It seems not all black people are created equal. We are as diverse as our myriad opinions.

Before President Obama’s speech last Friday addressing the disheartening verdict in George Zimmerman’s trial for the murder of teenager Trayvon Martin, the African American chattering classes offered an array of advice and admonishments to the nation’s first black president.

Janet Langhart Cohen, in an op-ed for the Washington Post, called for the president to break his silence on race. She acknowledged the fine line he has walked, being the “first,” and his responsibility to all communities, not just African Americans — but expressed a hope that “once he entered his second term, Obama would be liberated from the racial harness that politics forced him to wear.” She grappled with the underlying disparities in criminal justice and misguided social policy that leads, all too often, to the kind of tragic end for which Trayvon Martin has now become a martyr.

“During this period of self-imposed silence,” Langhart Cohen writes, “we have watched our criminal laws become racialized and our race criminalized. Blacks continue to be faced with punishing unfairness and inequalities. Soaring rates of unemployment, discriminatory drug laws, disproportionate prison sentences…stop-and-frisk policies and “accidental” shootings of unarmed black men by the police…We’re told to stop complaining, to get over it.”

In her opinion, the president needed to speak about race, and to do so forcefully and unapologetically. But even her colleagues disagreed.

Eugene Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize winning columnist for the Post, argued that a national conversation on race was necessary, but that President Obama was the wrong person to lead it. Robinson noted that whenever Obama had tried to talk about race in the past (e.g., in response to Professor Henry Louis Gates’ arrest for trespassing in his own home) it had been seen as threatening. Talking heads and politicians on the conservative right conveniently distorted and attacked what they perceived to be yet another example of an angry black man.

Though Robinson was correct in his observations, his conclusion was flawed. The truth is President Obama should never shy away from a topic simply because it angers Republicans or neo-Confederate Tea Party activists. As Martin Luther King, Jr. so eloquently stated, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” And for as long as the American experiment has existed, race and racism have remained matters of challenge and controversy.

Likewise, Langhart Cohen’s insights failed to adequately acknowledge the fact that disparate racial outcomes and racialized criminality of young black males existed long before Obama’s tenure. As such, though we may look to him for leadership on matters of civil rights, he is not a civil rights leader. President Obama is leader of the free world. And when he speaks, his message transcends the constructs of race, class and even American identity.

In the aftermath of the president’s comments, distractors and dissenters were eager to make their presence known.

Rich Benjamin, author and contributor to Salon, criticized the president for being too safe, too idealistic and not angry enough. The author asked if Attorney General Eric Holder was President Obama’s “inner ni**er” – arguing that Holder has been an aggressive spokesperson on matters of racial inequality. Benjamin tried to explain his intent by naively comparing his use of the racially charged term to someone referring to an adult’s “inner child.” The author seemed blissfully unaware that “child” and “ni**er” – neither actually nor for purposes of insult — shared any context historically or implicitly.

