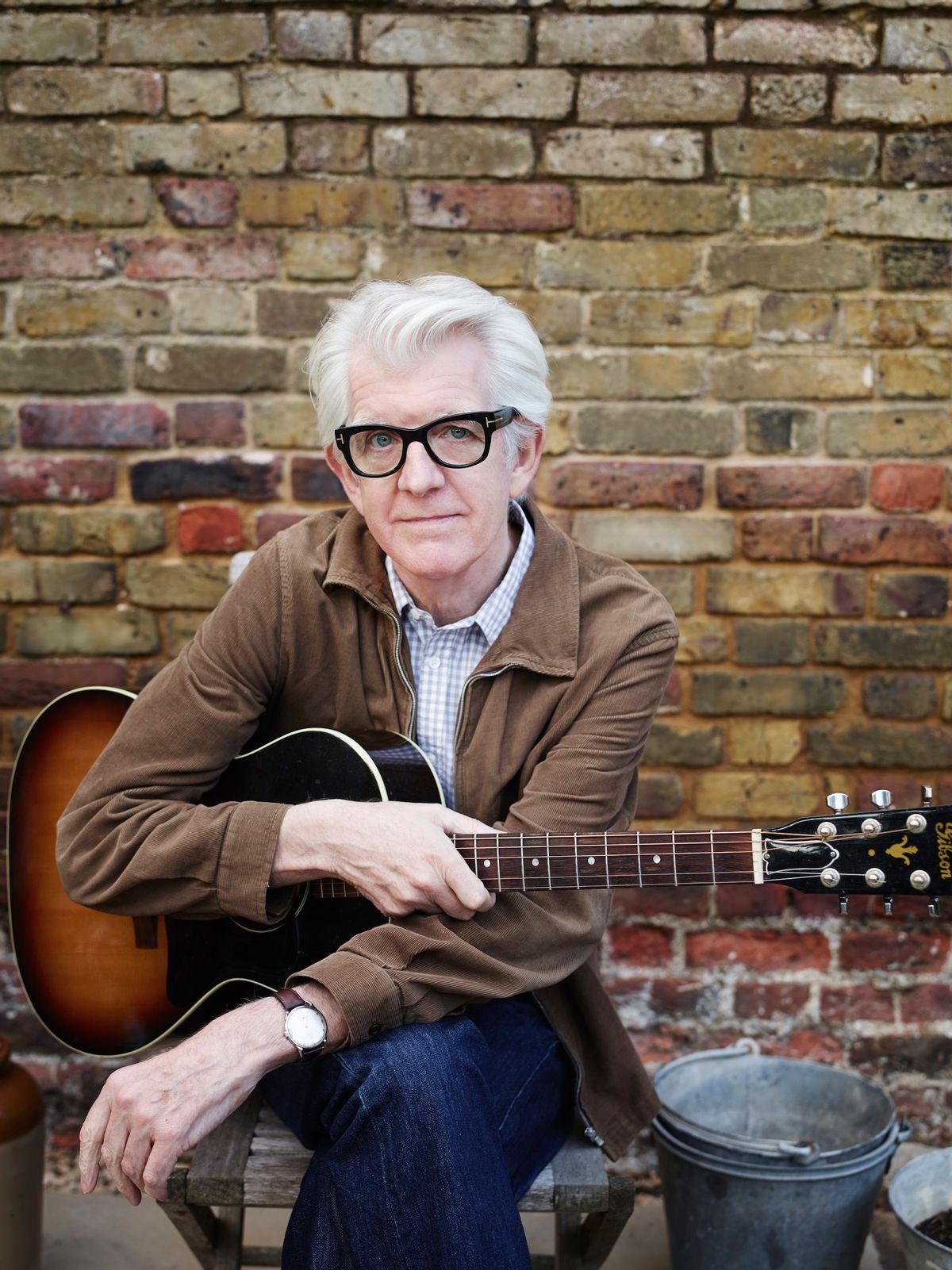

Nick Lowe helped pioneer pub rock and power-pop and punk rock, produced Elvis Costello and Graham Parker, the Damned and the Pretenders, was once Johnny Cash's son-in-law, and has written a handful of the most enduring songs of our time -- including "What's So Funny About Peace, Love and Understanding."

