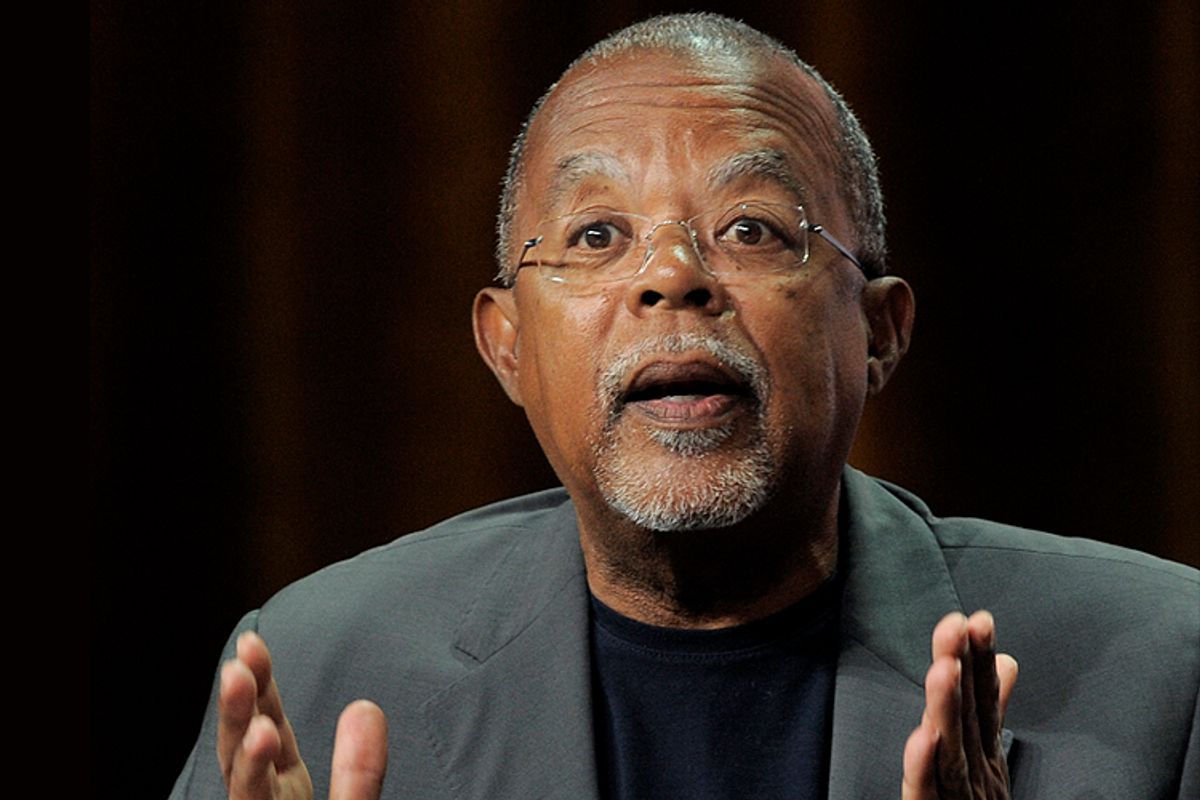

Henry Louis Gates is on a mission to change how race is taught in America.

The Harvard professor of African and African-American studies is among the most public thinkers on the issue of race in the nation; his stature is only set to grow with the PBS series "Many Rivers to Cross," which begins airing on Oct. 22. The six-part series considers the black experience in America from many angles, starting from the beginning of the North American slave trade.

Gates intends the series to help teach race in what he considers to be an utterly ineffective school system; he's quick to cite studies indicating that black history is not being taught well in schools. Indeed, in a conversation with Salon, Gates indicated that he believes certain states ought to mandate black history education in schools.

But the real conversation Gates wants to be having is one about class. He spoke to Salon about the degree to which the end of legal segregation led to the splintering of the civil rights movement as well as to further inequities on a national level, and what the government needs to do to ensure a fair shot for all citizens. Here's a hint -- it's not a "conversation on race" of the sort convened after Gates was arrested trying to enter his Massachusetts home. In fact, he hates the term. A meaningful conversation, Gates told Salon, "can only happen if nobody uses the worlds 'conversation about race.'"

I really enjoyed watching the first episode.

You know, I just watched it myself, with my girlfriend. And I really liked it.

Were you surprised that you liked it? Do you sometimes not like things that you’ve done as much?

No, no; I always like them. But I always wait. You know, I write the script, I’m the host, I’m the narrator. But seeing the final package is always a completely different experience. This one I put it off, put it off, put it off and finally said, “OK, I’m going to watch it.” So my girlfriend and I watched it this morning, in preparation for you and I was really delighted. It was just great.

