I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them,

And the white skeletons of young men, I saw them,

I saw the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war,

But I saw they were not as was thought…

– Walt Whitman, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”

A MAN WITH a scythe cuts into a sea of wheat. His back to us, he is everyman, any man, and war is not apparent. Not until you read the title, “Veteran in the New Field.” Looking at the painting, its wheat stalks hemming him in, I get a profound sense of loss. These are no amber waves of grain, this not the stuff of anthems and glory, not hope or national pride. Instead it’s returning from war and being lost, a theme still trenchant today.

Winslow Homer, The Veteran in a New Field, 1865. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Winslow Homer painted it with an antique scythe, no longer in use, for its Grim-Reaper associations. Add to that other historical details like how in the Civil War crops were destroyed in battles staged across field and farm. Or that after the war the harvest was so great it seemed like providence – or vindication – to those in the North, and the painting’s meaning increases. On an even closer read, you could assume the veteran himself might be Homer. He served, embedded we’d call it today, as an illustrator for Harper’s, and in the painting’s foreground are his regimental jacket and canteen. By accident of his name, looking at the composition I compare it to another Homer, to The Odyssey, and the struggle to return home after war with the metaphoric seas to cross to reach a patient, faithful wife. The Veteran alone makes the Met’s pair of twinned shows commemorating the sesquicentennial of Gettysburg worth seeing. In fact, Homer manages to capture the Civil War’s impact, the perpetual afterwards which seems to continue today in this, our year of anniversaries, with Gettysburg and the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, 50 years since George Wallace’s inaugural address promised, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” and 50 since the KKK firebombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four girls, to this our own year of Travyon Martin and the Supreme Court’s gutting the Voting Rights Act. In other paintings in the show, Homer exposes the dis-ease that resulted after the war in moving works capturing African Americans – Americans finally – in an anxious relationship with their country and future as if he could see straight into the present moment.

In the Met’s other anniversary show, “Photography and the American Civil War,” one gallery is full of photos of men, none of whom smiles. To smile is impossible; the exposure takes too long to hold a grin, and the men are solemn with purpose. They stand and stare at the camera, at the viewer, at us. Some still have names; some pose with brothers. Others hold prop pistols and sabers. Some men shell out to have color added to their reproductions in what looks now like an eerie theatricality, rouged cheeks meant to add life and verisimilitude. All hold themselves stiff against death like the earliest portraits painted in New England. These are created as talismans and markers, the “I was here” in case death comes. One man who died anonymously – this the era before dog tags – was identified by a photo of his three children he carried with him. Discovering his name became a cause célèbre. The photograph was republished in newspapers across the country in hopes that someone would recognize the children and attach a name to the soldier, as if in finding that one man’s name, a larger wrong might be righted. Here, the photos of anonymous, lost men are dulling simply by the weight of sheer numbers, and this only a small fraction of such photos created. They pale, however, in the face of statistics from the war: two percent of the nation’s population died and one fifth of all combatants.

Other images show pastures of death with bloated bodies, and the starkest image of all is John Reekie’s, A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia. In a field in black and white, four African-American men, freed slaves working for the Union, collect bleached white skulls. The image has an awfulness you won’t see now.

John Reekie, “A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia,” April 1865. From Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War (1866), vol. 2, pl. 94 Albumen silver print from glass negative. Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library.

This was the first war with extensive photography, and it changed how we saw that war and war in general. Because the equipment was clumsy and heavy – glass plates, cameras as giant contraptions, not to mention exposure times of two minutes or more – the resulting pictures were never of the action, not the moment of glory and the valor of battle but its aftermath. Empty fields, bodies, scarred land – loss. With this, the art of war went from the stuff of history painting, from myth and heroism, to something more meditative. And, because what was left to shoot was often empty fields and barren ground, nature here was freighted with significance. This use of it (a kind of capital-N Nature) was in keeping with contemporary views growing from the romantic Hudson River School and Bierstadts’s overwrought paintings of Yosemite.