That song was made famous by Elvis Costello many years after Lowe recorded it with Brinsley Schwarz, and while it's been such a popular cover over the years that it seems to be owned by us all, the royalties still flow back to Lowe. And those royalties helped turn a midlife crisis into an artistic reinvention -- "Peace, Love and Understanding" was covered on "The Bodyguard" soundtrack, which also included an all-time smash hit in Whitney Houston's "I Will Always Love You." Lowe reaped millions.

The unexpected windfall allowed Lowe to reinvest in himself, 25 years into a long career, and remake himself as a thoughtful and wry romantic. He's on a remarkable run of albums, which started with 1994's "The Impossible Bird" but has paused momentarily for a holiday album, "Quality Street," a mix of traditional songs, lost songs unearthed with help from brand-name friends and a couple of seasonal originals.

We met earlier this month at his hotel in New York to talk holiday cheer and his brilliant career.

Why did you want to do a Christmas album? Holiday releases have gotten so much better in recent years, but for a long time they were the ultimate label-requested filler. And as a guy who has been so skeptical about “loving his label,” I would have imagined you holding on to suspicion of the concept.

You’re absolutely right.

And yet I’ve seen you talk about being such a fan of Christmas music that it enters heavy rotation in your house weeks before the holidays...

Yes, you’re right. The idea did come from my record company, and I was really negative and quite snooty about it, actually. I was quite surprised about that because, as you say, I like Christmas music. We play it in our house from the beginning of December to the new year, really. But I suppose what shocked me was this: I suddenly realized that I thought I was a bit too grand and artsy-fartsy to sully my hard-won reputation. And I was horrified to realize that. And then, I realized that it’s got something to do with the U.K., too. It’s very difficult to get anyone in the U.K. to listen to this record because they just don’t want to hear any chestnuts roasting on an open fire anymore.

That’s a song that’s been done and done well a long time ago. You’re not going to make that better.

Right. What I wanted to do was do a record which was good and imaginative, but wasn’t sort of hipper-than-thou and gets into the spirit of Christmas -- that was not cynical and was big-hearted and warm-spirited, but actually would take repeated listening, so that people could dig it out next year, and indeed the next one and the next one. But, as I say, even “my people” in the U.K., when I finished --

“I don’t know about this, Nick. He’s gone soft and off the rails now!”

Whenever I talked about it, they would have this expression on their face sort of like the one you’ve got when you speak to a slightly elderly and confused neighbor. Sort of pitying but encouraging, with slanty eyebrows -- that kind of look. So, as I say, that’s why I reacted in the way I did -- because I too have gotten beaten down over the years by “Jingle Bells” and the same 12 songs that everyone does. It’s unimaginative and uninspiring. If I want to hear chestnuts roasting over an open fire, I’ll listen to Mel Tormé, who wrote it, or Nat King Cole. I don’t really want to hear Leona Lewis or someone like that.

So how do you go about putting this together with those thoughts in mind, but also as sort of a historian of those songs. How do you stand up to your own bar of “I can make a record of Christmas songs that would be valuable and stand the test of time”?

You’re right -- the problem was never going to be recording. It was always going to be finding the material. I’m fortunate in that -- not that I’ve got lots of records, but that I’ve got lots of friends who’ve got lots of records. So I put the word out and said, “I’m going to do this -- give me a hand here.” Ry Cooder, Ron Sexsmith. So they came by every post, so to speak.

Like three wise men bearing gifts.

Yes, indeed. There were scads of them, mainly from the United States. A lot of them are great records. But, as we all know, a great record isn’t necessarily a great song. What I wanted to do was try to find songs that I felt I could actually put across and get into, rather than just doing “Oh, that’s funny -- let’s do that one” and knocking it out. I wanted it to actually sound as if I’d gotten into it. That was hard. But, it made me write some things, which I didn’t think I was going to have to at all. It is a bit of a tall order.

You’re in the middle of a remarkable run of albums about aging, about fatherhood, about men in relationships -- did you think at all, “I don’t know if I want to interrupt that by going and doing a holiday thing.”

I’m really sort of past that career-thinking. I don’t really feel the drive anymore of,“Let me get my point across!” I feel much more relaxed about the whole thing. I do feel like a hack, really, and especially now with record sales -- as we know, nobody buys records anymore. And so much of it is just a very, very bad time. People don’t want songs.