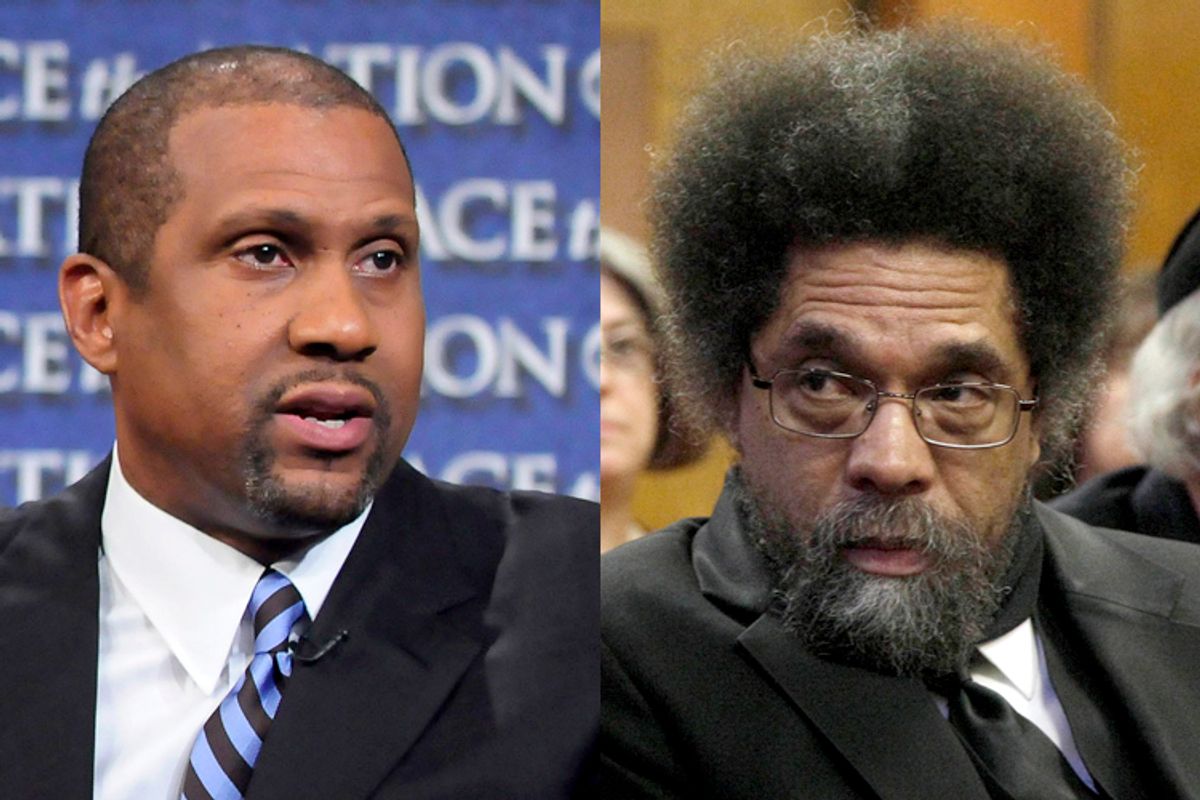

Tavis Smiley, the African American television and radio personality, displayed an equally baffling expression of cognitive dissonance, when he claimed on NBC’s "Meet the Press," “I appreciate and applaud the fact that the president did finally show up. But…he was pushed to that podium.” Smiley then went on to suggest that Truman and Johnson had somehow done more for racial progress than President Obama — the first African American president whose very existence is, perhaps, the culmination of both all racial struggle and all racial progress the nation has ever known.

Dr. Cornel West followed Smiley’s lead, saying in a televised interview for Democracy Now, "[Obama] hasn’t said a word until now — five years in office and can’t say a word about a 'new Jim Crow.' …Obama and [Attorney General Eric] Holder — will they come through at the federal level for Trayvon Martin? We hope so — [but] don’t hold your breath. There’s going to be many people who say, 'We see this president is not serious about the criminalizing of poor people.'"

Inherent in many of these critiques is a latent presumption that somehow these critics’ “blackness” is more authentic than Obama’s. That somehow the president has something to prove, and that only a constant reiteration of his positions on matters of race and injustice can qualify his authenticity. This is a fatal flaw in understanding what it means to be both black and president in America. It presumes that the two should be at war with one another: the presidential Obama versus his black self. That perspective isn’t so different from what is expressed by far-right wingnuts who demand Obama’s birth certificate.

Smiley and West seem to be asking to see the president’s “black card,” and in so doing, miss the point: that this Harvard-educated, first African American president has used his global platform to say what matters most, that if he “had a son, he’d look like Trayvon” and that “Trayvon Martin could have been me.”

The progressive activism, policy initiatives and proposals that can grow from these simple admissions are immeasurable. The power of President Obama’s words, and the dignity they provide to the lives of otherwise ignored and forgotten young black males, is not to be undermined or underestimated. What his comments beautifully convey is a reality of African American life hardly discussed or acknowledged outside of the black community. Yet the responses to Obama voicing such a rarely articulated point of view are in their own way equally important. These reflect the diversity of the black American experience – socially, culturally and intellectually.

If the failure to understand the humanity of young black males lies at the heart of both why George Zimmerman murdered an innocent child and was then acquitted by a mostly-white jury – then the only way to combat that violent ignorance is to express and embrace our humanity all the more. In our outrage, our questioning, our disappointments, and in our truths. In reconciliation of our differences; in our pride, our fear and most of all, in our understanding.

Shares