers, corrupt cops and the like were routinely portrayed in a negative light. (Advertising executives, too, for that matter.) They turned up in popular entertainment regularly enough, but as villains and foils, with a simple if unenviable mission in life: to go down to ignominious defeat, preferably sniveling, vanquished by our heroes as the credits rolled.

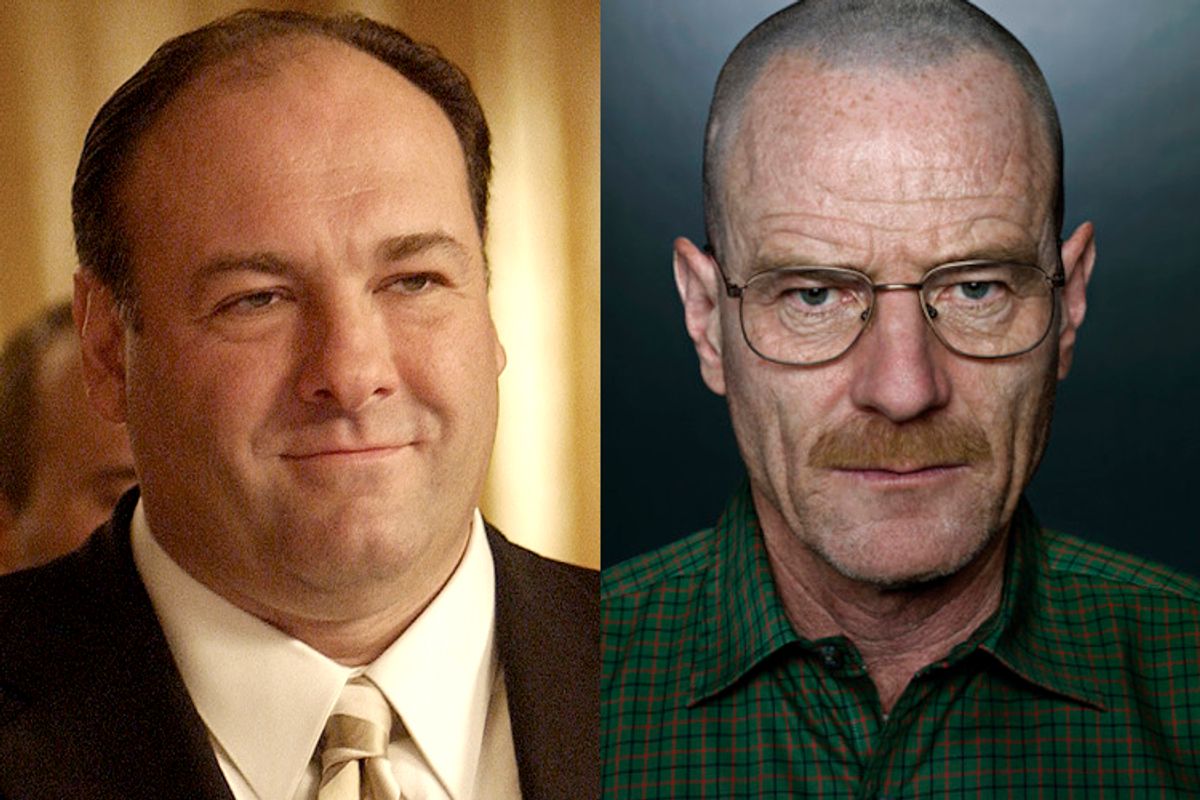

The story of how the bad guys won, how Tony Soprano, Vik Mackie, Walter White, et al., bullied their way onto our plasma screens, is the subject of "Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution," Brett Martin’s keenly observed examination of what he terms television’s Third Golden Age.

The book’s title is a reference not only to the tormented protagonists of such groundbreaking cable series as "The Sopranos," "The Wire," "The Shield," "Six Feet Under," "Deadwood," "Mad Men" and "Breaking Bad" — but to their creators, guys autocratic, combative, insecure, egomaniacal and sometimes plain nasty enough to transform a fundamentally commercial medium into a canvas for high art. “It was necessary for me to always take the point of view that I was obligated to no one and nothing,” misanthropic "Sopranos" capo David Chase tells the author at one point. Or as Steven Bochco, the co-creator of "Hill Street Blues" and "NYPD Blue" (direct antecedents of the contemporary cable drama), allows, “I probably did come off as an arrogant a--hole. But you had to be. We were bucking a system.”

Passionate and uncompromising, these men managed to secure for themselves a level of poetic license that would have been unthinkable in previous decades, helping to codify the role of the all-powerful showrunner — which is to a television drama, and sometimes a network’s brand identity and bottom line, what a toddler is to a mud pie.

“This isn’t publishing some lunatic’s novel or letting him direct a movie,” one unnamed source tells Martin. “This is handing a lunatic a division of General Motors.”

The author secured the cooperation of all of his primary subjects, with the exception of "Mad Men's" Matthew Weiner, as well as many of their colleagues, and "Difficult Men" offers readers a rare glimpse inside the writers rooms — “hotbeds of emotional turmoil and transference,” Martin writes — where these avidly watched serials came to life.

Among a number of choice anecdotes, Martin recounts Chase’s firing of a brilliant young protégé, writer Matthew Kessler (who would go on to create "Damages"), a rub-out performed with such magnificent sangfroid it would make Paulie Walnuts proud. Weiner’s management style is described as so abrasive that “it became routine for writers, leaving meetings on their script, to hit the bathroom in order to let the tears subside.” And "Deadwood" creator and "Hill Street Blues" vet David Milch, who has battled addictions to alcohol and heroin, is variously described by colleagues as a genius, a wildman, a bully, a father figure and “Caligula.”

These productions took a toll on the performers as well. In 2002, as the pressure of carrying a major series became ever more acute, James Gandolfini disappeared from the "Sopranos" set for four worrisome days while the production ground to a halt. "The Wire's" Michael K. Williams (Omar) was evicted for stiffing his landlord as he became the show’s most popular figure. Martin also notes the downfall of Chris Albrecht, HBO’s brilliant programming chief, who was fired at the height of his success after a domestic abuse incident.

Such turmoil aside, while "Difficult Men" will inevitably be compared to "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," Peter Biskind’s rollicking look at the creative (and pharmacological) revolution that swept Hollywood in the 1970s, Martin is less interested in documenting behind-the-scenes melodrama than in tracing a wider story arc, the fortuitous confluence of factors that brought about our ongoing television renaissance.

On that day in 1999 when a flock of wild ducks took a bath in Tony Soprano’s swimming pool, the chickens were already coming home to roost for the network model: Cable had achieved wide penetration, and the DVD market was gathering steam; TiVo was set to liberate viewers from the tyranny of the program schedule, and Netflix was beginning its first experiments with streaming. All these changes benefited premium cable, where a season of television could be shorter (13 episodes rather than 22) and more densely plotted, with multiple story lines playing out over elaborate tableaux. Meanwhile, the lack of commercials meant the shows could tackle darker, more sophisticated themes. And perhaps most important, the reliance on subscription or carriage fees provided a rationale for HBO and later Showtime, FX, AMC and others to roll the dice on behalf of shows that would draw smaller but intensely devoted audiences.

It all added up to an unprecedented period of “creative fecundity,” as Martin puts it in one characteristically thoughtful passage, “that comes with a genuine business and technological upheaval — that is, from people not knowing what the hell to do and thus being willing to try anything.”

Shares