People want songs. They just don’t want to pay for any of the songs.

Yes, but also other artists -- they’re not really on the lookout so much as they were, or they’re really honing up their own skills. So you’ve got to get it where you can. But I did this Christmas thing and no, I didn’t feel -- well, that was part of my initial reaction, which lasted for about an hour, I suppose, until I came to my senses. I didn’t feel at all like I was interfering with some fantastic train of thought. We had a ball.

You called yourself a hack. That’s an interesting word that doesn’t always have positive associations. Why a hack?

Well, I think it’s quite an honorable tradition, and here we are sitting a few steps from the Brill Building, which is -- I don’t know what it was like, it was before my time -- but I was an avid consumer of the stuff they used to do there, and down the road a little bit, where they did all the R&B stuff. I had a romantic idea of what that was like.

Anyway, I feel I’m sort of a modern-day equivalent, although I sometimes think that songwriting now -- I did say nobody’s buying records, nobody’s looking for songs -- is sort of a craft which is dying out. I feel a bit like someone who makes thatched roofs or dry stone walls -- they’re sort of country crafts, what people go, “Oh that looks nice! Marvelous! They don’t do that anymore."

What do you think happened?

I mean, that is ridiculous, because the youngsters still hear songs and say, “Oh, it’s a great tune.” But it’s that way with people from my era -- it’s just a generational thing, so I’m not seething with rage over this.

There’s such a groove and a swing to your music -- American music was so influential for you, but especially American black music. How did you find that music in ’60s England?

We’re the last of the swing generation; kids just don’t like swing. But to me, that’s what I always loved about the music I love. I listened to exclusively American music as a kid, even though I loved some of the British interpreters of American music -- people like Lonnie Donegan, who they always talk about as the Skiffle Guy -- because I think what I do is a skiffle, former British rockabilly, really. But I didn’t know, when I was 8 years old listening to Lonnie Donegan songs, that he was teaching me about Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy and all that stuff. But when I got older -- and my dad was in the RAF, so I used to hear a lot of forces’, American forces’, really, radio -- the BBC was quite stilted. But on American forces’ radio, you heard really good stuff -- and it was all swing. The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, they swung very, very hard. I always loved that stuff. And, again, when I got older and I started more -- well, in my teenage years I wouldn’t entertain my parents at all. We had plenty of our own music and parents had no place in it, unlike now when kids and parents like the same music.

Of course, now I openly embrace the music that my folks listened to, and they had very good taste as well. But it all swung -- that was the major, major part of it. And music that doesn’t -- I know it’s good, there’s plenty of music that doesn’t swing that’s good -- but I’m not interested in it. To me, the swing part, the roll of rock 'n’ roll, which I know has gone away -- it’s a cliché that rock has died, but rock 'n’ roll is interesting. And so it’s very flattering to me that you’ve asked that question.

So you finally get a band going in the late ’60s, and it’s post-British Invasion, and you were afraid that everything was over and you had missed it.

I did, although I thought it was still going on. Because it was just before the Beatles released “The White Album,” and the Stones were going strong. But yeah, I did sort of think it was over, but only because I was so low down on the totem pole, and in those days, unlike today, where if you’ve got a lick and a riff and you look cute, you go right to the top -- you’re picked out, there’s almost no way you can’t at least get a break -- but back then, you sort of had to take your chance. And, again, I think we were lucky, because it meant we could learn our craft in these shitty little clubs in Germany.

So you did those long residencies in Germany just like the Beatles did?

You play from 8 in the evening until 2 or 3 in the morning, and on the weekends you’d play from lunchtime until 2 or 3 in the morning -- but we were 18. There were girls and it was brilliant. I was straight out of boarding school; I thought I’d gone to heaven.

In those days bands played two 45-minute spots, that’s how it was -- the opening act -- generally us -- would go on, then the big band would do their 45, then us, then the big band would do their 45 again. So we had an hour-and-a-half, maybe two-hour repertoire, and when you do those German things, two hours isn’t going to last you. So you’ve got to learn tons and tons of things. Were we writing songs? No, we really weren’t there yet -- all covers, nearly everyone did. But we were trying to start writing our own songs. But we had a repertoire of hundreds of soul and pop songs.

