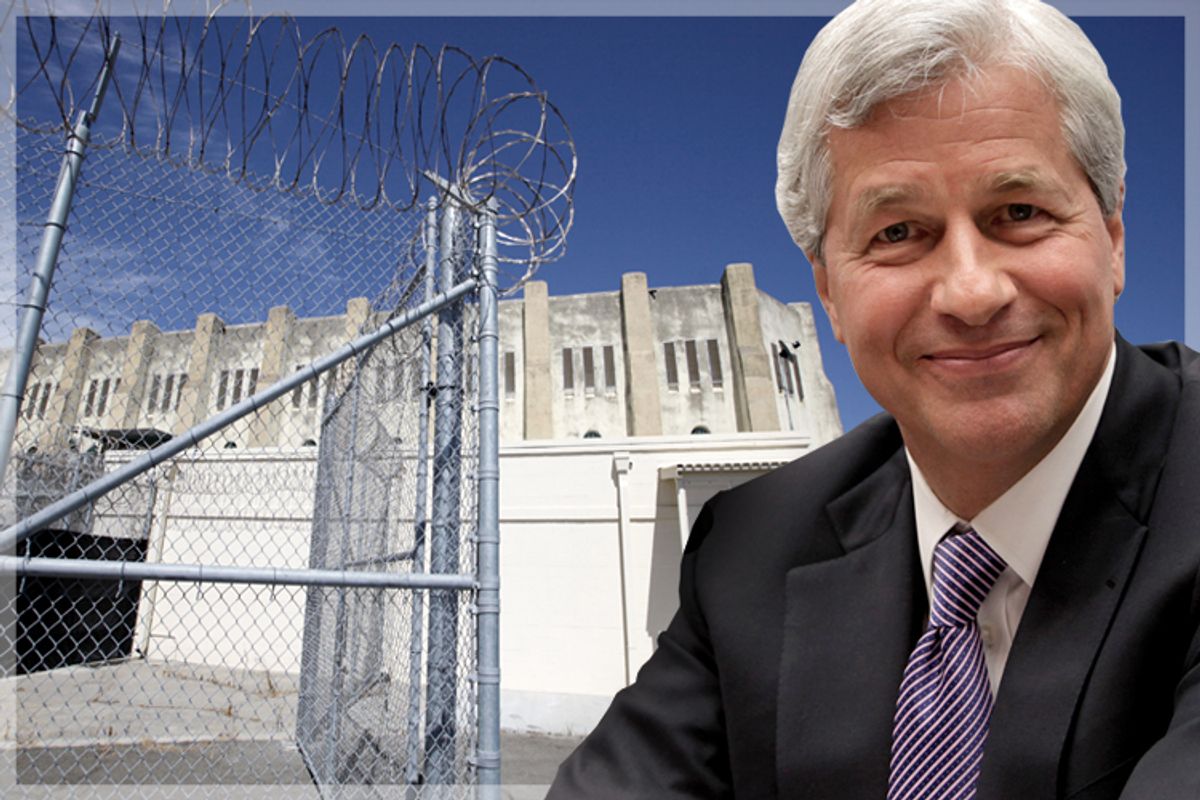

The crowd waited impatiently outside 270 Park Avenue, corporate headquarters of JPMorgan Chase. Photographers readied their cameras. Then, the murmuring grew into a low roar. There was CEO Jamie Dimon, accompanied by two FBI agents. His hands were tied behind his back, held together by handcuffs. As flashbulbs popped, the agents guided Dimon into an awaiting vehicle, and drove off to take him into police custody.

Christmas miracle? It doesn’t have to be. Even putting aside the rap sheet of crimes committed by JPMorgan Chase over the past several years for which its CEO can be said to be ultimately responsible, just a week ago, Jamie Dimon explicitly violated a federal statute that carries a prison sentence. That he’s a free man today, with no fear of prosecution, doesn’t only speak to our two-tiered system of justice in America. It should color our perceptions of new rules and regulations that supposedly “get tough” on the financial industry, as we recognize that any law is only as strong as the individuals who enforce them.

The law in question that Jamie Dimon violated, by his own admission, can be found in Section 906 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. In the aftermath of the 2001 financial crisis, when corporations like Enron and WorldCom melted down in accounting scandals, Congress passed and George W. Bush signed Sarbanes-Oxley, meant to reform corporate accounting and protect investors through additional disclosures.

Section 906 forces corporate CEOs and CFOs (chief financial officers) to add a written certification to every periodic financial statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. In this certification, the CEO and CFO must personally attest that the documents submitted to the SEC are accurate, as well as that the corporation has adequate internal controls. That phrase “internal controls” has a very specific meaning, covering the accuracy of all financial reporting, proper risk management, and compliance with all applicable regulations. Under Section 906, if the CEO or CFO knowingly or willfully make false certifications – i.e., if they know the SEC filing contains inaccurate information, or that the company’s internal controls are inadequate – they face fines of up to $5 million, and imprisonment of up to 20 years.

