On July 2, 1964, six months after [Norman] Rockwell’s painting of a heroic black girl walking into a white school appeared in Look, the Civil Rights Act became law. Finally, there could be no more separate lunch counters or hotels or theaters, no more discrimination in public places such as schools and libraries, no more inhumane banishment to the bumpy back row of the bus. This is not to say that the new legislation was universally acclaimed. The South was predominantly Democratic, but Democrats there bore little relation to the ones up north. They were so uncomfortable with the Civil Rights Act that they were threatening to vote President Lyndon Johnson out of office in November.

That summer Rockwell was assigned by his editor at Look to paint portraits of the president and his opponent for an Election Day issue. He flew out to San Francisco in mid-July, when the Republican National Convention was underway at the Cow Palace. Barry Goldwater, the Arizona senator and hero of conservative Republicans, sat for his portrait at campaign headquarters in his trademark horn-rimmed glasses. He had opposed the new civil rights law, claiming it violated the sanctity of states’ rights, a phrase that many considered a lame cover for institutionalized racism. “I didn’t vote for him,” Rockwell later said of Senator Goldwater, “but he was a very cooperative model.”

That same week, on July 16, at 11:30 a.m., Rockwell was ushered into a portrait session with President Johnson at the White House. It was their first meeting. It was held precisely two Thursdays after the president had signed the Civil Rights Act into law and Rockwell found him impatient and crotchety. The president appeared dismayed when Rockwell asked for an hour of his time, saying the most he could spare was twenty minutes and instructing Rockwell to “get cracking.” So Rockwell proceeded much as he always had, sketching away, making amusing comments, instructing his subject to look this way or that while a photographer took pictures from every angle. “I decided to do the best I could, but he was just sitting there glowering at me,” Rockwell recalled.

