Hannah arrived a few minutes after eight, apologizing for being late. "I have no excuse," she said, as she slid onto the bar stool. "I live just down the street."

Nate caught a whiff of coconut shampoo.

While she deliberated between a Chianti and a Malbec, with her head tilted away from his and her lips slightly puckered, he noticed that Hannah looked a lot like a girl he knew in high school.

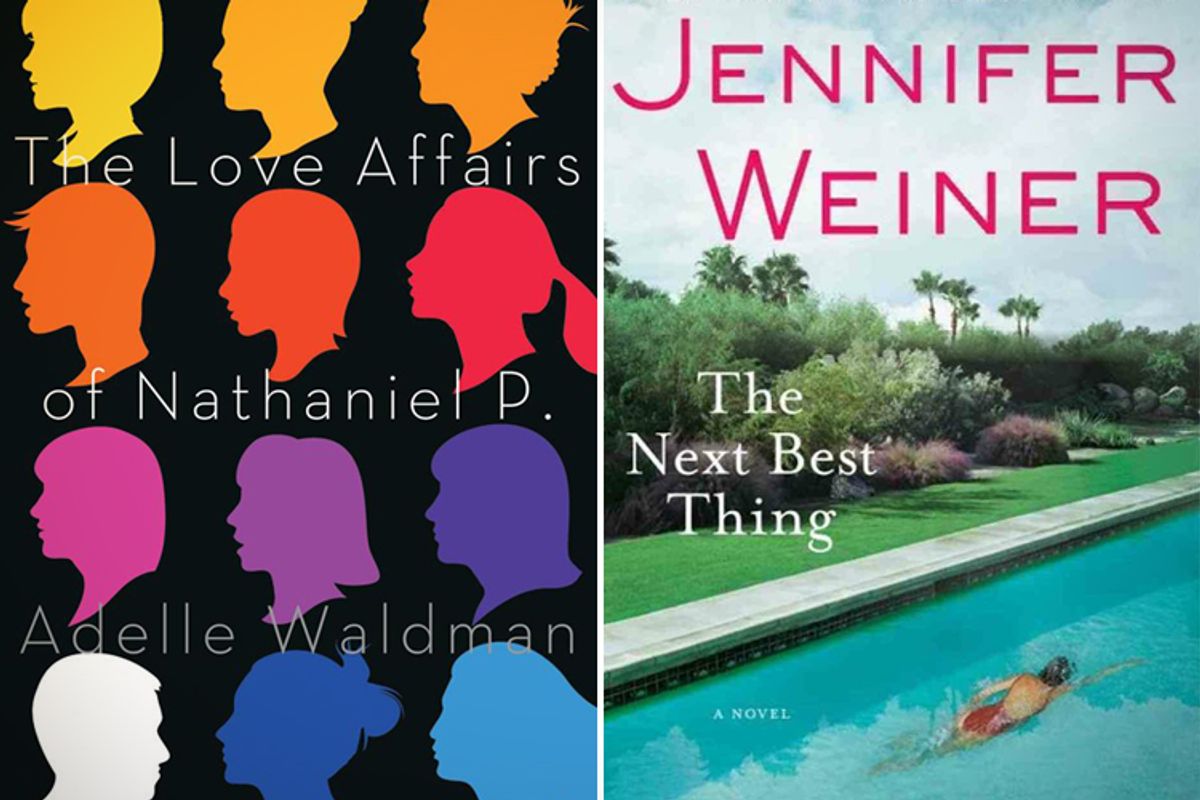

That's how the first date between Nate and Hannah begins in Adelle Waldman's "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.," one of the most buzzed-about debuts of the summer. "Waldman just may be this generation’s Jane Austen," raved the Boston Globe. "A smart, engaging 21st-century comedy of manners," praised the New York Times Book Review. The best debut of the summer, announced GQ, and Harper's, the Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times murmured their assent.