But in the photographs, the images of war are far more graphic than anything you will encouter today. It’s as if Hector’s body were dragged through the streets in The Iliad, so shocking to see you’d assume the pictures break a convention – if not the actual Geneva Conventions—about what we can show. They don’t. Because we get such sanitized shots of combat now, I’d assumed the Geneva Conventions (penned though it was for later wars) forbids photographing the dead. It does not. A friend in the Army said the only thing violated here is our stomach for the consequences of these actions. “The press has not been fond of showing the reality of the current wars. That has more to do with advertising revenue than any legal prohibition. It’s a strange world,” he says, “where people can seek out the most obscene images on the web at will but the network news will self-censor anything not fit for a third grade classroom.”

~

Despite the power of some of the images, the shows are uneven. Both overreach, one in how it’s hung, the other in its ham-handed wall text. The photography exhibition has a silly, Disney-like hanging, using heavy tent canvas as if to create the illusion of gee-we’re-in-a-Civil-War-tent. There’s also moody lighting and blood-red walls. In theNew Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl wrote all that is missing is “Ashokan Fairwell.”

That red room, the penultimate gallery, is full of medical photos of veterans. Meant as documents of surgery and treatments, the hollow eyes and wounds haunted me. And the show was so dense, by the end I stumbled out dizzy and dazed, unable to string a sentence together as if the show created the sensation of living through a war. I’m not sure that was the intended effect, but the result is almost laudable.

“The Civil War and American Art” too is flawed. Take the text accompanying Winslow Homer’s Veteran who “cannot retreat, for the cut stalks behind him block his backward step. Wheat fills his field of vision, just like the memories of battle that fill his head.” To which I am left thinking, really? And you know that how? His moving The Cotton Pickers is annotated: “Is there any hope in the future for these two free field workers? The woman at left looks down, focused on her task. Cotton surrounds her, as though her world is circumscribed by her work in the fields. Her companion, head up and eyes alert, gazes with determination at what lies beyond. Her sack holds the cotton she has harvested but might easily serve as a sack for her belongings should she dare to step forward into a different life.”

Winslow Homer, “The Cotton Pickers,” 1876, oil on canvas. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Digital Image © 2012 Museum Associates/LACMA

Take Homer away from the show and most of what is left is genre painting, hokey at best with a Saturday-Evening-Post saccharine quality like Jervis McEntee’s The Fire of Leaves. In it two kids, one in Confederate dress, the other Union blues, burn autumn foliage. The idea being here that war doesn’t matter to children, or they can transcend it. Or take the painting of a Maine sap house and its workers, which records an interesting fact that abolitionists used maple sugar as a sweetener instead of refined sugar that came from plantations. What stands out are works like Sanford Robinson Gifford’s Fort Federal Hill at Sunset, Baltimore with its solitary soldier and Rothko reds – and the work of Homer. Over and over Winslow Homer, painting war, fighting men or a lone soldier staring at a grave. That composition is all elongated lines, and the trooper’s anonymous face stares down. You don’t even see his eyes. Also powerful are Homer’s African-Americans, like his “Cotton Pickers” or “A Visit from the Old Mistress,” where a white woman comes to implore something from three black women. In these he hints at what’s to come – confrontations and difficulties. With their guarded expressions, his women are more eloquent than words.

The uneven quality of the work in “The Civil War and American Art” leaves me with a question: what is the role of art and war or war-art? Seeing the sugar house and burning leaves, which veer on kitsch and propaganda, I wonder what we’re supposed to find in them now 150 years on? Are they documents? Art? A way to understand that cultural moment? And, what is it we now expect of art and war? Do we want Walt Whitman or a witness? Or something more?

This question makes me think of another veteran, Vietnam vet Kim Jones and his performances as Mudman. As if channeling his alien presence in the world to which he’d returned after serving, he started appearing on streets and galleries in Los Angeles wearing combat boots and caked in mud with sticks elaborately strapped to himself like some metaphoric backpack a grunt carried. He also makes mural-sized drawings of abstract battlefields populated by endless Xs and Os as if diagrams of battles being fought in his mind.

Threaded through these is his biography, and his work is powerful because it doesn’t record a simple fact but something more unsettling, more like the experiences of Homer’s Veteran, and this seems to be what we need of our artists and war now. In the novel The Yellow Birds Kevin Powers writes, “All pain is the same. Only the details are different,” and indeed that book about a private and his sense of failing against expectations seems to be for those who didn’t serve. Its larger theme is the unspeakable nature of war and how that seeps into a soldier’s return. And, it brings me back to Whitman. While “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” is a lament for Lincoln, those lines about soldiers and death, about they’re not being “as was thought,” continues by talking about the ones who lived, the ones who survived. That seems to be the point of war-art. These works exist for those who did not go, who stayed behind, weaving and unweaving like Penelope. Whitman writes –

They themselves were fully at rest, they suffer’d not,

The living remain’d and suffer’d, the mother suffer’d,

And the wife and the child and the musing comrade suffer’d,

And the armies that remain’d suffer’d.