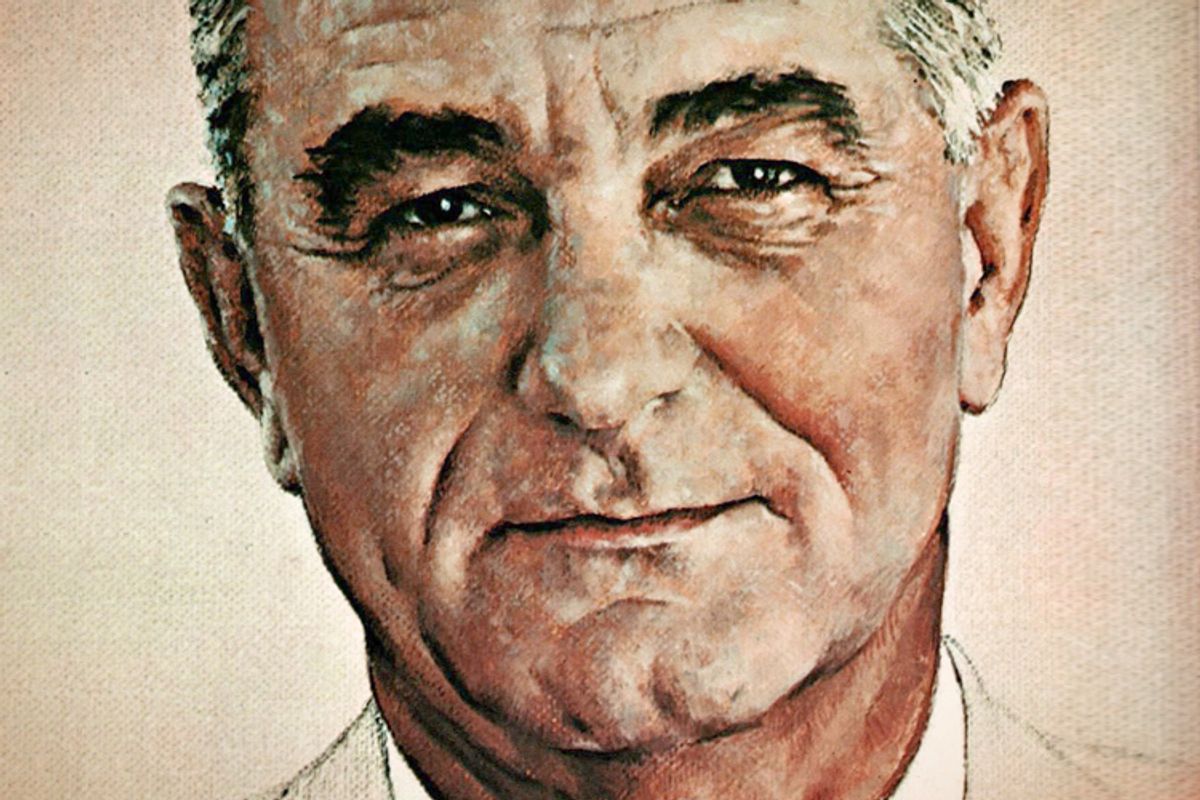

With only a few minutes left, Rockwell tried to reason with his subject. “Mr. President,” he said, “I have just done Barry Goldwater’s portrait and he gave me a wonderful grin. I wish you would do the same.” So the president indulged him, or at least tried. For the last minute, he forced his mouth into a manifestly fake smile, “like he was competing for the Miss America title,” as Rockwell later recalled. The portraits appeared in Look, on inside pages, on October 20, 1964, two Tuesdays before Election Day. FULL COLOR, the magazine boasted with uppercase excitement on its cover, as if color photography, which was still fairly new in popular magazines, somehow mirrored the revolution in sexual mores and offered a lusty antidote to the camouflage of the gray-flannel fifties. The portrait of Johnson, with his long face and droopy hound dog ears, cannot be said to have rehabilitated the tired tradition of the presidential portrait. But it is probably as appealing as a portrait of Johnson can be: psychologically astute, devoid of pomp. He is shown from the neck up, a middle-aged Texan with deep creases around his mouth, a hint of shadow beneath his cleft chin, his thinning hair combed straight back. Instead of gazing assuredly at the viewer, as American politicians are almost professionally obligated to do, he looks off to the side, a bit sadly. This is LBJ not as the champion of the Great Society, but as a man who feels anxiously aware of the gap that separates his proposals for reform from the enormity of the problems facing the country.

Ever since painting his first portraits of presidential candidates (Dwight Eisenhower versus Adlai Stevenson) for The Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell had always presented the paintings and accompanying sketches as gifts to the candidates, by which time they were no longer candidates but winners or losers. President Johnson thanked him for the portrait, however perfunctorily, in a letter composed on September 15, 1965: “I am glad to have the original of the painting that you did of me last year.”

None of this would suggest that President Johnson loved Rockwell’s portrait of him or enjoyed the ordeal of posing for it. But he did in fact love it, as he realized in an art epiphany six weeks after receiving the gift, when an established painter named Peter Hurd unveiled for him yet another portrait—the so-called official presidential portrait. Hurd, a native of New Mexico known for his hilly, adobe-colored scenes of the Southwest, was part of the exalted Wyeth clan. He had studied with patriarch N. C. Wyeth, the great book illustrator based in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, then married his daughter, Henriette, the sister of Andrew Wyeth and herself a painter.

Much like Rockwell, Hurd felt exasperated by the time allotted, or rather not allotted, for his portrait of President Johnson: he was given only two sittings. One took place at Camp David, the retreat in Maryland, where the president was posing in a chair when his head slumped onto his chest and he appeared to nod off for a few minutes, depriving Hurd of any view except for the pomaded strands of gray hair combed across the top of the presidential scalp.

At the end of October, Hurd and his wife transported the painting to the LBJ ranch in Texas hill country for a private unveiling. Truth be told, it is not a great painting—a three-quarter-length affair, in which the president looks mannequin-stiff as he stands outdoors in a dark suit, gazing off as if trying to read cue cards located just beyond the left edge of the painting. He is holding a book whose generic title (History), visible on the cover, remains unaccompanied by any hint of the book’s author, perhaps because this is a book that no one ever wrote. Behind him, in the distance, the white dome of the U.S. Capitol glows against an early evening sky streaked with purple. President Johnson did not hesitate to share his opinion of the painting with the artist. He took one look and pronounced it “the ugliest thing I ever saw.” When Hurd asked, “Just what do you like, Mr. President?” Johnson rushed to his desk and pulled out from a drawer an old Look magazine, shouting, “I will show you what I like!” Then he waved the portrait that Rockwell had done.