It's been a banner summer for the literary novel that assays relationships between men and women. Both Waldman's novel and Gabriel Roth's "The Unknowns," for example, detail the dating lives of young men in big cities whose hearts -- and other parts -- lead them off-course at times. Roth's reviews have been as glowing as Waldman's, including a much-desired rave on the cover of the New York Times arts section. His book, it was suggested in a Telegraph review, might make him the heir to another, elder Roth -- or, at least, a more charming and witty version.

So what makes these books -- both smart, witty novels, to be sure -- worthy of comparisons to Roth, Austen and Updike, while other books with similar boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl themes and similar settings (chic Manhattan book parties, San Francisco tech soirees) get dismissed as genre fiction or chick lit?

The chick-lit wars are hardly new. The best-selling authors of the commercially viable female-oriented genre, including Jennifer Weiner, have vociferously jumped into the fray to defend their work against authors who seem to (implicitly or explicitly) defame it at every turn. As Jodi Picoult told the New York Times Magazine this year: "Women are reviewed less frequently and differently than men and there are fewer female reviewers," adding that as a potential subject for the sort of reviews Waldman, Roth and others get, "A woman who writes genre commercial fiction would be great, even better if it’s a woman of color."

But the question remains this: Why are some books about relations between the sexes taken seriously and deemed worthy of review space in the New York Times and Washington Post, while others mining the same territory get derided or ignored? Is it as simple as a setting within the Brooklyn literary world? What makes one book literary fiction and another genre?

"To me, the novels I like and am counting in the serious fiction category would, I hope, try to be very honest about how people are," Adelle Waldman told Salon, "and less concerned with providing escapist pleasures and more concerned with providing the pleasures of incisive analysis -- and maybe humor."

She noted that she herself did not use "literary fiction" as a category ("I think of that as something publishers think about").

Waldman's self-analysis gets at the heart of a debate that has consumed literary circles this year -- one set off when Claire Messud, speaking about her book "The Woman Upstairs" with Publisher's Weekly, decried readers' and journalists' interest in "likable characters."

"I didn't want to write a book with a plucky heroine," said Waldman. "I think a lot of novels operate in a world with a hero or heroine who's in some ways an underdog and you're rooting for them. If it's a heroine getting rid of a bad boyfriend and finding meaningful work and self-esteem, that's fine, I think. But I wanted my book to operate differently. We'd all like to see ourselves as a hero or heroine of a romantic comedy, but I don't think that accurately gets at how life really is."

Gabriel Roth told Salon that his novel sets up expectations of a more conventional coming-of-age tale before a significant rupture at its midpoint. But that's not the only thing that sets it apart: "Some of the vocabulary is just not language you'd typically find in commercial fiction. I'm more interested in style than a typical commercial writer," he said. "Those are qualities -- I don't want to say I'm bragging about my high stylistic abilities, but it's a preoccupation of mine, and a preoccupation of the literary writer."

Though Greg Cowles, an assigning editor at the New York Times Book Review who writes the "Inside the List" column covering best-sellers, was dubious of the term "chick-lit" ("I think that's a publicist's catch-all"), he noted that the line between literary and commercial fiction was, in his view, not one solely made up by marketers.

"A commercial book is not nearly as interested in character development or quality of prose. The characters are implausible or predictably just fulfill a role in service of the story, they don't have surprising ideas or insight. They're much easier to read. They're commercial! And people are happy to confirm their prejudices or just read something for story."

As for why books like Waldman's get reviewed while commercial books are reviewed far less commonly, Cowles said, "Ideally, when we assign a book, we want the review to be able not only to summarize the story but analyze what's going on in the book. Frankly, a lot of lesser genre writing -- and lesser literary writing -- doesn't offer as much to discuss in terms of their ideas, their writing, their characterization."

Liesl Schillinger, a frequent contributor to the Book Review, added: "What is popular is not literary but it's not necessarily not valuable. With literary writing you just are aware of the author's gifts and ambitions, to a lesser or greater sense. It doesn't have to be very tricksy."