The idea here was to change corporate behavior by putting top executives personally on the hook for any wrongdoing. This would concentrate the minds of CEOs and CFOs, giving them a personal interest in ensuring regulatory and legal compliance. And it would assure investors that all accounting statements filed by the corporation were accurate, and all risks disclosed.

We know now that Wall Street firms like JPMorgan Chase routinely violated any number of laws leading up to and after the financial crisis. We know that the risks weren’t disclosed to investors in a timely manner, since multibillion-dollar settlements keep getting announced without warning. And we know enough to infer that the annual statements to the SEC that Jamie Dimon personally signed were inaccurate.

For example, the internal control group designed to manage risk inside the Chief Investment Office where the disastrous London Whale trades were placed only had one employee covering a large trading desk. Traders spent months covering up the massive losses in the trades, clearly displaying ineffective risk management and internal controls. Yet every year, Jamie Dimon signed a form saying the controls were adequate. In fact, in the settlement over the Whale trades, the bank admitted to both misstating financial results and lacking effective internal controls. This should have triggered Section 906. And that’s but one of a host of examples.

Perhaps you think this isn’t clear enough, that a jury would never convict Dimon on a Sarbanes-Oxley certification violation, because he couldn’t possibly have known at the time about the inadequate controls. First of all, the entire point of Section 906 is that Dimon and his fellow CEOs should not be able to wriggle off the hook with an “I know nothing” defense. But Dimon took this a step further just last week, providing prosecutors with what should be a smoking gun.

As Bloomberg’s Jonathan Weil noted, last week Dimon appeared at an investor conference put on by Goldman Sachs. And at this conference, he said, in public, “We have control issues we’ve got to fix. We’re taking an ax to it. We’re going to fix the problems that have been identified.”

Now, here’s Jamie Dimon’s most recent Sarbanes-Oxley certification, filed along with JPMorgan Chase’s quarterly report to the SEC (known as a 10-Q) on Nov. 1. In it, he attests to having personal knowledge of and responsibility for the internal controls of the bank, and he certified that they were effective. Yet just a month later, Dimon stated publicly that the control issues must be fixed. And remember, misstatements on Sarbanes-Oxley certifications carry criminal penalties of up to 20 years.

It’s impossible to believe that Jamie Dimon signs statements every quarter asserting that the internal controls at JPMorgan Chase are effective, only to be blindsided at some later point about their inadequacy. I’m sure that’s what his lawyers would try to claim in a criminal trial, but any marginally competent lawyer could blow such a defense out of the water. There’s only one reason why Jamie Dimon isn’t sitting in a jail cell today, and that’s because he holds the amulet of protection in America, namely a position of wealth and power.

This matters for more reasons than just Jamie Dimon’s personal comfort level. Just last week, regulators finalized the Volcker rule, designed to prevent banks from risky proprietary trading for their own profit. And one of the key measures touted by regulators is a CEO certification, where they have to state that their bank has “procedures to establish, maintain, enforce, review, test and modify” compliance with the Volcker rule. This is even weaker than the Sarbanes-Oxley certification, as they only have to certify that procedures are in place, not that those procedures are effective. And because Sarbanes-Oxley certification has been such a bust in holding corporate CEOs accountable, nobody should be hopeful that an even weaker provision in the Volcker rule will serve as anything more than window dressing.

As Judge Jed Rakoff recently wrote in a scathing essay in the New York Review of Books, the failure to prosecute those responsible for the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression “must be judged one of the more egregious failures of the criminal justice system in many years.” Law enforcement officials had the tools, from Sarbanes-Oxley on down, to hold the perpetrators to account. They failed, because they wanted to fail. They didn’t want to disrupt the financial industry by exposing its corruption.

And the predictable result is a lack of deterrent for a continuing series of crimes. Open the business pages at random and they often read like the police blotter. One day, it’s contractors of Bank of America scamming homeowners seeking loan modifications (in ways substantially similar to the scams I reported on this summer for Salon). The next, it’s JPMorgan Chase settling allegations that it failed to inform authorities about its banking client Bernie Madoff and his Ponzi scheme (the settlement reportedly includes a “deferred prosecution agreement,” where JPMorgan and the government agree that a crime has been committed but that nobody will actually be indicted for it).

In a way, this puts us back where we started. Madoff was frog-marched out of his New York City penthouse apartment, disgraced for defrauding investors out of their life savings. Madoff’s true error, apparently, was that he didn’t engage in this conduct while an executive at a Too Big to Fail bank. He would have then received that protected status conferred upon all top Wall Street executives.

Shares