I’m kind of curious the degree to which you think we as a nation -- especially students -- are at risk of forgetting slavery. I wonder if this series has to exist and things like it have to exist to remind people?

I think of this as a black history series for your generation. A generation that didn’t see "Roots" when it was being shown every night creating a national phenomenon. A very cosmopolitan generation, technologically savvy. Less concerned about race as an individual basis than any generation before it. And more integrated – socially integrated, whether it’s images on television or as the definition of American popular culture adds the African-American element as its lingua franca.

But on the other hand, schools are failing in terms of teaching the black experience. We don’t have to be anecdotal about these things. The Southern Poverty Law Center recently issued a report – and you can Google this – on how well the civil rights movement, just the civil rights movement – you’d think with Martin Luther King Day and February as Black History Month, how many times do you hear “I have a dream" in the month of January and February? A million times – you'd think that the one thing that the schools would be doing right, and covering adequately, would be the civil rights movement, right?

Wrong. Only three states received an "A": Alabama, Florida and New York. And only three even received a "B": Georgia, Illinois and South Carolina. For adequate coverage of the civil rights movement. Thirty-five states received an "F," including the great state of California. You can imagine if they did a similar survey of slavery, the results would be even worse. Part of the reason for that is that I don’t think teachers have had, I know they don’t have one DVD of a series that they can use for their multimedia element. And that’s because no one has tried to do a comprehensive survey of African-American history since 1968, since Bill Cosby did “Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed,” which I watched with my parents in Piedmont, W.Va., when I was 17 years old. And that’s what inspired me to go to Yale and take a black history course, in fact, the following year.

Teachers need tools to integrate the content about the black experience. And this series is the only one crazy enough to do what turned out to be 500 years of African-American history. Starting, as you saw, with Juan Gurito, first black man to set foot on what is now Florida in 1513 with Ponce De Leon looking for the fountain of youth. All the way to Obama’s, President Obama’s second inauguration. Heretofore, teachers would have to use "Eyes on the Prize," which is on the civil rights era, and "Slavery in America," and "Freedom Riders" by Stanley Nelson, and something on the Harlem Renaissance. So what I decided to do was tell the story in one series using salient stories – 70 stories over the six episodes, which were exemplary of the whole larger experience. So I worked for seven years on the series, and we gained 30 or 40 stories. When we started, we had a list of the indispensable, canonical stories that any series would have to tell. [laughs] And so we spent years whittling down the stories to be the essential ones, and that’s what we came up with.

I wonder if there will come a point when the kind of scars on the nation from slavery are gone. When the stain on the national conscience is ameliorated. It seems to me that we’ll never be past it! It’s too horrible.

Well, do you think the pains of the Civil War have been ameliorated or abated yet?

I don’t, personally.

Well you know, that’s it. Whenever I think they have, all I have to do is look at someone on TV from the right who is from the South, who is still metaphorically fighting the Civil War. Or when you see the people lifting the Confederate flag, or 1,001 other manifestations that it’s still an open wound. What I hope we can achieve is more distance on it. And I think that’s what you’re implying, what you’re getting at -- that we can see it more objectively without blaming people. Or holding a descendant of someone who fought for the South responsible, if you’re an African-American, for slavery or for the suffering of one's ancestors. If we could chalk it up to history the same way we do terrible things in each era of history -- are people actually bleeding about the Seven Years' war or the Hundred Years' War, the War of the Roses in England? You know, OK, we’ve moved on 500 years later.

I think one of the other reasons that I wanted to make this series, is that we’re living in the time – the best of times and the worst of times – we have a black president, statistically the black upper middle class has quadrupled since 1968 when Dr. Martin Luther King was killed. But on the other hand, the percentage of African-American children living at or beneath the poverty line is just slightly less than when Dr. King was living. And we have more black men in prison than Martin Luther King, Du Bois or anyone else could have ever imagined. We have this huge black-white wealth gap, but we also have a black-black wealth gap between the black haves and have-nots. So how did we get to this curious place? That’s why I wanted to make this series and the roots go back for that 500 years with a lot of twists and turns. I wanted to create a tool. It could be used in a classroom to facilitate a true conversation about race, we could talk about what I mean about that. I wanted it to be an explanatory agent, in terms of helping us understand the paradoxical contradictions that we have today in our society between more black people doing well in every field and so many black people doing terribly. How did we get here?

Does it drive you crazy when people refer to ours as a post-racial society?

It drives me nuts! I can’t even imagine what it means. I don’t even want to be in a post-racial society. You know, I’m a professor of African studies and African-American studies, and I do very popular PBS television shows, in terms of excavating people's roots ...

What’s your heritage, by the way? Your ancestral heritage? You’re Italian?

Yes.