So literary fiction is literary because you know it when you see it. But do literary characters in works like Waldman's, standing in for very specific New York "types," really tell us more about the contemporary condition than did, say, the very best characters of Candace Bushnell? Is anything more surprising than the commercial novel that gets, swiftly and fluently, to the heart of the contemporary condition -- and finds itself bereft of reviews?

Little wonder that so much of the divide hinges upon intangibles, like the aesthetics of the book jacket. Waldman's book cover, showing several women in profile, was much-labored-over to send exactly the right note to potential readers -- say, men who wouldn't want to be caught on the subway reading a book with a stiletto on the cover. GQ would never call that the debut of the year!

Roth, meanwhile, worked closely with his publishers: "I was wary of presenting it as a straight-down-the-middle commercial book. It would be deceptive and readers would be annoyed. They'd be justified in feeling ripped off. So I want the packaging to present the thing that would find readers who would enjoy it." Work is put in to ensure not merely that the novel finds its ideal reader -- or reviewer -- but to avoid finding one who would resent the nearly $30 they paid for something dark.

"I don't think my book is for everyone -- that's OK," said Waldman. "I'm OK with a live-and-let-live thing. I'm a big fan of [Jonathan] Franzen. Some people don't like his characters or his books. That astounds me as a reader, because I do. To my mind, it would be better if those people put down Franzen and that we on the other side do the same. It could be mutual non-hostility, or non-condescension."

Weiner, the prolific novelist (most recently of "The Next Best Thing") and an outspoken critic of the media's treatment of "chick-lit," told Salon that an aggressive sort of differentiation is at work: "It's a force of tension for a lot of people: Do you want readers or do you want reviews?"

"A book club will by all means pick up Franzen," said Weiner. "It's being written about everywhere -- you can't avoid it. But are they going to read 'The Unknowns' or even [Meg Wolitzer's] 'The Interestings' -- books with covers that are not playing into warm and fuzzy feelings or with a portrait of a woman shot from the back, the kind that say to book clubs, 'This one's for you'?"

Likely not in hardback -- but Weiner noted that, much like Jeffrey Eugenides' "The Marriage Plot," whose cover image went from Art Deco ring to, yes, woman shot from behind in its successive hardcover and paperback editions, the publishers of this season's books that ride the line between commercial and highbrow would likely be compelled to change their covers upon paperback release. "Hardcover is when you get the reviews and the profiles," she said. "Paperback is when you get the readers."

Weiner was surprised -- on behalf of Waldman's publisher -- by the "Nathaniel P." author's remark about not wanting the sort of readers who want likable characters. "I can't imagine someone's publisher jumping for joy," she said. "You should be saying 'You'll laugh! You'll cry! You'll remember being single!'" However, she said, writing as a woman was a minefield for anyone who doesn't want to be seen as a chick-lit queen. "For women who want to be perceived as literary writers, you've got to be extra distant, to prove you're not doing this degraded, dismissed thing. Writing in a guy's voice -- ain't nobody gonna think it's [chick lit] if it's in a male voice. And then the cover!"

The difference in marketing, Weiner said, is purposeful, designed to pitch the writers as serious: "If you're writing a novel about going to bars and parties and what wine you're bringing -- if you don't want that read by the people who'd pick up a Lauren Weisberger novel, you'd better take every step you can, from the cover to the narrator's voice to the ending to how you sound in interviews -- even how you look in the author photo. Don't smile!"

But even conceding that Waldman's and Roth's books are stylistically and substantively different from Weiner's doesn't change the fact that the perception of the books as graver and more serious is at least somewhat the result of sheer force of will and marketing.

Waldman said as much -- that dating is not generally, outside of the reception for her own book, treated as a serious subject. "They're first-world problems to a degree, but they're real problems, figuring out how it can work. It can be emotionally brutal. I sort of think it's a shame that we, as a culture, treat things that deal with dating as solely fit for romantic comedies -- which are great and I enjoy them. But in books, it's not treated as a serious subject. And it's inherently no less serious than books about war and politics."

Shares