Late Monday evening, cellphone users all over southern California received a disturbing message – an AMBER alert issued for 16 year-old Hannah Anderson and her 8 year-old brother Ethan. Police had earlier discovered the body of the Anderson's mother and another child, and had identified James Lee DiMaggio as a suspect in the death of the two victims and the abduction of the siblings.

In a horrific case of potential kidnapping, time is of the essence. And so the state of California issued the first of a new kind of AMBER alert. Previously, cellphone users had to sign up to receive the alerts, but on Monday, they learned they were automatically signed up -- and will remain so unless they opt out. The new Wireless Emergency Alerts can now potentially reach "97% of the 300 million-plus active cellphones in the United States." They can reach tens of thousands of phones at once, even phones set to silent.

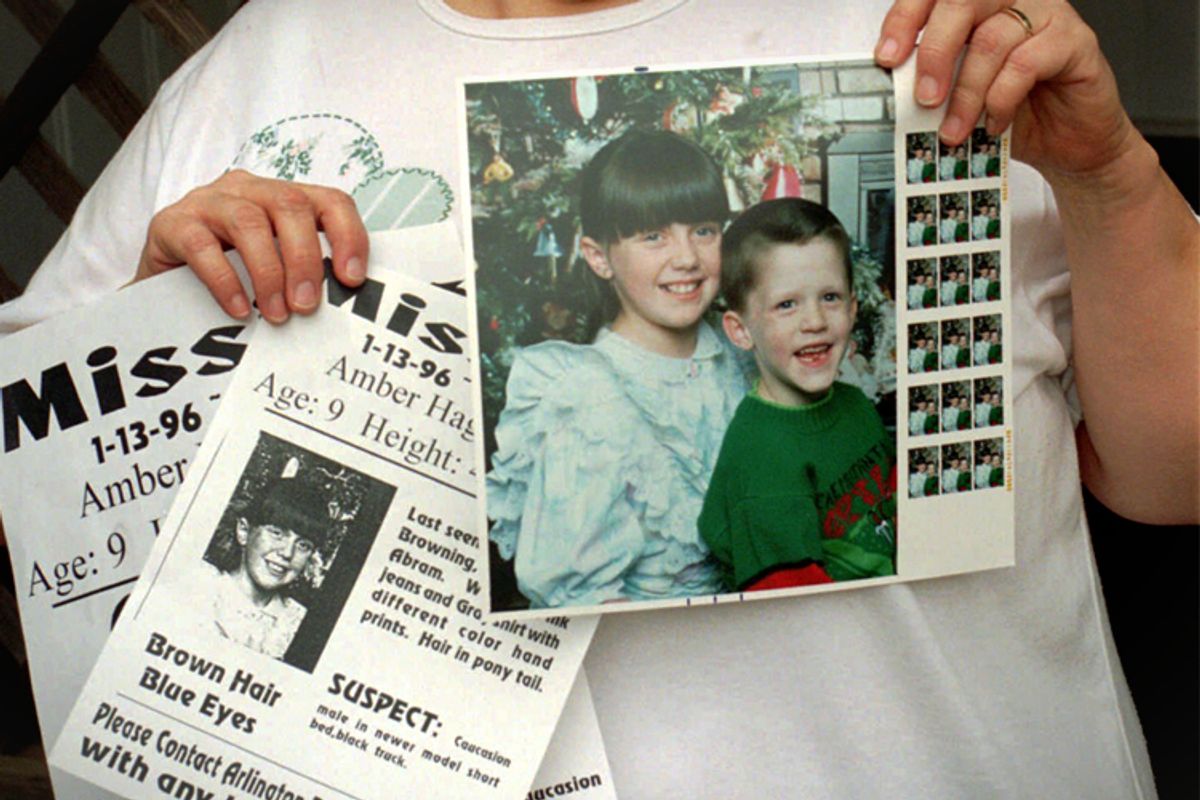

The AMBER alert is named in honor Amber Hagerman, who was kidnapped and killed in 1996, and whose murder has never been solved. Today, the AMBER alert bulletin system works across a variety of platforms to get the message out as widely as possible when a child or children are believed abducted. The Office of Justice claims that the "AMBER Alert programs have helped save the lives of 656 children nationwide."

Bringing as much attention to a possible kidnapping in progress and enlisting the general public appears in many regards a smart way to bring missing children home and bring criminals to justice. The man responsible for sending out Monday's alert, Bob Hover of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, told KABC Tuesday, "The more eyes and ears searching for a child in a critically dangerous situation are way better and far outweigh the eyes and ears of just a couple. We feel that it's an important system. It's going to save lives and protect property." That's the hope – and last month, an 8 year-old Cleveland boy was found after a local man recognized the suspect's vehicle.

But the reality is that at 11pm on a Monday California night, not everybody who has a phone is automatically involved in the "searching." As Joe Curren puts it, "What am I supposed to do from my couch, near midnight, at the other end of the state?" The reality is that, as an LA Times commenter said, there is not yet any way to filter the messages, which is why, after getting ten alerts in the span of ten hours, he opted out entirely. "I won't get ANY alerts that are sent out," he said. "I'm sure this isn't what you had hoped for." The reality is that even advocate Marc Klaas, the father of Polly Klaas, who was kidnapped and killed in 1993, has reservations. "It's an incredibly harsh sound," Klaas told the LA Times Wednesday. "And it provides you with almost no information. I think the intention is good, but the application itself is pretty awful."

The agonizing nightmare of a missing child naturally inspires all of us to want to pitch in to help, and the urgency of a potential life or death situation can sometimes depend on the public's help. And though KABC says that "many have complained about the inconvenience," that's not the issue. Most of us can handle an interruption. What's concerning instead is the way the current system has been implemented, how it raises serious questions about cellphone users' privacy. What's frustrating is that it's been rolled out in a way that's so loud and persistent it seems best designed to make people want to not participate. And more significantly, given how emotional the issue of child abduction is, it's distressing to consider what might happen when some self-styled heroes decide to spring into action based on a widely disseminated description of a car or a suspect. The assumption that "the more eyes and ears" is best is highly unscientific. It neglects the increased potential for false leads, misinformation, cruel hoaxes and vigilantism -- and the resources they can drain. And hey, not that crowdsourcing doesn't always go perfectly, but you know, sometimes, putting a small amount of information in the hands of many leads to some pretty dangerous and stupid mistakes. The last thing an awful situation needs is more awful added to it. And as of Wednesday afternoon, Hannah and Ethan Anderson are still missing.

Shares