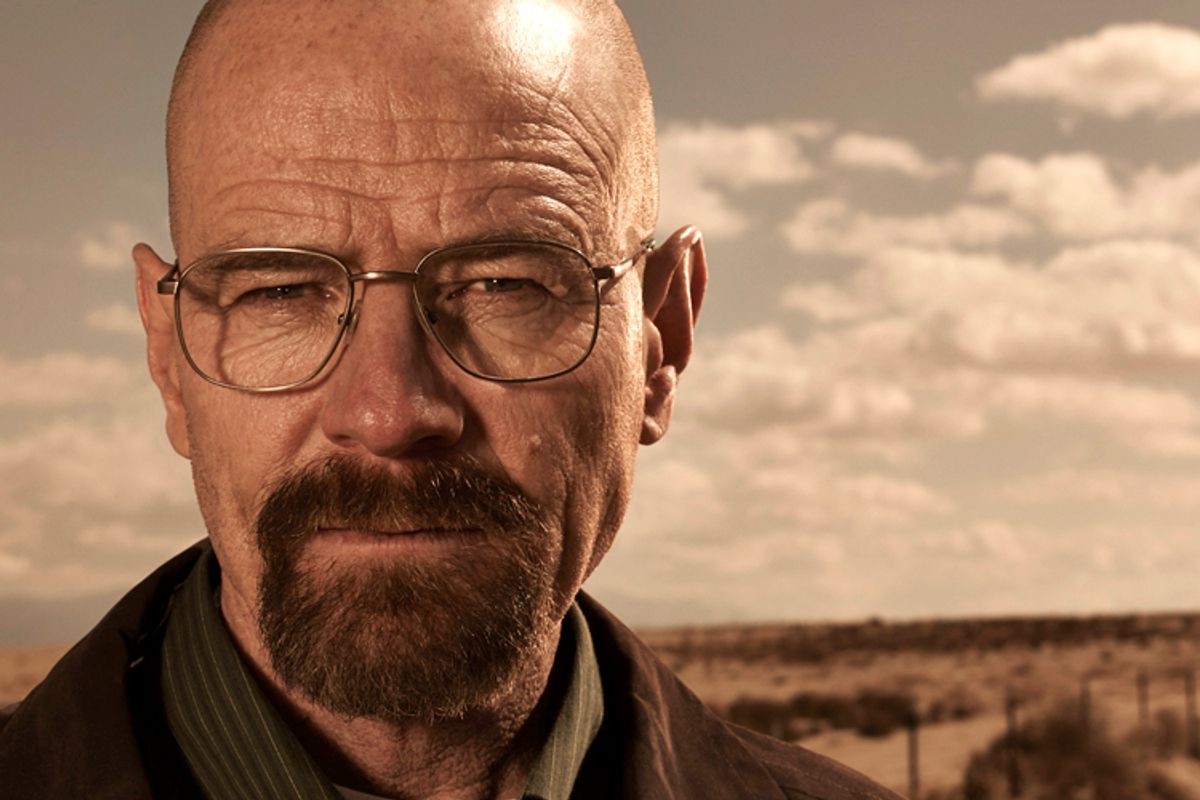

In the fictitious world of "Breaking Bad," Walter White produces methamphetamine in order to pay for his cancer treatment and leave his family financially secure after his death. In the real world, Dicky Joe Jackson decided to transport meth in order to pay for his son’s lifesaving medical treatment. White became a badass billionaire and indirect serial killer; Jackson became a “lifer,” sentenced to take his last breath behind bars so that his son could live.

Sadly, Jackson, who is 55 and has been in jail for 18 years, is only one of the 3,278 men and women serving a sentence of life in prison without parole, for nonviolent offenses. The fact that convicted murderers and rapists go free after serving only years or months in jail makes the cruel and draconian punishment for nonviolent crimes all the more absurd and perverse.

Calling me from the Forrest City Correctional Institution in eastern Arkansas, Jackson related many of the details of his heartbreaking story, the result of a combination of some of our nation’s greatest failures: an ineffective and destructive “war” on drugs, draconian sentencing and over-incarceration without even the pretense of rehabilitation, and a heartless healthcare system that forces people to make unthinkable choices.

Born and raised on a dairy farm in Boyd, Texas, Dicky Joe Jackson left high school after 10th grade to become a trucker, like his father. And like his father, and many truckers, he took speed to stay awake during long drives. In 1988, Jackson was convicted of possession of a half-gram of meth after a confidential informant posing as a fellow trucker at a Florida truck stop asked him for a pill. Then, in 1989, Jackson was convicted of transporting more than one kilogram of marijuana and served one year in a county jail in Tylertown, Miss. But far worse than his sentence was the news he received while still in jail: his 2-year-old son, Cole, had been diagnosed with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, an extremely rare autoimmune disease. Affecting one in 250,000 males, it causes recurrent bacterial, viral and fungal infections, lowers blood platelets and leads to easy bleeding and bruising.

Cole’s doctors explained that without a bone marrow transplant, he would likely have less than three years to live. The good news was that Cole’s 12-year-old sister, April, was a perfect match. The bad news was that the transplant would cost $250,000. And the Jackson family had recently lost their insurance coverage. They were given a choice, Dicky says: raise the money and pay for the only hope Cole had to live, or seek hospice care that would make Cole as comfortable as possible as he died.