And learning that many songs over that many genres must make you a better craftsman, a stronger and sturdier songwriter.

I didn’t think it would at the time -- I wanted to be on TV. I didn’t want to be in some freezing-cold van going up autobahns in Germany, but on reflection, I think I was really dead lucky.

That’s followed by Brinsley Schwarz, and helping start Stiff Records, and the common denominator of Elvis Costello. Were you simply going through demos in the office one day and there’s his tape?

No, he’d actually brought his tape into the office, and I ran into him on the Tube. But I knew him before that because he used to come see Brinsley Schwarz and we’d see him at our gigs when we played in the northwest of the U.K. And we actually played at the Cavern Club in Liverpool, and we were having a drink in the bar across the road and he walked in. He tells the story differently from me, but that is when we first spoke to each other. That is also the reason why, when I became his record producer, later on, he actually said, “I want to record ‘Peace, Love, and Understanding,’” because otherwise it would’ve been lost.

What did you hear on that demo tape that was so striking?

Well, I don’t know whether I thought it was very good when I first heard it. There were too many words, too many ideas in the song.

He had the right influences but it was too many chords, too many words. And the original idea was to sign him as a writer because he’s obviously so prolific. They were going to sign him as a writer and then Jake Riviera listened to the tape a few more times and said, “We’re nuts. This guy is really something else.”

And the job of turning him into something else falls to you!

Right, so I had the job of producing him, and I was a bit -- I knew him and I liked him -- he was sort of, how can I say it? Well, I still feel it, really. He was a bit like a little brother. It was kind of an annoying job. “He writes too many words, and all those chords -- I’m a three-chord kind of guy.” Jake said, “Exactly! Turn him into a three-chord-guy. Try to prune him down.” I sort of did alright, trying to do that on the first one.

And you embark on a six-album run that’s as remarkable as any ever. And it doesn’t take long before he’s much more than a three-chord guy again!

It really sounds like I’m sort of blowing my own trumpet, but it really didn’t take too long for me to realize that I had to change my act and be much more acquiescent to what he wanted. Sometimes he’d say, “I think we should do this here,” and I’d say, “Oh no no no, listen kid -- just leave all that stuff to me, don’t bother your pretty little head about that.” But it didn’t take me long to realize that he actually had a real feel for stuff and the two of us could really come up with something. But in order for it to be the two of us, he had to be the dominant partner instead of me being the dominant partner, and I had to enable him to do it and to encourage him to do it, and then we could come up with something really, really good. It was a great lesson for me also in what stuff I took away from it. I can’t really remember what I used to do on those records. I just remember we used to turn up -- and also he had a great band, too. It’s not like they didn’t have anything to say, I can tell you that much.

But there’s no doubt that occasionally, when I hear some of those records come on the radio, I think, “Man, that’s really, really great stuff.”

And how did you end up working on the Damned albums. You were not a big punk rock fan at all.

Well, rather similar to EC. I’d met them. The punk scene really came out of the pub rock scene, an underground -- it only really worked in London; they tried to make it work in other cities but it didn’t really work. In London it was really big. It even became a term of derision, and I might’ve even used it myself -- that pub rock, it means this kind of turgid, blokesy music that only guys like.

But the initial pub rock was fabulous. It was a really great, sexy, fantastic, fun thing. And then punk thing certainly came out of that. The punk thing started in New York, there’s no doubt about that, but it was a much more arty thing here in New York, whereas in the U.K. it was way more sort of “yobby” and complainy. It was playground violence, really -- all that stupid spitting and all of that. It was all a pose.

Some people look at punk as the cleansing mechanism that smashed classic rock and the prog-rock bloat, but you’ve never seen it that way.

No, I never really liked -- well, what I liked about it was the mischief that it caused. I was a bit too old for that. I was 26 -- the Damned called me grandad. I thought they were great. I never liked punk music, but I love real punk music, like garage rock 'n' roll. My idea of punk is Iggy and the Stooges.

Again, they’re from Detroit and you feel the full legacy of that city’s music, white and black, in what the Stooges were doing.

