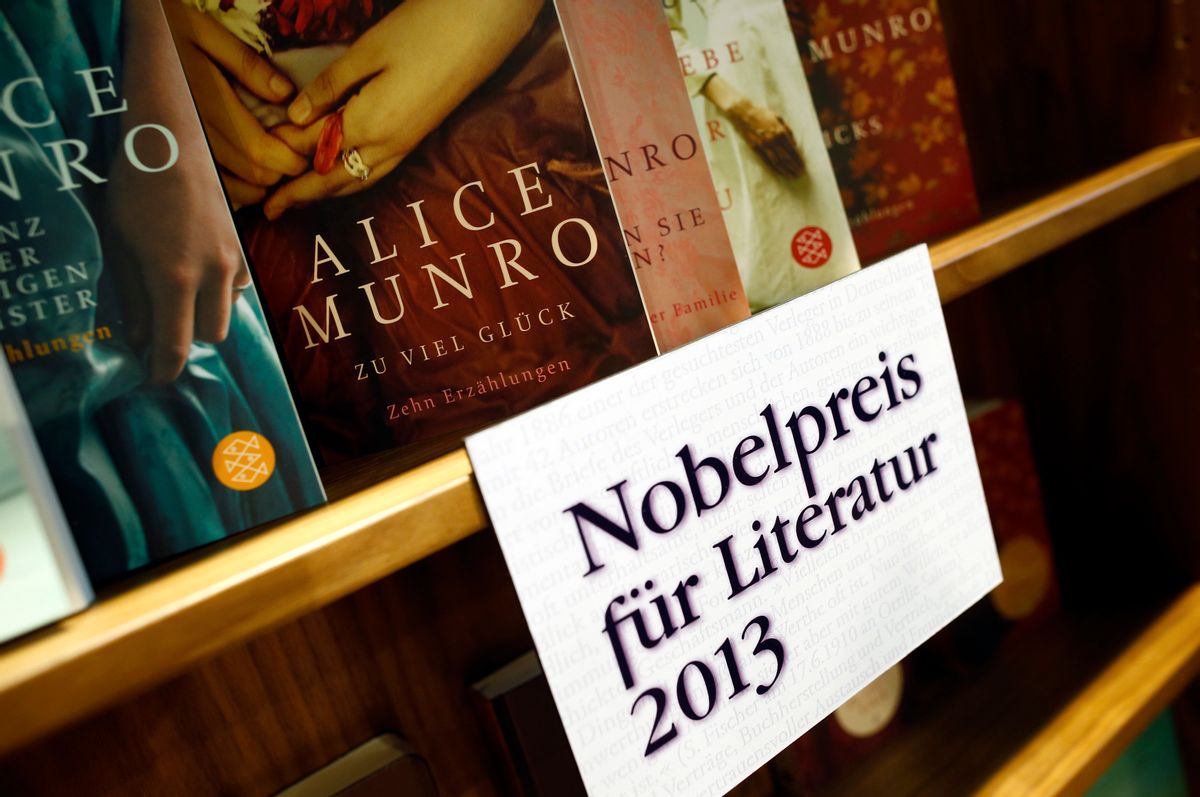

Alice Munro has won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature. The short-story writer is the first-ever Canadian, and 13th woman, to win the prize, and a rare laureate not to work in the novel.

Here are a few things to know about Munro's long career:

She's retired: Coincidentally (or, more likely, not), Munro's Nobel came the same year that she announced she had stopped writing. She had remarked in 2006, "I don't know if I have the energy to do this anymore," though she went on to have published "Too Much Happiness" in 2009 and "Dear Life," her 14th collection, in 2012.

She married young: In an interview with the Paris Review, Munro described the effect that having been married at 20 and having a child at 21 had on her work habits:

I was writing desperately all the time I was pregnant because I thought I would never be able to write afterwards. Each pregnancy spurred me to get something big done before the baby was born. Actually I didn’t get anything big done. [...] The year I wrote my second book, Lives of Girls and Women, I was enormously productive. I had four kids because one of the girls’ friends was living with us, and I worked in the store two days a week. I used to work until maybe one o’clock in the morning and then get up at six. And I remember thinking, You know, maybe I’ll die, this is terrible, I’ll have a heart attack. I was only about thirty-nine or so, but I was thinking this; then I thought, Well even if I do, I’ve got that many pages written now. They can see how it’s going to come out. It was a kind of desperate, desperate race. I don’t have that kind of energy now.

Her first collection was published when she was 37; a local paper ran the headline "Local Housewife Finds Time to Write Short Stories."

One of her signatures is altering chronology: In a review of "Dear Life," her one-time editor at the New Yorker Charles McGrath remarked that Munro had kept up a career-long interest in screwy timelines:

Many of these stories are told in Munro’s now familiar and much remarked on style, in which chronology is upended and the narrative is apt to begin at the end and end in the middle. She has said that she personally prefers to read stories that way, dipping in at random instead of following along sequentially, and this structure also echoes her view of the world, in which events seldom follow a plotline but merely happen, suddenly and inexplicably.

Her books share other similarities -- for instance, they tend to focus on small-town life in Ontario, and to deal with slow awakenings or realizations over time.

... But not everyone is a fan.

This year, Munro was at the center of a mini-firestorm when Christian Lorentzen systematically dismantled her work in the London Review of Books, writing against "the way her critics begin by asserting her goodness, her greatness, her majorness or her bestness, and then quickly adopt a defensive tone." He noted that the common themes in Munro's work seemed to him reworkings of the collection "The Beggar Maid":

... later versions of the first sexual encounter story (Rose is molested by a minister on a train; she’s disgusted but also likes it, ‘victim and accomplice’), or the adultery story, or the stale marriage story, or the lonely single mother story, don’t so much enhance the originals as point up their flaws, making them seem even more schematic.

On a less theoretical and more practical note, she had adversaries in Canadian public education, too: Munro complained after her work was banned by schools, referring in this interview to "pressure groups" unfamiliar with literature as banning books for political reasons.

She's prolific: Here, for instance, is the archive of her stories for the New Yorker, dating back to 1977. Once she got started writing for that magazine -- after years of rejection, beginning in the 1950s -- it was hard to slow down; she published three New Yorker stories in 1980 alone.

Not all of her short story collections are disparate stories: "The Beggar Maid" (that book the London Review of Books' Lorentzen said Munro had spent her career reworking) assays the life of Rose over the course of his life. The Millions called it "the Munro book to read if you’re only willing to read one but don’t like the idea of reading a literary greatest hits album [her 'Selected Stories']."

Jonathan Franzen loves her! This is rare. He called her "Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage" (adapted into a forthcoming Kristen Wiig movie): "Munro at her best, tirelessly observant, serenely free of illusion, deeply and gloriously humane.

Books are the family business: The bookstore she opened in 1963 with her then-husband, Munro's Books, is still in business in the Canadian city of Victoria. And her daughter Sheila has written a memoir about life with Munro, one that depicts being "used by the voracious and amoral writer who exists in the same person as her mother."

Shares