"Creative writing is dying, if not dead," moaned one commenter, and he wasn't alone. The story that provoked this particular episode of hand-wringing appeared in the New York Times' Bits blog, and had to do with the ability of new e-book subscription services like Oyster and Scribd to track their members' reading habits. If authors are armed with data about, for example, whether readers finish a book -- and the exact point at which they abandon it if they don't -- then, wrote David Streitfeld, they "can shape their books to please their readers more."

E-book retailers like Amazon and Barnes & Noble have been collecting information like this for a while now, but they keep it to themselves. Oyster and Scribd -- no doubt aware that these days there's much more money to be made from people's fantasies of becoming successful authors than there is from actually selling books to readers -- have said they are willing to share the data they gather, presumably for a fee. And authors, especially self-published authors, are very interested. Quinn Loftis, a self-published author of YA fiction who reportedly makes a "six-figure annual income" from her books, told Streitfeld, "If you write as a business, you have to sell books. To do that, you have to cater to the market. I don’t want to write a novel because I want to write it. I want to write it because people will enjoy it."

That's the sort of statement that inevitably cues a chorus of laments about the decline of Western Civilization in general and literature in particular. Not to mention the predictable dumb jokes about how it's a good thing that some past great (Shakespeare or Joyce usually) isn't around to see their work degraded by such fads.

The truth is that tailoring books to reader preferences has been going on for decades, and the Internet is only making this process more efficient. That doesn't mean that, in the future, literary novelists like Donna Tartt or James McBride are going to be expected to market-research their books like a Hollywood filmmaker forced to submit his would-be blockbuster to the scrutiny of a test audience. While the editors who work with such writers are not above suggesting a sunnier ending or more intelligible plot points every now and then, for the most part, authors like these are signed on because of the originality of the work they produce. Only Donna Tartt can write a Donna Tartt novel, and it would take a very foolish editor to interfere overmuch with her process.

But a sizable sector of publishing doesn't put a premium on originality, and not coincidentally, this is the same part of the book market that has been most transformed by the e-book self-publishing explosion. In genres like young adult fiction, romance, urban fantasy, thrillers, mysteries, spy novels and various fusions thereof, many readers prefer the familiar and the formulaic.

Romance publishing in particular has long made a science of creating pleasant, disposable fiction for readers seeking an escape from everyday life. Categories and lines of books were designed to look alike, despite having myriad authors, and aspiring romance writers were given outlines and lists of requirements native to particular subgenres (the heroine must be a virgin, the hero must be a duke, etc.). But romance isn't the only form of popular fiction in which authors crank out made-to-order work; a friend of mine who wrote an interesting mystery set in a nursing home was recently sent a list of desired cozy-mystery genres by a publisher who thought she might be able to supply them with whodunits set among communities of scrapbook makers, pastry chefs and quilters.

In the past, publishers of mass-market paperback fiction had to deduce what their repeat customers expected from, say, a series about a kick-ass exorcist in leather pants and her adventures in the greater St. Louis area or a former Navy SEAL turned private eye solving crimes in San Diego. They and their authors got feedback from readers, librarians and booksellers about what went over well and what didn't, but there was no systematic way to assemble and evaluate that feedback. There is an art (well, maybe a craft) to successful genre publishing, and much of it has been rooted in the intuition of editors and publishers about what readers want.

New e-book subscription services like Oyster and Scribd, with their limited inventory of top-shelf titles, are well-suited to such readers. You can't get "The Goldfinch" or Eleanor Catton's "The Luminaries" from Oyster, but you can gorge on a seemingly infinite array of erotic romances patterned after "50 Shades of Grey," many of them self-published by writers who are eager both to know what readers want and to give it to them. But whether learning that most readers bail out halfway through their third chapter can help them much is uncertain. As Streitfeld pointed out, "Pride and Prejudice," an incontestably popular novel, is finished by less than 1 percent of the Oyster subscribers who open it, but why? Possibly many of them simply chose it as a sample text when experimenting with the app's features, while others, having already read the novel multiple times, really just popped in to revisit a favorite passage.

Writers who want constructive feedback from readers have better options. Many self-published authors use "beta readers" while revising their early drafts, a practice also common in fan fiction communities. Others post portions of their works-in-progress to blogs and gauge the response from their fans. With finished books, there are reader reviews on Amazon and social networking sites like Goodreads and Booklikes that can provide far more detailed reactions, even if the opinions aren't necessarily representative or especially articulate.

