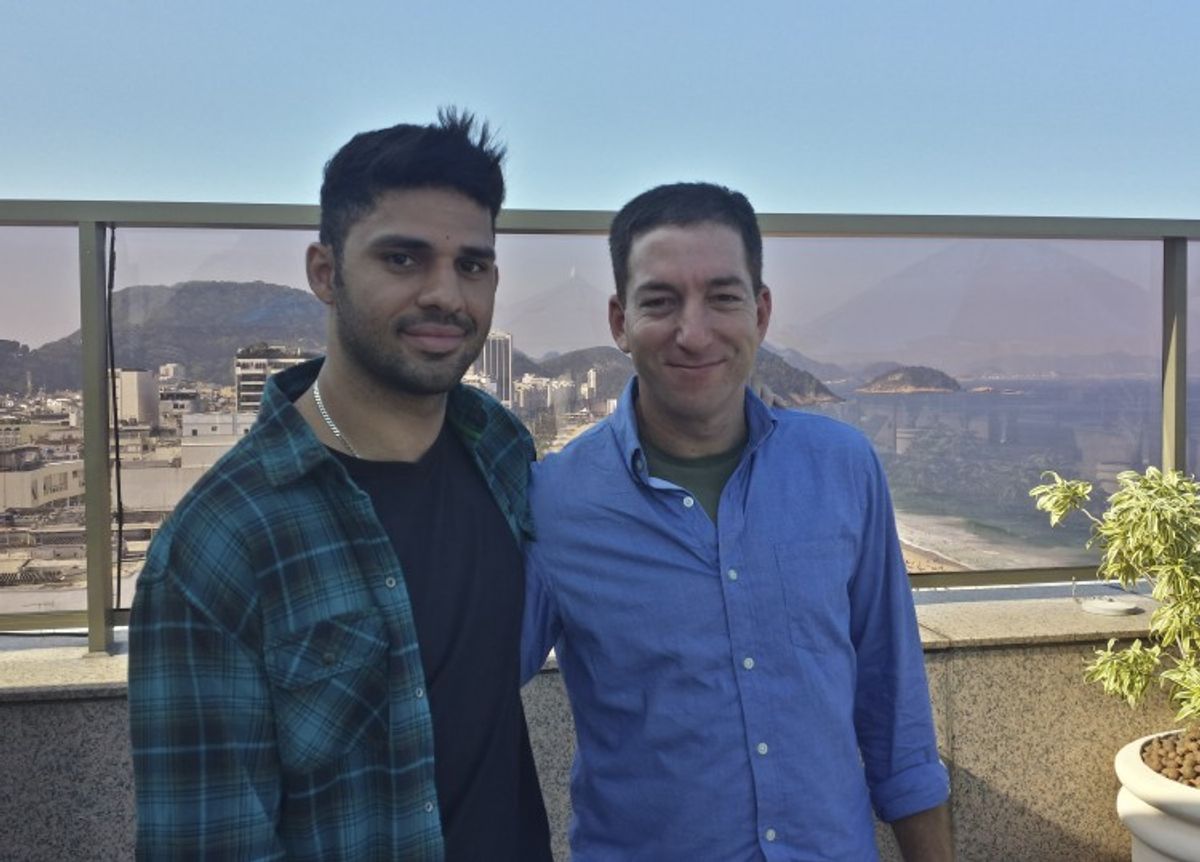

As has been reported, Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald’s partner, David Miranda, was detained at Heathrow airport this weekend, in London under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000. Greenwald, famous for exposing the National Security Agency’s mass surveillance project, described the treatment to Miranda as both "despotic" and an attack against journalism. “It's bad enough to prosecute and imprison sources," he stated. "It’s worse still to imprison journalists who report the truth.”

Unwarranted detention is something ethnic minority communities and, in particular, Muslim communities have also experienced with Schedule 7. For example, statistics show that between April 2011 and March 2012 almost 70,000 people were questioned by officers at British ports and airports and 45 percent of these detainees were of Asian or Asian British origin.

A visibly shaken Miranda recounted, “I remained in a room, there were six different agents coming and going, talking to me … They asked questions about my entire life, about everything.” The case has caused anger and outrage in the U.K., as the chairman of the Home Affairs Select Committee, Keith Vaz, and shadow home secretary, Yvette Cooper, said the police needed to explain why they used terrorism powers in this case. Indeed, the independent reviewer of counterterrorism legislation, David Anderson, has asked the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police to explain why anti-terrorism laws were used.

Schedule 7 gives the police the power to stop and detain an individual and search passengers both at ports and airports to try to determine whether they are terrorists or not. They can also be detained, as in Miranda’s case, for up to nine hours and their possessions can be examined. The problem, however, with this statute is that it assumes someone is guilty of being a terrorist without actual evidence of criminality in the first instance.

This is why Greenwald, himself, described the incident as a means to "intimidate" and "bully" him because of his writings and revelations regarding the NSA. Greenwald stated, “They never asked him about a single question at all about terrorism or anything relating to a terrorist organisation … They spent the entire day asking about the reporting I was doing and other Guardian journalists were doing on the NSA stories.”

If that is proven true, and I tend to agree with him, then this would be deeply damaging for both the U.K. government and the British police. Indeed, apart from the clear links between this incident and Greenwald’s revelations of the NSA story, the impact of this incident upon innocent people such as Miranda should not be underestimated. In his case, like many others, there is a deprivation of both liberty and an intrusion of his privacy.

A case brought before the European Court of Human Rights, by Sabure Malik, a British national, also shows that Schedule 7 can have a long-lasting effect on someone. After being detained under Schedule 7 following a trip to Hajj, he was marched through the terminal by police officers and bundled in the back of a police van. Malik would later describe the incident as a humiliating experience and, like Miranda, he had his possessions examined. In his case, the detective inspector noted that an officer under Schedule 7 “does not require any reasonable grounds to stop a person and conduct any such examination.”

It’s because of this intrusion of privacy and an absence of reasonable suspicion that a consultation took place between September and December of 2012 to examine the implications of Schedule 7. It found that many respondents were concerned with the disproportionate use of it against ethnic minority communities. For example, questions such as "which Mosque do you attend?" or "how often do you pray?" were viewed as negative and Islamophobic.

The Terrorism Act of 2000 was enacted in order to combat the international threat. However, this case has again highlighted the problem with such laws when exercised for spurious reasons. The Terrorism Act allows the police to act in this way because in many cases they do not need evidence to justify detaining someone. As long as the court has evidence that they are carrying out their investigations diligently and expeditiously, this will suffice.

This undermines these due process rights, undercutting the right to liberty, the right to silence, the right to be promptly informed of any charges and the right to be free from detention. It can also pave the way to abusive practices, which might result in detainees making involuntary statements and confessions. Further, it is an unnecessary curtailment of a suspect’s freedom for the sake of prolonged and speculative investigations by the police.

In this case, it was a heavy-handed decision to hold someone who clearly was not a terrorist or a threat to British national security, but merely for his association with Greenwald, Miranda had to suffer at the hands of the U.K. authorities. Surely, now, people must recognize that the golden thread that runs back to the Magna Carta of justice, due process, and the principle of habeas corpus are being undermined by anti-terrorism laws that target innocent people like Miranda.

Shares