Absolutely right, and not from some bunch from a council of state in south London -- that didn’t seem to me to be very interesting. But the Damned, who didn’t know very much about R&B, they knew about Iggy Pop and those people and the old Stones records and all of that, so to me they were like a garage rock 'n' roll band and I thought they were really great. I didn’t have any trouble hanging around with those guys.

But the mischief that was caused -- most of the people I’d really worked with was Elvis or the Pretenders -- who were really good musicians, but they had that attitude of “there’s things we’ve got to change.” We don’t want this dreary rock, these dreary singer-songwriters. My interest was in sweeping away some of the people in charge, some of the people in the record companies -- I had no animosity toward the musicians or the bands. We were all trying to make a living.

How did you see your job as producer, working with songs that were that good and artists who were that forceful?

Back then, if you said you were a producer loudly enough, people believed you. You didn't have to know how to, you know, actually work the equipment. I wasn't always right. But I was full of myself, and the more people said how I good I was, the more I believed it.

It was just an exciting time. The people who were in charge -- that’s whose heads I wanted to see roll, and indeed they did. That was very gratifying. We were doing something that the people in their ivory towers, as I saw it, could not control. The other reason was when Stiff started it was because there weren’t that many pubs and clubs in London then, where we used to congregate. The NME, which was the big paper that came out weekly, had a massive circulation -- like 750-800,000 copies a week -- and the journalists, the hip ones, knew what we were up to. We used to meet them at pubs and we could get a story in the paper that week. They knew they didn’t have to go through the publicity departments; it would take months to set up the interviews, and we could give them the scoop right then and there. We had a direct mouthpiece to our public. The big record companies couldn’t cope with that, so it was a perfect storm.

And then it’s only after all this, after being in bands and producing, that you get your first hit, “Cruel to be Kind,” which still leaps out of the speakers today.

It’s really, really handy, yeah, because it’s gives you a sort of validation. If you’ve actually got a bona fide hit 45 record, you can get away with anything. Attention from girls who wouldn't normally look twice. Getting tables in restaurants! It was a crazy time.

I’m always interested in the relationship musicians have to songs that take on lives of their own, that sometimes must be the most wonderful thing to have and to be able to pull out, and other times must have the draws of “ugh, I’ve got to do that one again.” I imagine a hit like that -- you feel different ways toward it over the years.

Yes, I know what you mean. I think I felt that sort albatrossy feeling you’re describing more at the time it was a hit much more than now. I love that song now. I really like playing it. I’m always quite surprised whenever I hear the record played on the radio, because it still gets played on the radio, but I’m always quite surprised. It’s a great little tune.

You enjoyed the success -- but it also seems like you were savvy enough about the business side of things to know that it would not last forever.

Yeah, I think you’re crediting me with more insight than I truly had. About that time I was -- it almost seemed like it was my time. That’s what I felt like. I’d done my time in Germany, and it was almost as if a voice said, “Kid, it’s your turn.” It seemed like everything I did either worked or it didn’t -- and if it didn’t, it didn’t matter. It was a really strange time, slightly out of control. I made a lot of mistakes then, but if I did I was like, “on to the next.” Some worked and some didn’t, until the time came when I became aware - -and I probably became aware earlier than had I not been a record producer, had one foot with the management -- I wasn’t just an artiste. They’re sometimes the last ones to know that their time is up. I knew that my time as a pop star, being on the covers of magazines, was over -- people were tiring of my schtick. I was tired of my schtick. I felt uninspired and uninspiring, and I needed to either get out of the business or do some serious, serious thinking.

That’s a brutal moment of self awareness.

It was. I was in a bad way. My marriage hadn’t been broken up but just sort of disappeared. We still really liked each other, we still do -- but she was touring and we just -- I was drinking and just -- uninspired is the best way I can explain it. I had gone to the well too many times. So I took stock, and I sort of laid down in a darkened room for a year, metaphorically speaking, and I thought to myself, “Well, I’ve done pretty well. If that’s it, I’ve done pretty well. I’ve written some hits, produced some good stuff for people. But why is it that I feel that I haven’t really started yet?” Almost as if I’d ticked a box -- hit record? Tick. Produced, recorded? Tick. Stiff Records -- there at the beginning. Tick. But at that time, unlike now where you can’t move without hitting people doing good work in their 60s and 70s --

There were almost no examples of that then.

