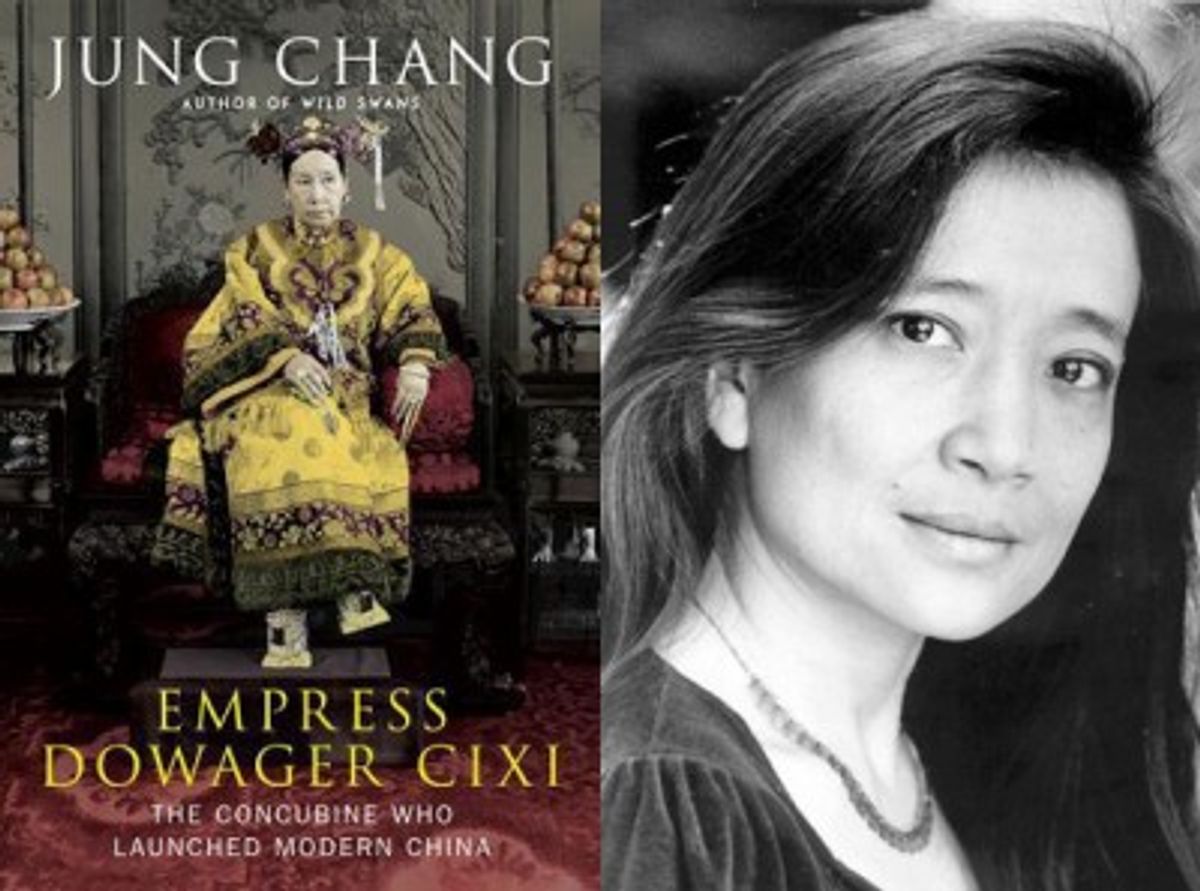

Jung Chang's new biography Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013) recounts the remarkable life of China's Empress Cixi (1835-1908), who ruled China for 47 years and helped bring it into the modern age.

Working from newly available historical documents, Chang intends to revise traditional notions of Cixi as a reactionary despot and the era in which she ruled. Assessing Empress Dowager Cixi for the New York Times Book Review in October, Director of Asia Society's Center on U.S.-China Relations Orville Schell wrote that Chang's "extensive use of new Chinese sources makes a strong case for a reappraisal" of Cixi's role in China's development. (For another noteworthy review, see Rahul Jacob in India's Business Standard.)

Chang's previous books are Wild Swans (1991), a family history that sold more than 10 million copies and was also banned in China, and Mao: The Unknown Story (2005), co-authored with her husband, British historian Jon Halliday.

