“A very great man will be visiting us,” Dad told me. “Someone who’s going to change our country.” A major figure in the African National Congress was coming to Londolozi. I expected someone dressed in a sharp suit, his eyes hidden behind designer sunglasses. Yet when I walked into Nelson Mandela’s bedroom with the breakfast tray, I found no stiff head of state but a warm, unaffected man.

Mandela sat up, and I put the tray next to him. He thanked me graciously and began chatting about the previous night’s game drive: “Oh, last night we had an amazing time. We saw a leopard. We saw it jump onto the back of a buck.”

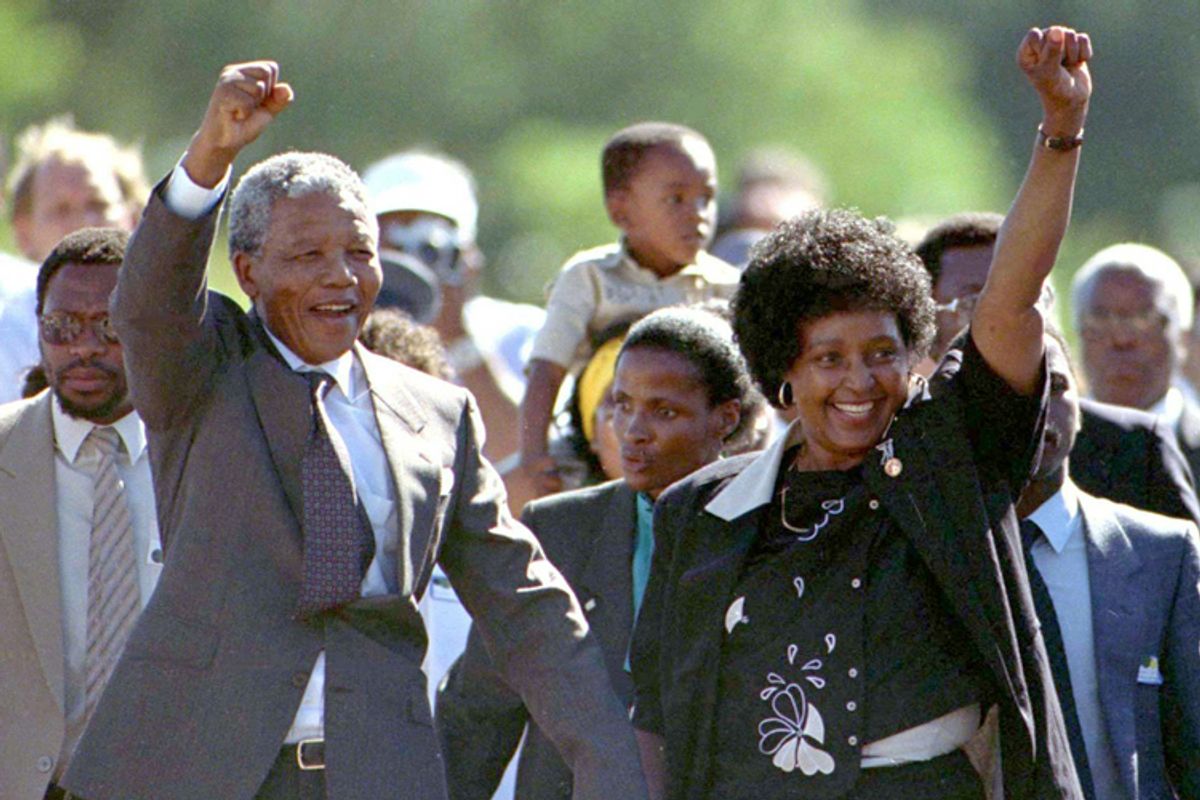

The man we all called Madiba (his family tribal name) radiated humility, walking the grounds in a beat-up boxer’s T-shirt, old tracksuit pants, and scuffed slippers. He was still trying to adjust to his immense stature after being released from twenty-seven years of isolation, most of it in a cramped coffin of a ten-by-ten cell on Robben Island. His innocence had been utterly destroyed by forces of which I was then blissfully ignorant, yet somehow during that unjust imprisonment, he had restored his own soul.

It was 1990. Mandela had become one of the most famous and inspiring people in the world, yet parts of him were still deeply imbedded in his years of prison life. People close to him within the ANC realized that he needed a period of adjustment and recovery. Enos Mabuza, an activist who had been close with my family for years, believed that Londoz, where apartheid’s tentacles had never reached, would be the perfect place for Mandela to relax. Most important, if the people wanted to put themselves in his path, they’d risk getting eaten—an unusually compelling deterrent.