Letting Cole die was not an option, and the Jacksons quickly got to work raising money. They sold their belongings, and they wrote to family and friends asking for donations. They even wrote to celebrities ranging from members of the band Alabama to football players to Ronald Reagan, all of whom donated memorabilia for the Jacksons to auction off. The Jacksons were able to raise $50,000 this way. Because of the rarity of Cole’s disease, they found no foundations prepared to help. After applying to national charities for ill children, some twice, and getting nowhere, they reapplied to the National Children's Cancer Society, and received $50,000. But they were still $150,000 short of the money required to pay for the transplant. In addition, Cole had to receive a literal lifetime of chemotherapy, and a monthly hemoglobin treatment before and after the transplant, which cost $3,700 and had to be paid upfront.

“I was desperate,” Jackson says. “I had to get the money. Before I had kids, I’d never known there was a love like that. Once you have kids the whole game changes. There ain’t nothing you wouldn’t do for them especially if they’re sick. When Cole was younger, it looked like we just beat him all the time, because he would bruise all over if you just squeezed him or picked him up. You’d barely touch him and he’d bruise and that would just break your heart ... It made a crazy person out of me. I’d never faced anything like that and I hope no one else has to. But I guess it happens to a lot of people.”

In this crazy state, Jackson was working full-time driving livestock between Texas and California. A local meth dealer who knew about Cole’s medical situation asked Jackson if he would transport the drug from California to Texas on his drives; he would get around $5,000 for this, five times the $1,000 he would make transporting the livestock and produce. Once a month, Jackson transported the meth with his cargo. After a year, in 1995, Jackson was arrested for selling half a pound of methamphetamine to an undercover officer. The prosecution offered Jackson a chance to lower his sentence, but he refused to testify against his co-defendants, explaining to me: “If I make a mistake I’m gonna pay for it myself.” Jackson was found guilty of conspiring to posses or possessing with intent to distribute. The judge found that he either conspired to possess, or possessed, with intent to distribute, 81.5 kilograms; 358 times the amount that was found on him. Jackson was sentenced to three life sentences along with three 10-year charges.

The judge who presided over Jackson’s case has been accused of abuse of power and harsh and unfair sentencing. Appointed by President Bush in 1990, Judge John H. McBryde received a rare public reprimand in 1995 for his “intemperate, abusive and intimidating treatment of lawyers, fellow judges and others,” which “detrimentally affected the effective administration of justice and the business of the courts.” He was barred from hearing any new cases for a year. (McBryde's assistant told Salon that McBryde does not comment on cases.)

Jackson was incredulous at his sentence: “I had no idea they could do what they said they would do. They raided my house, they never found anything. I thought it was a bluff. But they did what they said they’d do.”

Significantly, the man who prosecuted Jackson doesn’t think he was the ringleader either. Now a judge in the Criminal District Court of Dallas, Michael R. Snipes, wrote a letter in support of clemency for Jackson: “I saw no indication that Mr. Jackson was violent, that he was any sort of large scale narcotics trafficker, or that he committed his crimes for any reason other than to get money to care for his gravely ill child.”

Though he has no chance of parole, Jackson is an ideal prisoner. He’s received more than 20 certificates, enrolled in all the drug and alcohol abuse programs offered, and studied everything from business to cooking. He volunteers, helping counsel suicidal inmates. Ironically, Jackson says, “When these guys get hopeless, I sit with them and talk to them — and this is coming from a guy who has no hope. They’ll get out in two years and I’m doing life and I’m the one talking them down.”

Still, writing to the ACLU, Jackson calls prison “a bad dream that never ends” and “lots of nights in your prayers you ask to not wake up the next day.” He’s seen several assaults and killings, but the hardest part, he says, has been missing “my kids growing up, and not being there. And now my grandkids. All my time at home was spent building stuff for my kids. It’s pretty tough.”

Jackson doesn’t deny his mistakes. “I know that what I did was not right or legal, even in a life and death situation, as ours was,” he wrote on the November Coalition's website. But he sees the punishment as inappropriate: “I’m no angel,” he tells me. But, he wrote, “I have never harmed a soul." And, as he points out to me, "There are people in here doing less than me for contract killings and child molestation.” Jackson sees the toll it’s taken on his family as unfair: “I don’t think other people should pay for my mistakes even though it seems like my family has been paying for mine.”

Jackson’s legal appeals have been exhausted and a presidential clemency plea was recently denied. But Dicky Joe Jackson is optimistic now that the American Civil Liberties Union has launched a campaign against life sentences without parole for nonviolent offenses. Their report “A Living Death: Life Without Parole for Nonviolent Offenses,” details the racist and classist application of life sentencing and introduces seemingly countless tragic stories like Jackson’s. Because of their efforts, including a petition asking President Obama to review federal cases of sentencing without parole, Jackson told me, he has hope: "Because for the first 17 years, there was nothing … It seems like this year they’ve got their minds set on doing something … I’m really worked up about it. I’m excited about it. Because that’s what it takes to change things, for people to become aware.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Dicky Joe Jackson's age. He is 55.

Shares