There were people who’d been around for a long time --

But they weren’t doing new work. Nobody was aching for the new Chuck Berry song. That wasn’t why you went to see him.

Right, no one was waiting for the new Chuck Berry record, as great as his influence is, but you wouldn’t really go and see him to hear something new. And I thought, well, it’s not like that in blues, jazz, or even country western. But not in pop. Frank Sinatra was in his 50s, but -- I thought, I’m going to see if I can sort of reinvent myself, because inevitably I’m going to get old in this business, and the last thing I want to do is to jump around like I was in a rock band. That would be my idea of hell. To let people relive their youth through me. And a lot of my contemporaries have had to do that. But I really made up my mind that that was not what I was going to do.

Obviously I was going to get older, but I was going to figure out a way of embracing that. I thought, if I can get it right, younger people will dig it. I won’t just be preaching to an older crowd. I thought I could find a new audience, but I thought it would take some time, and a lot of people -- old fans -- would fall away. Because it wouldn’t be the same thing. I had to make things work on acoustic guitar, make my records sound like demos, and really sell the songs.

That’s a big investment in time. But with an assist from Whitney Houston….

Then I had this extraordinary thing happen. Yeah, thanks to "The Bodyguard" I made this -- I also made a decent record, which in my view was the first one I’d done for a while. I was trying to figure out a new way of recording myself and writing for myself. But I couldn’t really get anyone to sort of understand what I wrote about on "Pinker and Prouder Than Previous"; I would doubt myself, whether I had something or not. I made a few records where I was trying to get to it, but it was all a bit -- not half-hearted, but it wasn’t working. I don’t know, I haven’t listened to those records for a long time now.

Anyway, I was trying to get to a place a little higher. But it was almost like starting out in Germany, because my currency was so low at the time that I could sort of work away and do stuff without anyone noticing. No one really noticed, because my thing was way down -- my career was sort of on the floor really. Then, suddenly, I came up with this really good record. It coincided with me making a lot of money from “The Bodyguard.”

You must’ve not even believed that. “I Will Always Love You” becomes one of the biggest songs of all time -- and "Peace Love and Understanding" gets covered on the soundtrack, so you get royalties on every album.

It sold an unbelievable amount of records -- 120 million copies or something. Of course, my payday was pennies comparatively.

Pennies on 120 million records, you’re talking real money.

Yes -- a lot of money. Most importantly, I was able to tour the United States, where my audience was and still is, and let them know that I had this. We could travel in a decent bus and stay in a reasonable hotel, and then I could make another one. That just about took care of the money I made from “The Bodyguard,” but once I did that it caught fire, and I was sort of off again. But it wasn’t overnight. It took about two or three more albums, and slowly, slowly, slowly, now I’m lucky enough to be enjoying this sort of second career. I can’t believe my luck.

Why do you think that is? It’s an interesting time because you do now have people performing and being really creatively vital into their 50s, 60s, 70s in rock.

Yes, it really is. It’s trickiest, as you say, to wear your experience, your longevity, lightly, so it gives you some credibility when you’re not shoving it in people’s faces. Look at me, I’m a heritage guy -- I’ve been around for ages. Like you said, if you keep working and keep doing things -- especially in my case, with younger people, which I’m really interested in --

And Elvis Costello does that. “I’ll make an album with the Roots,” or this is my classical year, I’m going to tour with an orchestra.”

I can’t compare myself to his unbelievable work rate or else I’ll have to stay in bed and die. I can’t do that comparison. But I think it’s also got to do with, compared to my generation, young people are much less snobby about music than my generation. We didn’t want anything to do with our parents’ music; we said, “this is good, this is bad.”

Last question: Tell me about where the phrase “pure pop for now people” came from. Royalties on that would probably rival Elvis’ for “dancing about architecture” or the line about how everyone who heard the Velvet Underground started a band...

I think at the time, to blatantly say you were pop -- I think when I made that album -- nobody wanted to admit they were pop. Even pop people didn’t want to say they were pop. So to actually openly embrace it, to say “what I do is pure pop,” it was sort of retro, but it was kind of a rallying call. But yes, who would’ve dreamt that it would have caught on?

Shares