Three months after his release from prison, Mandela paid the first of many visits to our reserve. At first he stayed in one of the guest chalets, but once he became more comfortable with the place, he preferred the quiet of our family cottage, where the accommodations were far more modest: a bed and a bookshelf. He liked the simplicity and being away from the hustle and bustle of the camp. He fell into a nice routine each morning: he would sleep in and then have a late breakfast with my uncle. Having already returned from an early morning’s filming, Uncle John would sit at the head of a large stinkwood table, pour his muesli, and cut a very ripe banana into it. In true JV style, Uncle John treated Mandela exactly the same as he treated everyone else: as an equal and a friend. I have no doubt that if Mandela had been out in the bush during an amazing action sequence, Uncle John would have made him a camera assistant. Nelson would sit to John’s left with a plate of fruit, and they would discuss recent events on the reserve, including the highlights of the morning’s footage and the animal sightings from Mandela’s latest game drive, which never failed to enchant him. I joined them often, although I can’t say that, at age seven, I fully appreciated what momentous occasions these were.

A few weeks into this routine, Mandela invited Uncle John to join him for a more official lunch at the camp with some ANC members who had come to the reserve to see him. Once again, I expected sharp suits, but these men were dressed in typical strugglewear: jeans and black leather jackets, more like union leaders than politicians. From the time they arrived on the front deck of the camp, it was clear that this was an event beyond the casual breakfast-in-slippers routine. When it came time to be seated, Uncle John, in a rare moment of tact, headed for a side seat at the table. Nelson stopped the proceedings. “No, John,” he said in his gracious way. “I would never take your place at the head. Please come and sit here.”

Whenever I went into the village with Mandela, it was clear just how important he was. People flocked around him, not in a mobbing way but at a respectful remove. Everyone just wanted to drink in his peaceful presence. Years later, when Oprah Winfrey asked him to be on her show, he agreed, then asked, “What will it be about?” He didn’t seem to comprehend that viewers would be on the edge of their seats, waiting to hear the story of a man unjustly imprisoned for twenty-seven years, who upon being freed immediately reconciled with his jailers and guided a reunited country toward freedom.

Madiba was at Londolozi at the start of the CODESA talks between the ANC and the National Party, of which F. W. de Klerk was the president. The country was fragile, and tensions were high; the talks between these deeply opposed parties were meant to be about how to communicate on equal footing in the future. Almost immediately, the right wing of the National Party drove an armored vehicle into the latest summits and took them over, waving their old South African flags, as inflammatory a gesture as raising a Confederate flag in post-Civil War America. Mandela asked Dad, Mom, and Uncle John to charter a helicopter to fly him to the scene immediately.

“We won’t do it,” they said. “If you land at the scene, they’ll shoot you.”

Mandela didn’t care. “I must be with my people. Charter me a helicopter.”

The argument grew quite heated. “We are your people,” Dad told him, “and it doesn’t help us if you fly off and get shot. We’ll charter you an airplane and fly you to a nearby airport and you can get a report before you go in.” Mandela stormed off. Shortly afterward, he returned and agreed with my parents and uncle. As it happened, by the time he flew in for the summit, the revolution was over and everyone was out having a barbecue.

This wasn’t the only time we saw Mandela assert himself on behalf of his people. One Saturday night, reports came in that ten people had been murdered in Alexandra Township, a poor black slum—more casualties of the Third Force, a group dedicated to the breakdown of negotiations between the ANC and the National Party. The Third Force was essentially made up of terrorists who committed atrocious acts and blamed them on one party or the other to try to blow apart the fragile peace.

We had an ancient TV in the family room with bunny ears antennae. The next morning as Dad and Mandela watched the news, they saw only a snowy transmission of this tragedy. Our phone lines were down for scheduled maintenance. In classic Londolozi style, Dad came to a last-minute rescue with a jerry-rigged radiophone.

“De Klerk!” Mandela screamed into the line, trying to get his point across through heavy static. “I’m warning you! If the Third Force doesn’t stop, I’ll pull out of the negotiations!” The connection was so terrible that the future president of the ANC and the current president of South Africa couldn’t hear each other. Dad was frantic: the whole future of our country rested on a fuzzy phone line. Luckily, Dad was able to get the phone working and persuade Mandela to speak into the transmitter instead of holding it to his ear, and he and de Klerk came to a resolution. In late 1993, Mandela and de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in negotiating a peaceful transition against the backdrop of imminent civil war. And in 1994, Nelson Mandela became the first democratically elected president of South Africa.