This is the power of Winslow Homer, Kim Jones and Kevin Powers. It’s about articulating the unspeakable. My friend, the one I asked about the Geneva Conventions, has said, “I think fiction – more than history – helps people understand. But I don’t need fiction to understand a soldier’s life in Iraq. Frankly, it’s all still way too close.” Reading those works is for those who didn’t serve, who don’t know.

It’s impossible to divorce my take on Winslow Homer and war and art from the decade plus of our current wars. Add to that a lingering national guilt over Vietnam and its veterans, who returned and suffered like Jones’ Mudman as if landed in the middle of a foreign world, their burden stuck to their back. He’s described that time, saying, “I was an outsider, a spiky thing, walking through the main artery of the city. Molecules fit in, but if something’s spiky it doesn’t fit in.”

I think here too of how popular war writing is now with Powers and Phil Klay’s upcoming novel or Anthony Swofford. It reminds me of how contemporary art has often asked people (women, blacks, gays and lesbians…) to make work about their otherness. Part of this comes from art and literature’s liberal stance and wanting to understand, and we do need to, but it makes me think of my friend. I keep encouraging him to write about his experiences. He’s had three tours of Afghanistan. On the last all he took to read was Shakespeare. If he doesn’t have something true to say about war, who does? He doesn’t want to write that, though I want him to.

Such demands also remind me of what a friend teaching in a prestigious MFA program said about one of the students there, a young veteran. Everyone seemed to plea with him to do something with his experiences, telling him he had insight no one else did. “Faculty members kept saying,” my friend relates, “he had ‘such a unique experience for an artist.’” She found it all patronizing. It was and is, but we also need to understand. When the New York Times reviewed The Yellow Birds last year, the suicide rate among veterans and active duty military was eighteen a day. Now it’s 22. That is nearly one person who has served our country, us, dying an hour.

There’s a line on a Sojourner Truth photo in the Met’s photography show: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” She wrote that caption herself. She staged the image of herself. She was willing to sell it (and by inference a bit of her soul as the text suggests) because she knew what she would gain, what people would gain from it. So, she posed herself knitting, she a feminist, an abolitionist, a Methodist minister, there doing traditional women’s work. She was going to choose how she used herself, her body, her image. “I sell the shadow….”

We need veterans to tell their stories, both as documents and art. As my friend who served said, fiction is better to help us understand. And, we do need to understand. Veterans are always woefully under-appreciated after the Civil War and after our current wars.

~

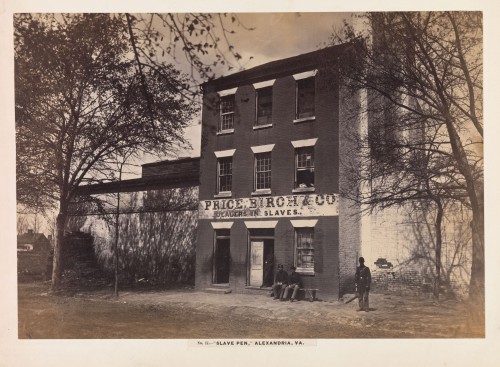

I love art for the multiple meanings it can express, but there is still the power of the document, of a record. Such is the photograph of the slave pen in Alexandria, Va, something that looks banal, like an old warehouse. I grew up in Alexandria, drove by the building often on my way to high school. I had no clue about its former use or that the firm had been the largest slave traders in the antebellum South. Virginia is the South, but I was from “Northern Virginia,” emphasis on the northern.