Hurd countered derisively, “I wish I could copy a photograph like that.” The president insisted the portrait was not a copy of a photograph that he had in fact posed for it. He added that Rockwell had managed to produce it after only one, inordinately efficient twenty-minute audience with him, which is perhaps what the president liked best about the portrait.

Lady Bird, in the meantime, took it upon herself to provide Hurd with what she believed were well-founded criticisms of the painting. She recalled in her diaries “a gruesomely uncomfortable half hour” in which she proposed several major changes. For one thing, the painting stood four feet high—too big in Lady Bird’s estimation. She found the sunset garish and was particularly bothered by the portrayal of the president’s hands, which she felt were not the “gnarled, hardworking” presidential hands she knew and loved but a bland simulacrum. Hurd, she noted, “was the first to admit that the body, and especially the hands, were not good, because he had not had enough sittings.” Her verdict was that Hurd should go back to his studio and make a smaller portrait in order to omit the president’s hands altogether. Then the Johnsons would look at it again.

For all his stated affection for Rockwell’s portrait of him, President Johnson was willing to part with it for political gain. He used it as a chit to please a supporter. Unknown to Rockwell, Johnson regifted the painting in 1966 to a friend in Texas. “Norman Rockwell sent me a portrait I thought you might like to have,” he wrote that April to Robert Kleberg, Jr., who owned the King Ranch and had just embarked on a dubious plan to establish a wildlife refuge stocked with deer and nilgai antelopes on the site of the president’s own birthplace. “I am sending it to you, suitably inscribed, for your home.”

Peter Hurd, in the meantime, eventually lost interest in undertaking a second portrait of the president. He decided instead to put the original one on public view, seeking the small satisfactions of revenge. The story broke on January 5, 1967, in a women’s page feature in The Washington Post, and was quickly picked up by newspapers and magazines all over the country. Speaking to reporters by telephone from his ranch in New Mexico, Hurd cheerfully denounced the president’s behavior (“very damn rude”). It turned out that a majority of Americans sympathized with Hurd and agreed that the president had treated him shabbily. The story of the callously rejected portrait seemed to confirm LBJ’s reputation as a man who was insulated from the public and had no patience for opinions other than his own, not least when the opinions came from his various advisers who thought the country should get out of Vietnam.

Hurd was happy to expound on his art and his technique for his new following. He explained in interviews that he favored the quaintly ancient technique of egg tempera. Consequently, his portrait of President Johnson had taken him a total of “400 hours,” the implication being that the quality of a painting, not unlike homework, is directly related to the amount of labor expended on it.

The most irksome part of his experience with the President, Hurd arrogantly told The New York Times, was having to hear his work compared unfavorably to that of Rockwell, whom he dismissed as a “good commercial artist.” It might seem hypocritical that Hurd, who worked in the realistic style of his hero N. C. Wyeth and himself did an occasional portrait for, would malign Rockwell as a commercial artist. His comment suggests that the Wyeth clan considered itself artistically superior to Rockwell, who had never denied his status as an illustrator or tried to escape the stigma. There was no Helga in his life, no secret desire to forsake illustration for more reputable kinds of painting.

Moreover, Hurd maintained in the Times that Rockwell copied from photographs, whereas “I’ve never learned to copy photos.” The Washington Post carried a similar accusation: “Rockwell’s genius lies partly in being able to turn out slick, speedy, glossy copies of photographs in record time to meet magazine deadlines, Hurd insisted.”

Sadly, no one came to Rockwell’s defense, including Norman Rockwell, who had never bothered to answer his detractors over the years. But someone, anyone, might have pointed out that he did not copy photographs. Rather, he used them to lend greater credibility to his fictions.

Rockwell was unable to express whatever resentment he may have felt over the incident. He almost never went on record criticizing another illustrator and he was not about to pick a fight with the brother-in-law of his colleague Andrew Wyeth. In fact, he actually defended Hurd in his one public comment about the incident. In the summer of 1967, speaking at the National Press Club in Washington, he blamed the affair of the rejected portrait on the White House. President Johnson may have considered Rockwell’s portrait of him the epitome of artistic excellence, but, as Rockwell told the audience with his usual self-debunking humor, “President Johnson is a terrible art critic.”

Excerpted from "American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell" by Deborah Solomon, published in November 2013 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2013 by Deborah Solomon. All rights reserved.

Shares