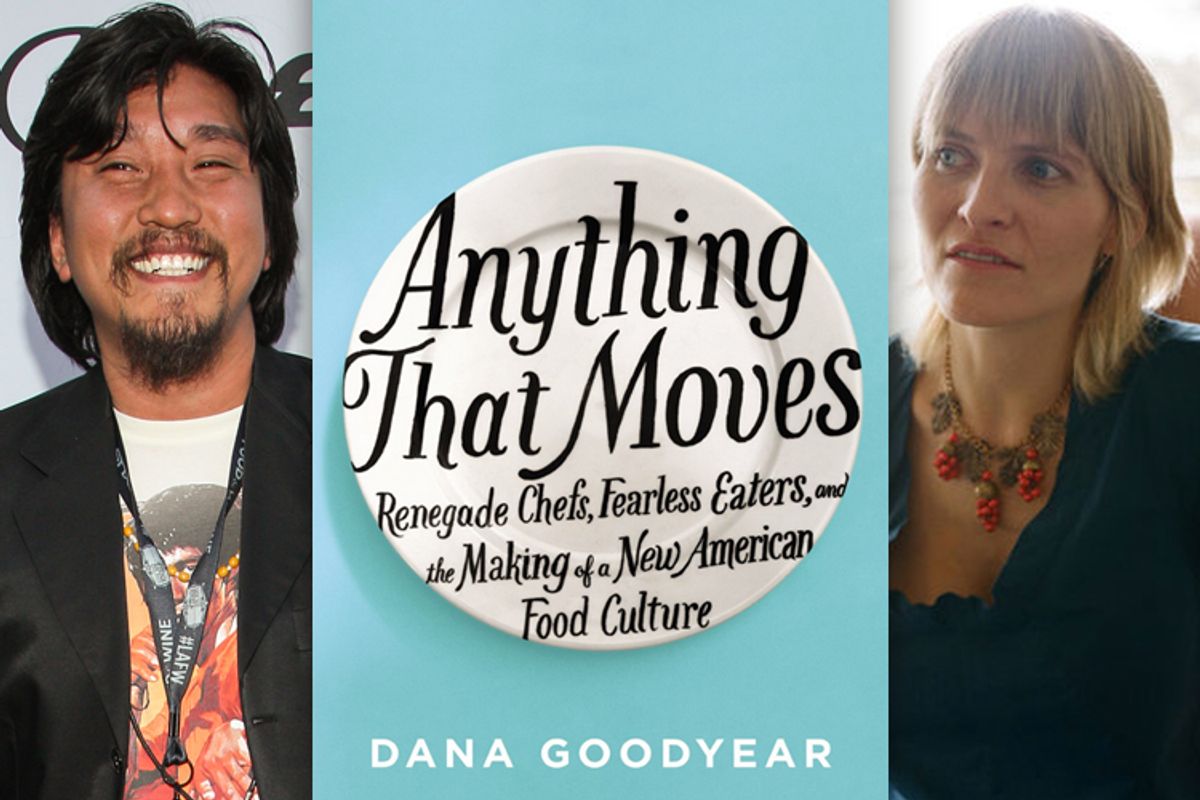

Dana Goodyear is the author of the much anticipated "Anything That Moves: Renegade Chefs, Fearless Eaters and the Making of a New American Food Culture," a journalistic window into the current food movement of extremely fringe groups pushing the boundaries of what we deem as edible.

I’m in Los Angeles for one night and the New Yorker writer is nice enough to meet me for dinner and a conversation. Considering the subject matter of the book, it seemed a bit wimpy for us to meet over caffè lattes, so we head to a traditional Oaxacan restaurant buried deep in the heart of Koreatown that is known for their crispy grasshoppers.

The evening starts with a Mezcal served in a gourd with a side of sliced oranges and chili powder.

Edward Lee: You are going to have to pronounce this restaurant name for me.

Dana Goodyear: Gay-lah-GHET-sah.

Yes, Guelaguetza and we are eating grasshoppers or chapulines, which are very crispy and delicious. Thanks for coming and having dinner with me. And thank you for all these dishes you ordered, the mole, the goat tacos and the chile rellenos are all perfect. First of all, this is a fascinating book and it’s an incredible window into the underground foodie world. So my first question is simply how did you gain access to this world?

I find that people in the food world are amazingly willing to talk about what they are doing even when those things are quasi-legal or taboo. I don’t know if that is the hospitality culture of dining or if it’s the thrill of presenting something that hasn’t ever been presented as food or if it’s the culture of the current food movement and its outlaw sensibility. I had to be careful occasionally and take out the names of people who were perfectly willing for me to put their names in, because I felt like they might get themselves into more trouble than they realized. But people were really eager to share their secrets with me –

Even knowing that you were a journalist and you were writing about them.

Oh yes.

So their ego trumped potential jail time?

I don’t think it was ego. I think it was the thrill of saying: You can eat this and if you’re not allowed to eat this, you should be. The people that were the most anxious were the raw dairy people because the stakes there are pretty well established. I was writing about a community that had been recently busted and so there was a lot of secrecy and credential checking. At one point somebody asked me if I was a government agent.

(Dana orders a hot chocolate and I order a flan)

The raw milk people are just one fringe group out of many that you write about in your book, but there are many from very diverse backgrounds. The common thread between them all seems to be a sentiment of anti-government. You also mention books like Upton Sinclair’s "The Jungle," so is there a historical precedent for this kind of thinking or is this something that is brand new?

