If you thought the War on Women ended in détente on Election Day in 2012, or that Republicans fought it to a draw earlier this year by obscuring weaknesses in their policy platform with San Diego Mayor Bob Filner's bad behavior, think again. We already know that immigration reform and voting rights -- issues of top concern for two key Democratic constituencies -- are likely to be central to next year's midterm campaign. Women's equality will round out the trifecta.

New polling data from the Feldman Group and Anzalone Liszt Grove research finds that women cite lack of equal pay as their single biggest workplace concern and that for a majority of them, it's a high-intensity problem.

The data, culled from a three-day survey of 1,000 women who participated in the 2012 election, was compiled for a new group called American Women, the 501(c)(4) arm of the group Emily's List, which will seek to increase public awareness of issues affecting women.

"Lilly Ledbetter was important but equal pay is still the number one workplace issue for women," according to the Feldman/Anzalone polling memo. "Seventy (70) percent of women say being paid less than men for the same work is a problem, including 51 percent who say it is a major problem."

The data finds that equal pay is an unusually large problem in cities, and among African-Americans, low-income earners, single women and women without college degrees. A majority of women in both the South and the West -- two regions in which Democrats hope to increase their representation -- cite unequal pay as a significant problem.

The missing piece here is legislative valence. If immigration reform was the 113th Congress' main charge, and the Supreme Court unexpectedly threw voting rights into Congress' lap earlier this year, where's the policy priority that will foist equal pay into the public consciousness and (most likely) help Democrats draw a sharp distinction between the parties before 2014? After all, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act has been law for more than four years now. So what else is there?

That's where the Paycheck Fairness Act comes into play.

Ledbetter makes it easier for women suffering discrimination to sue their employers. The Paycheck Fairness Act would make it harder for employers to pay unequally for similar work to begin with. But Republicans have filibustered that bill twice in the past two Congresses. Once in 2010 and again in 2012.

It's not dead yet, though. The Paycheck Fairness Act badly wrong-footed Mitt Romney's campaign when it came up for a vote in the Senate in June of last year. And Democrats believe Republicans will once again step on their own outreach efforts if and when Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid moves the legislation again in the coming months.

If Republicans in Congress assure that bills addressing none of these issues -- immigration, voting rights or equal pay -- become law before November 2014, it will give the three key demographics that have handed Dems the presidency twice in a row, but that aren't reliable voters in off-years, unique reasons to show up at the polls.

An important caveat here: Political science says elections don't usually work this way. Fundamentals matter more than discrete policy issues. But the GOP has already spooked itself with its inability to provide any of these constituencies evidence that they've awaken to their concerns. And we see more evidence of it every time a Republican candidate muddies his true record on reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act.

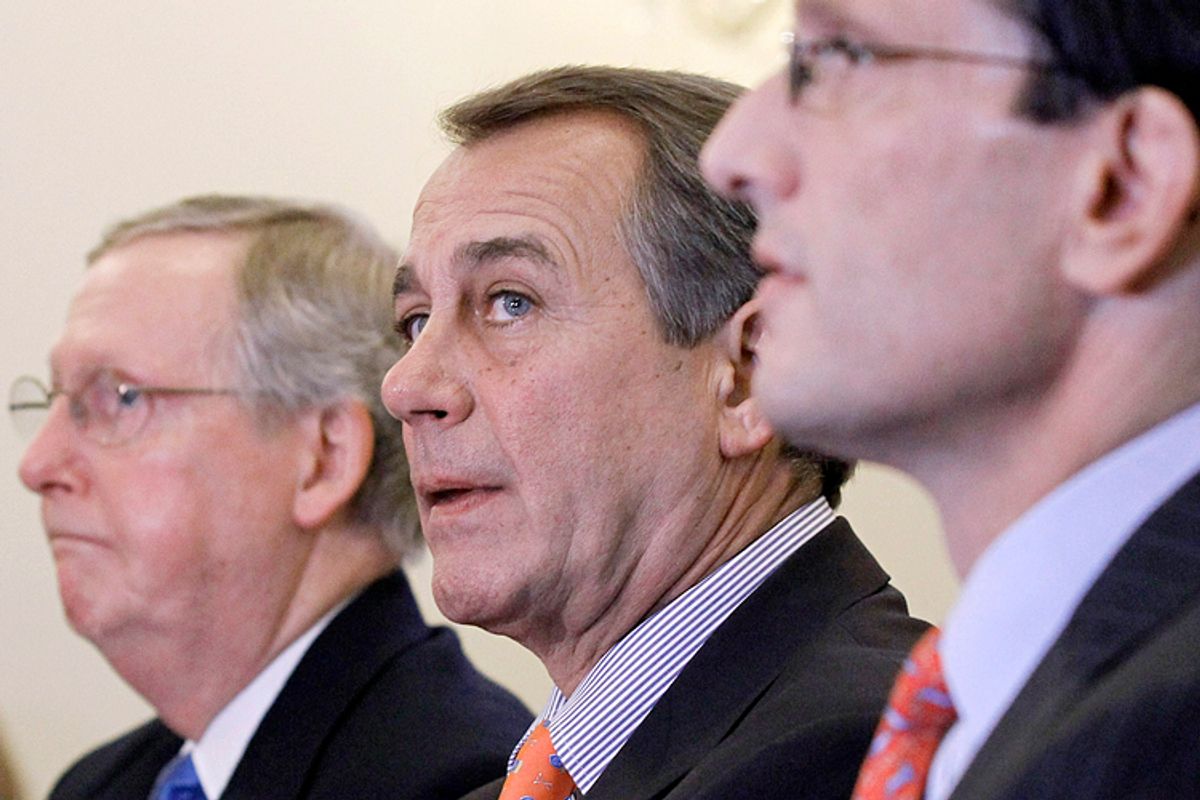

Most recently, Mitch McConnell's campaign distributed a press packet to reporters touting the Senate minority leader as a "co-sponsor of the original Violence Against Women Act [who] continues to advocate for stronger policies to protect women."

Here's the whole story, from TPM's Sahil Kapur:

McConnell did cosponsor a version of the Violence Against Woman Act in 1991, which never received a Senate vote. But by the time the measure came up again in 1993, McConnell was no longer a cosponsor, and in fact voted against final passage of the bill. In 2005, it was renewed by an unrecorded voice vote. In 2012, McConnell voted against the Senate-passed VAWA, which died in the House. Then early in 2013, he again voted against VAWA re-authorization, which passed the Senate by a vote of 78-22, and eventually passed the House and was signed into law.

McConnell is currently fending off a well-financed primary opponent in Kentucky, and if he succeeds, he'll be well positioned to win reelection in a state as conservative as Kentucky, notwithstanding his record on women's issues. But he clearly recognizes that his female general election opponent Alison Lundergan Grimes won't give him a pass on VAWA -- and he can safely bet the same is true of equal pay.

Shares