Mandela’s visits coincided with one of the worst droughts we’d had in a long time. The Sand River had almost run dry because of a dam upriver controlled by the Gazankulu districts, a big reservation system. The Nationalist government at the time offered no protection for the waterways. Some farmers set up their farms right on the river, siphoning water for their land, building dams wherever they pleased, with no legislation to protect other people who likewise needed this vital resource. There was corruption and tribal infighting, a general disconnect between government policy and what people needed. Dad flew to Gazankulu to plead our case.

“You’ve got to open the water for the people downstream,” Dad said.

“No, our people need the water,” the local puppets of the government replied.

Dad flew back and told Mandela about the dilemma. “When I’m in power, let’s talk and solve this problem,” Mandela promised. That very night there was a great downpour. All the staff members met in the village; everyone stood in a circle and offered thanks for the rain. Mandela gave a speech, saying that Londolozi was in line with his vision for the future of South Africa, a society of racial harmony.

Mandela proved true to his word; when he became president, he involved Dad in the drafting of the National Water Act, which mandated a more democratic handling of rivers. People could no longer deny others an essential resource by blocking it upstream.

It was Mom’s dream for Madiba to do the foreword for the book she’d been working on, I Speak of Africa: The Story of Londolozi Game Reserve. This book was deeply important to her. Filled with lush photographs from the reserve, it not only told the story of the lodge’s beginnings but described our family’s philosophy on conservation. Originally, not wanting to cash in on their relationship, she sent her request through his foundation, the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. Weeks dragged by as her message got bogged down in bureaucracy. Finally, my mother decided to throw caution to the wind. She phoned the security desk at the Union Buildings and cheerfully talked someone into giving her Madiba’s home number. Such was life in the new democracy. She called his house directly. “I’d like to speak to Madiba, please.”

The clearly flummoxed person on the other end of the line told her to hold on. Moments later Mandela came on. “Madiba, it’s Shanny from Londolozi speaking.”

“How wonderful to hear from you. How are you?”

“Oh, just fine. I wanted to ask you something.”

“Do you mind? I’m just in the middle of watching the news. Could I ask you to ring me back in ten minutes?”

When Mandela picked up the phone ten minutes later, it was with a warm “Now, my dear, how can I help you?”

“Oh, Madiba, this is a long shot, I’m sure you get asked to do this a million times, but would you consider writing the foreword for my book?”

“Yes, it would be my pleasure.”

Within twenty-four hours Mom and Dad had driven to Pretoria, to the office of the president. Madiba had put his thoughts down, and his letter was given the official seal from the president’s office. It appears as the foreword to I Speak of Africa, opposite a gorgeous rendering of Madiba with Dave, Shan, and John Varty. I was particularly moved by the final paragraphs:

During my long walk to freedom, I had the rare privilege to visit Londolozi. There I saw people of all races living in harmony amidst the beauty that Mother Nature offers. There I saw a living lion in the wild.

Londolozi represents a model of the dream I cherish for the future of nature preservation in our country.

After Mandela became president, Mom was staying at the Balalaika Hotel in Johannesburg when Mandela suddenly walked into the foyer surrounded by press and security. Spotting her, he broke from the crowd and walked across the lobby to greet her, holding her hand for an extended period of time in a typically African way as they chatted. My mother was blown away. Years later, when I was captaining a cricket team, she would remind me of Madiba’s example: “It’s the little things, Boyd, the little things that make the great leaders.”

Twenty years after the morning I met Madiba, in the room that is now mine, I realized all over again how extraordinary he was, and is. He’d woken up exactly as I am doing now, just a few pounds of bones and blood and gristle and tired muscle. He had to generate within himself the energy to extend the restoration of his country beyond that small human body. I couldn’t imagine how he must have felt, emerging from the terrible isolation of prison immediately into cheering crowds, a whole nation desperately in need of what he represented.

Mandela is revered by all for the way he catalyzed change in our country. His birthday will always be a major holiday at Londolozi, filled with singing, dancing, and eating. I join in the wild games of soccer played on a field where lions have been known to sit and watch. In the heat of competition, race becomes irrelevant, with players and fans of all colors cheering and embracing; cooks and bottle washers clink glasses with wealthy First World guests. A flood of children snitch dollops of icing from the cake that says, “Happy Birthday, Madiba!” The Londolozi Ladies Choir, made up of cooks, housekeepers, and other staffers, provides a rousing soundtrack.

Nelson Mandela is proof that one individual can change the world.

Excerpted from the book "CATHEDRAL OF THE WILD" by Boyd Varty, to be published March 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Boyd Varty. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House. All rights reserved.

Shares