Thank you for perceiving that common thread because that really is what unites these disparate people. Each group champions a different, very specific approach to eating, but what they have in common, and what makes it a movement, is the sense that we can be eating and should be eating more broadly than we are now. There is a notion that American sensibilities, which are formed in large part by American laws, need to be changed. The anti-government sentiment is strong both among marginal groups doing things that are blatantly illegal and among very high-profile chefs who are saying it’s absurd that I can’t serve foie gras in my restaurant.

Do you take a political stance in the book?

I don’t personally. I see the value of regulation but I also sympathize with the frustrations of a lot of these people. For me, I look at it case by case and in some instances, the laws do seem onerous or overly sensitive to certain risks that aren’t so great while completely ignoring other risks. So it’s inconsistent. But the great irony around "The Jungle," which was a novel, is that the regulatory framework that was set up in 1906 as a result of its revelations enshrined big business in food. It gave us the official food culture that this current movement is fighting against.

Still to this day?

Yes. What defines this new period of obsession with food is a sense of “how did we stray so far from the original intent of these laws?”

There are so many diverging groups that you interview from all walks of life, as you mentioned. But they don’t seem like they communicate with each other. So is it accidental or intentional that all of this is happening right now?

You are right, they don’t. Sometimes they are at odds with each other. But I see the occasion for this movement as an anxiety about America’s future. It’s related to what people have come to understand as the unsustainability of the American way of eating. There’s this interesting flip-flop where the avant-garde of the food movement is now starting to look at, and emulate, long culinary traditions that have come out of poverty. It is fascinating to me that the dominant ideas in fine dining now derive from poverty.

The last 10 years have seen America become insecure about its place in the world and its role in history. The rise of the food movement during this period of insecurity is not a coincidence. I think there’s an emphasis on being personally resourceful and even though it sounds ridiculous to talk about that in terms of what you might eat on a $250 tasting menu, it’s being reflected there. Food is a lens for culture.

It’s interesting you say that because as I read your book, well, it’s obviously about food but it’s about so much more, it’s about the culture we are living through right now. Is this culture more political, more artistic or a combination of both?

I think for diners, it is about crafting an identity around food which we have not really had in a mainstream way in this country. So there is a mass movement of people who identify themselves through their food preferences or even just that they prioritize food – that’s where we get this idea of being a foodie.

But the people in your book are not just foodies.

Of course, that’s just one aspect of it. But that speaks to the democratization of this interest. It’s not just the fat cats who are into food. It’s a youth movement to a large extent. The chefs are as curious as the diners are. It is their duty to show people that there is more out there.

Then are the people in your book just harmless foodies taken to an extreme or is there something more subversive, something dangerous, dare I say, revolutionary?

I think the revoultion may already be going on. Aesthetically, the things that people are valuing in food are all pre-industrial. They are either that period right before 1906 -- the handcrafted, pickle-making scene -- or they are pre-domesticated agriculture. I do think there is an attempt to reverse the processes that seem to have gone off the rails.

In every movement, you have the radicals that exist on the fringe and then what makes it to the mainstream is usually a watered-down version of the original concept. What of this movement will survive or make it to the mainstream?

It’s always dangerous to predict the future (laughs). But the reason I focused on these extreme groups is that in them you can see many potential futures. It’s not a unified front but these are people who are all doing things that I think are likely to influence the way the mainstream eats even if it’s just in their attitude.

The two obvious candidates for mainstream foods of the future are insects and organ meats. Insects make logical sense, and yet you can’t reason with someone who thinks eating them is disgusting. Eventually, I do think that insects will follow a sushi pathway toward acceptance.

But there’s a production problem with insects because for Americans, insects are not traditionally food so we don’t have USDA approved insects. But we do have lots of USDA approved organ meats. Because we’re already fattening up the pigs, why not use their ears? We’ve been sending those undesirable parts to the dog food factory for a long time. It took a few renegade chefs to transform their reputation. In the last five years, we’ve seen pig ears go from being a shocking conversation piece on menus in L.A. and Chicago and Portland and New York, to something really normal on menus everywhere.

If it becomes mainstream, does it run the risk of no longer being hip?

DG: Probably, but look at sushi. It’s everywhere but I still love to go get sushi. And I can get it at my mom’s favorite grocery store in St. Louis. There will always be something else, something more extreme that will be celebrated by cutting-edge chefs.

Were you ever scared? There were moments in the book where I felt like you were in covert situations surrounded by these intense characters who operate outside the law. Was it all just for the sake of food or did you ever feel an undercurrent of violence or anger that scared you?

What I felt was an undercurrent of unacknowledged risk. Or risk that there was no consensus about.

There’s one scene where people are eating scorpions for the first time not knowing what the risks are and I’m not sure if I would have taken a bite.

Oh, and I didn’t.

So was there any pressure on you as an outsider like: Either you eat with us or get out.

No, it wasn’t menacing like that. But there are some hazing rituals, and eating is a test. What scared me I guess was the diversity of opinion about what was safe. And that goes back to the reason we have laws about what is safe and not safe to eat. In the world I write about, if there are safety risks, they are often considered thrilling.

In writing this book, did it shape your own personal diet?

I used to have this attitude of “when in Rome, try it” but I learned enough about some of the global ecological risks of eating that way that I now regret some my choices.

Like whale?

Yes, that’s the main example. I ate whale with Icelandic friends who were encouraging me to do it, but once I learned more about it, I regretted it. I also didn’t like it. (laughs) Ultimately taste is so niche and so personal.

Last question, if your book could have a scratch ‘n’ sniff on its cover what would it be?

DG: It’s got to be Laurent Quenioux’s marijuana pesto congee with monkfish cheeks fried in “green” coconut oil: like a Jamaican beach, pot smoke and Bain de Soleil.

Shares