Andrew Joseph Russell (American, 1830–1902) “Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia,” 1863. Albumen silver print from glass negative. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

I look at the photo of slave pen now and think of a bronze statue Appomattox three blocks away. The monument is of a Confederate soldier, facing south, staring at the ground, bereaved upon the Lee’s surrender. The day the sculpture was dedicated in 1889, thousands turned out to celebrate, including Joseph E. Johnston, former Confederate general. When I was little, we’d pass it often taking my dad to the airport for his business trips, and somehow I conflated the two. I thought the statue was my father. I was four. What a Jewish man from rural Pennsylvania who’d had a cross burned on his lawn as a kid could have to do with a defeated soldier fighting for slavery, I have no clue. On the other side of that question is my maternal grandfather’s family. They fought for the South. Someone beat a slave to death. You can read online about Elizabeth Jackson there on Versailles Knoll reciting the psalms praying for forbearance as her sons served.

It would be impossible to express in words the horror of this unfortunate conflict. With three sons actively engaged in combat, unrest among the slaves and war-time shortages in all supplies, Francis and Elizabeth tried to cling to their beautiful faith and carry on as best they could. Elizabeth followed a regular morning ritual. When first arising, she would stand on her open south threshold, gaze at the majestic Versailles Knoll and quote: ‘This is the day that the Lord hath made; we will rejoice and be glad in it.’ (Psalm 118:24). ‘I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.’ (Psalm 121:1). This threshold is considered a sacred spot by the descendants of Francis and Elizabeth.

I don’t know how to adjust to the calculus of that. My ex-brother-in-law, the person who took me to my first punk shows, is a Civil War re-enactor. On the Confederate side. He insists when we speak about it, that the war was not about slavery. The statue,Appomattox, got knocked over not long ago when it was hit by a car. It was put up again. It’s protected by state law (a law passed the year the statue was unveiled). What I don’t understand is why it doesn’t get overturned today.

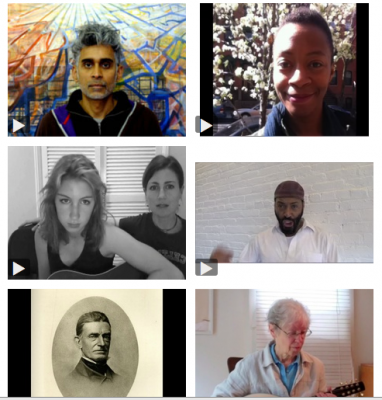

Laylah Ali, an artist in Massachusetts, did a video piece recently asking people to film themselves singing “John Brown’s Body,” aka “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Here, the stirring lyrics are earnest, patriotic and humble. Taken as a whole, the lone voices singing – black and white, young and old – add up to something particularly moving. Done for the anniversary of Gettysburg, the video project went up on Dia’s website just before the Fourth of July.

Talking to Ali about the project, she says, “The Civil War still has a palpable presence, if you are paying attention. The project is partially meant to speak obliquely to the progress that has come since then —and also at the same time, the exact opposite. The Civil War is still being fought in this country, and you can see that with recent Supreme Court decisions about voting rights, the entrenched resistance and refusal to accept Obama’s presidency, the incarceration rate of black men in the US, etc. etc.” (That very “etc, etc” feels laced with 150 years of etceteras and post-Civil War rancor and racism). “There has been,” she says, “a great deal of revisionist effort expended on making the Civil War one where each side had a kind of integrity and did what they thought was right. At the Harper’s Ferry historical site, the park rangers have to portray John Brown in a ‘balanced’ way that won’t offend the Confederate sympathizers who come through. Overall, Robert E. Lee is given more respect than John Brown. (Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis both had their full citizenship rights restored, Lee by Gerald Ford and Jefferson Davis by Jimmy Carter—and neither Lee nor Davis were executed for being traitors.)”

Meanwhile the movie Lincoln, celebrating the heroic efforts to eradicate slavery, changed the names of the Senators who voted against the Amendment, so as not to embarrass their relatives today. And, when it comes to talking about the Thirteenth Amendment, my ex-brother-in-law points out that it passed at the end of the war, not the beginning, as if to prove his point about slavery.

Such revisionist histories are a shame, of which we should be ashamed. I see the slave pen in the town where I grew up, and I am ashamed. I read about my relatives there in Versailles, Tennessee, and I am shocked. We all need to be shocked still, and it’s hard to be. The Civil War is written about and celebrated so often (particularly when anniversaries turn up) there is hardly anything that can give weight to its vastness. It’s a subject so big it still seems to suck the air from a room. Indeed, as the people sing in Ali’s videos: John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave and his soul goes marching on…

Shares