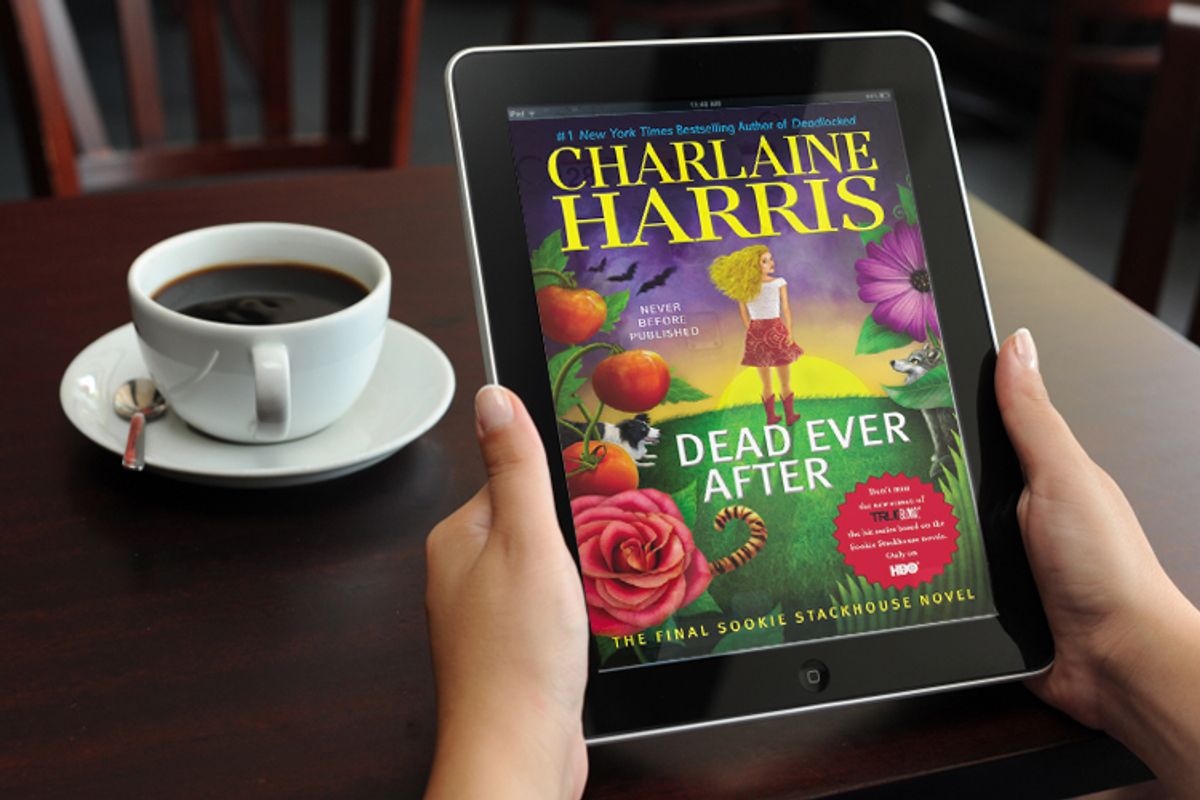

Not coincidentally, the most collaborative (and contentious) reader-author interactions happen in the online communities that have grown up around the genres where formula flourishes. The world of young adult fantasy and romance fiction is one where the line between readers and authors can get pretty blurry. Readers, who often take credit for a favorite author's success, feel entitled to complain loudly if they don't like where a story is going, or where it ends. Fans of Charlaine Harris' bestselling Sookie Stackhouse series vented their outrage all over the Internet when Harris gave her heroine a fate that was not to their liking. Threats were made, both personal and economic. "I won't be investing anymore time or money in works by this author," one reader wrote on Amazon. "We read fantasy for an escape, not disappointment." Of course, she had to finish the book to arrive at that opinion, so within Oyster's limited metrics, she might even register as a happy customer.

But no matter, because she wouldn't have changed Harris' mind in either case. As Harris' agent told the Guardian, the author expected a certain faction of her fans to be deeply displeased with the conclusion of Sookie's story and decided not to go on book tour to avoid being confronted by them. Still, she stuck to her guns. "I'm confident I stayed true to the characters I'd been writing for so many years," the beleaguered author wrote on her Facebook page. If she can hold out, I'm pretty sure Shakespeare and James Joyce would have managed it, too.

Further reading

Disgruntled fans threaten Charlaine Harris over conclusion to Sookie Stackhouse series

Shares