And it’s very important. It was very important to Mario Batali when I introduced him to excavated ancestors of hundreds of years. It’s crucial. I don’t want there to be a time when we’re colorless. I just don’t want your Italian heritage and my African heritage and Irish heritage, in my case, to be used to limit your possibilities or mine to limit my possibilities. When you could wear your ancestry, your sexual preference, your gender orientation, your religion, your color, what have you – you can wear it without penalty. And that’s what, that’s what situation we haven’t achieved in this country. It still matters that you are black or gay or a woman or Jewish, and I’m sure Italian, in some contexts. In terms of the presidency, it can be gotten rid of by waving a wand, or even by electing an Italian president, a Jewish president or a black president.

How would you change the manner of how history, and particularly racial history, is taught? If you had the opportunity to put into place your own curriculum all across America, what would you do?

I would do two things. One: African-American history would be completely, thoroughly integrated into American history. That’s not yet done sufficiently. So that the story would be much more complex. We need the story of George Washington, but we need the story of his slave at the same time. Which is the story we told in Episode 1. Metaphorically, if you have "American Bandstand," you need to have "Soul Train," which is what we do in Episode 6.

There’s too much whitewashing of our founders, for example. George Washington has more slaves than any other president, than the first five presidents, and didn’t free them until his deathbed. We need to tell these stories without blame and show how complex our heroes of American history were. The second thing we need to do, I would like to see, in some states, black history courses mandated. I would like to see that done. In part because black history has been excluded for so long, and because it is such a fundamental part of American history, that we have to do a dramatic corrective. So I would like to see a high school class -- I wouldn’t do it until then -- a high school class on African-American history mandated throughout the country.

A lot of organizations like the NAACP seem to have lost some of their status as thought-leaders. They’re not where people turn for information or for advocacy first, necessarily. And I’m wondering if a certain sense of solidarity has been lost and if that’s a bad thing.

I think that the problems of race and class have been, are so inextricably intertwined -- but because of segregation, because of legal segregation, our political organizations only identified race as a cause. So once segregation was dismantled with Brown v. Board of Education, and the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1965, et cetera, there was a naive belief that all African-Americans would plunge headlong into the middle class. But that’s obviously not what happened. And as I’ve said and you know, affirmative action created an upper middle class, which I’m a part of, and all those people were left behind. So I think that the leaders of our traditional civil rights organizations have been scrambling for a new analysis.

Because if you think about it, since slavery ended, all political movements have been about race. If you think about the economics of the Black Panthers but they were annihilated, right. There were black socialists in the 1920s under A. Philips Randolph, and there were black Communists. And I’m certainly not advocating Communism or socialism, but they were at least talking about the role of economics even if they didn’t get it right. Martin Luther King only at the end was talking about it -- despite the fact that the March on Washington was for jobs, and equality, specifically, in employment. It was only at the end that he was realizing that race was only part of the issue. I would say that the traditional organizations like the NAACP, which was under the great leadership of Benjamin Jealous, and Marc Morial and the Urban League, etc. They are reformulating the agenda and they are still in the process of doing that.

Have we lost unity? Yes. I think that the black community, like other ethnic communities, has 100 percent unity when it comes to a race issue. When it comes to voting in a black president, it was overwhelming, 95 percent unity. When it comes to the class differences within the race, there is a lot of variation in lifestyle, possibility, where your kids go to school, how they’re treated where you live. Whereas before you could have a doctor and a maid living next door to one another because the neighborhoods were segregated. So yes, to answer your question, the black community has become fissured in ways that generations before the 1960s couldn’t imagine. Culture -- shared cultural values -- creates more of an illusion of unity, which is belied by economic differences, life choices, responsibility. One of the places in my series to show that there has always been a variation, a lack of unity in the black experience. From the time the first few black people showed up, some were free and others were slaves. And that’s a difference between 1513 and 1528, so I wanted to show that diversity.

Nobody talks about how there are more black Americans than there are Canadians, but everybody talks about “the black community.” Nobody in their right mind talks about “the Canadian community” as though all Canadians are going to speak with one voice and one mind. But on the other hand, that’s how we talk about black Americans. And black America is just too diverse for that. I think that because of that and because of the economic diversity today, there is a lot of nostalgia for the world of segregation, when it seems like the community was more unified. But the challenge is for our political leaders to formulate an agenda that takes into account race and class. And that is what we’re seeing today.

Can I go back to the little riff I wanted to make about the conversation on race?

Sure.