Chang joins Orville Schell for a discussion at Asia Society New York tonight, November 12. (For those who can't attend in person, the program will also be a free live webcast on AsiaSociety.org/Live at 6:30 pm New York City time.) Chang's book tour will also take her to Asia Society Texas Center on November 17 and Asia Society Northern California on November 18.

Chang spoke to Asia Blog by phone just prior to her Asia Society New York appearance.

What attracted you to the Empress Dowager as a subject?

I first got interested in her when I was researching Wild Swans. I realized it was she who banned foot binding. I had thought, somehow, foot binding was banned by the Communists because that was what my education told me. So that got me interested. And then, you know, after I wrote Wild Swans, after I wrote Mao: The Unknown Story, when friends suggested writing about the Empress Dowager, I looked her up on the Web and I found that her reputation was as bad as, you know, my brainwashing days when I was in China. The little bit I knew about her was completely different than her reputation. That made me feel that I could find new materials and have new ideas. I don't want to write things that everybody agrees on. In other words, there is controversy about her — I like that.

How did the Empress Dowager's character become so distorted and maligned later in history?

Well, three years after she died, China became a republic. The republicans wanted to malign her. Well, not just the republicans — the rulers after her, the people in power after her, didn't want to see her having a good reputation because they wanted to say you know, she's made a mess of China, and it fell on them to rescue China from her.

How did Cixi improve the lives of women in China?

Apart from banning foot binding, she gave women education, she released them from homes. She encouraged them to have education. And she basically espoused women’s liberation. So much so that in a magazine in China in 1903, people were declaring that the 20th century would be the "century of women's rights" (女权).

Do you see her as a role model for Chinese women today?

No. I don't think she's a role model. She was an empress — the Empress Dowager. She came from a medieval China; she was capable of immense ruthlessness, I mean, she was a politician. When she sent an army to reclaim Xinjiang, the expedition was extremely brutal. We know she poisoned her adopted son along the way. You know, she was a medieval figure. My book also describes her transformation from this medieval empress, or imperial concubine, into a modern person — her own transformation as well as the transformation of China. I think, you know, she has a certain quality I think people can learn, she had a conscience, she did care for her people, she didn’t like bloodshed, et cetera. One can be appreciative of these qualities. But role model, I mean, (laughs) to be the absolute ruler of China?

But don’t you think there’s a shortage of women in Chinese politics?

Yes. I think, yes, probably. I don’t know the selection process for the leaders. I certainly would like to see more female politicians in China.

Do you think there are prospects for more women entering the top ranks of Chinese leadership in the near future?

Yes, I think that's the trend in the world — to have more and more women in the decision-making circle. I think probably that's also the road China will be embarking on as well.

Do you think today's Chinese leaders could learn something by studying the leadership of the Empress Dowager?

The thing is, I didn't write a political fable. I just recorded her life. As a book, I think readers can take away whatever is relevant to them. I don't know what people will take away from Empress Dowager Cixi, nor do I have this intention for them to take away a certain message. My motto about message in a book is: flowers in honey, salt in water. The messages have disappeared, but the flavors are everywhere. My book is not a message book.

In terms of process, how was writing this book different than your last one?

It's different from writing about Mao in the sense that with Mao, my husband Jon Halliday and I spent 12 years researching and writing. The main problem was the sources, the documents. Because there was a lot of cover-up — there still is — about Mao. So we had to dig up every bit of information. But with the Empress Dowager, the documents have all been made available: the scholars, the archivists in China and the rest of the world have been doing a lot of work compiling, photocopying, editing, making complete works of this and that, releasing court documents, some even digitized, so they're relatively easy to get a hold of. So I can, you know, sit at London at my computer and bring up imperial decrees on my screen.

If the information was out there, why hasn't a work like yours been done before?

Well, people have been writing — not a biography like mine, but aspects of it. I mean, Chinese scholars have been doing various aspects of her rule and her time, and have done a lot of work. They didn't write a biography, but I have benefited from their discoveries and their work.

Is it sad for you that the book is not widely available in China at the moment?

Well, not just not widely available, I hope it's not going to be banned! I'm translating the book into Chinese and it's going to be published next year. I do hope it may be published in mainland China. But I don't know — we'll just have to see.

What are your plans after you're finished with this book tour?

My plan at the moment is to translate the book into Chinese. It's a lot of work — I've done half the work — and I just need perhaps more time to focus on the translation, which is what I'm going to do after I get back to London from the States.

But after that?

Haven't got any plans. No doubt, some time, somewhere, inspiration will come.

Shares