Everyone talks about the "conversation on race." Every time we need a "conversation on race." The only place where a meaningful conversation with long-term impact can happen is in the schools, and can only happen if nobody uses the words “conversation about race.” What do I mean by that? Schools are the vehicle to create citizenship and you learn it osmotically. Nobody says, “Daniel, I’m going to teach you to be a good citizen.” You learn the Pledge of Allegiance, "My Country 'Tis of Thee," "America the Beautiful," George Washington chopped down the cherry tree and never told a lie. All of this is how we become citizens. And what’s been left out of that conversation is race, honest conversations about race. But not feel-good talk. I’m talking about [the slave] Harry Washington and George. I’m talking about the economic role of slavery in the creation of America. The fact that the richest cotton-growing soil happened to be inhabited by five civilized tribes, what they called themselves, and that had to be exterminated, removed and or exterminated for the greatest economic boom in American history to occur. The Trail of Tears, the cotton boom from 1820 to 1860. I’m not talking about politically correct history, I’m talking about correct history. I just made that up -- I have to write that down.

That’s how to have a conversation about race, when it happens every day, it happens every day osmotically. Just in the atmosphere, as a normal part of the discourse in the classroom talking about shaking up America. Instead of – I’m 63, and the only black history we ever got was called “Slavery Day” and the teacher would say, "Well, there was slavery and it was the best thing to happen to you people. You were eating each other and swinging through trees." I went to an integrated school in 1956. And it was embarrassing, I didn’t know anything about black history until Bill Cosby’s in 1968, really. So I want this series to contribute to real conversation in the classroom precisely by making it unnecessary to use those specific words.

I’m curious about the tendency of white people to point at exceptional African-American celebrities, like Oprah Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Barack and Michelle Obama, Will Smith, as examples of people who made it, and to refer to them as “good examples.” I find myself wincing when I hear rhetoric like that, because the implication is shaming in a way to every African-American who isn’t Oprah Winfrey.

Many of those people you mentioned are friends of mine and I’m very happy for their success. But their success is not typical of the African-American experience. And there have always been exceptions. Remember that first episode, I talk about Anthony Johnson? He’s a slave who gets freedom, he gets married, he and his wife get their freedom. He accrues 250 acres and even, in the year 1864, takes a black man to court who was working for him, proving that the man is his slave and not an indentured servant. So there have always been exceptions from the get-go.

That’s a handful of superstars and millionaires you’re referring to. But even if you look at that black upper middle class that has quadrupled since 1968, it’s still exceptional. It’s still a small group of people and it still has much less wealth than its white socioeconomic counterpart. What we all need to strive for is a bigger middle class that's more integrated. So we need to focus on jobs. We need a jobs bill. We need to figure out how to reform vocational education so that it produces people with the skills needed for a 21st century highly technical economy. And that’s not what we’re doing right now.

I don't know if you saw protesters waving the Confederate flag in front of the White House. Will the Republican Party make it difficult to implement a jobs bill of the sort you propose, one that would help particularly the black middle class or lower middle class, because of a sort of inherent racism? Can they outgrow that in a matter of time?

I would say I know many Republicans who aren’t racist, and I wouldn’t want anyone to think that I was equating being a Republican with being a racist. But I know that the criticisms of Obama are definitely rooted in anti-black racism. And I think it is incumbent upon both the left and the right to see part of the problem and figure out how to help poor people, how to help working-class people, whether they’re black or white. Even affirmative action. I grew up with poor white people in the hills of West Virginia, I want affirmative action applied to them as well. When I started at Yale in 1969, affirmative action was a class escalator. And I want to see affirmative action be a class escalator for everyone, not just black people.

But again, it goes back to the classroom. You can’t just call these people out and say, “You’re a racist,” and expect them to change. In children, you get them in the classroom in first grade and we’re teaching them the nobility of the human spirit in black faces as well as white faces and not drawing attention to it; we’ll be showing them through a truly integrated curriculum that is the last great hope for the obliteration of racism in America. Because American popular culture has been integrated since the 1950s and 1960s, and under hip-hop in an extraordinary sense. It’s not like white racists don’t listen to black music, or cheer on black athletes, or attend movies with black characters. There’s a kind of switch that turns off; the switch is called economic fear. The people are threatened, they’re afraid for the future of their children. If you’re afraid. If I have I pie, and I have enough to go around, Mr. D’Addario, you are welcome to come to dinner. But if I think that you eating my pie is going to keep me from eating it, or my children, I’m sorry. Not only are you not going to come to dinner, but I also might be talking bad about Italians.

And that’s what happens. Under Lyndon Johnson we had guns and butter, we thought we had enough prosperity to put everybody in the middle class, and as soon as that dream fell apart, people once again started demonizing one another. Slavery was about economic relations, it was easy to demonize a group of people who looked so starkly different. As scarcity increases, so will racism. So will anti-Semitism. So will homophobia. That’s why schools are essential in countering the kinds of attitudes, unfortunate attitudes, children pick up in their living rooms from their parents.

Shares