With one relatively insignificant clause buried on Page 364 of a massive budget bill that will get voted on today, Congress told us everything we need to know about federal spending priorities, the empty rhetoric of “budget discipline” and the power of the military-industrial complex. We learned that Congress can't fund anything -- like food stamps or unemployment insurance -- without a spending cut to offset it ... unless the item in question has something to do with the military.

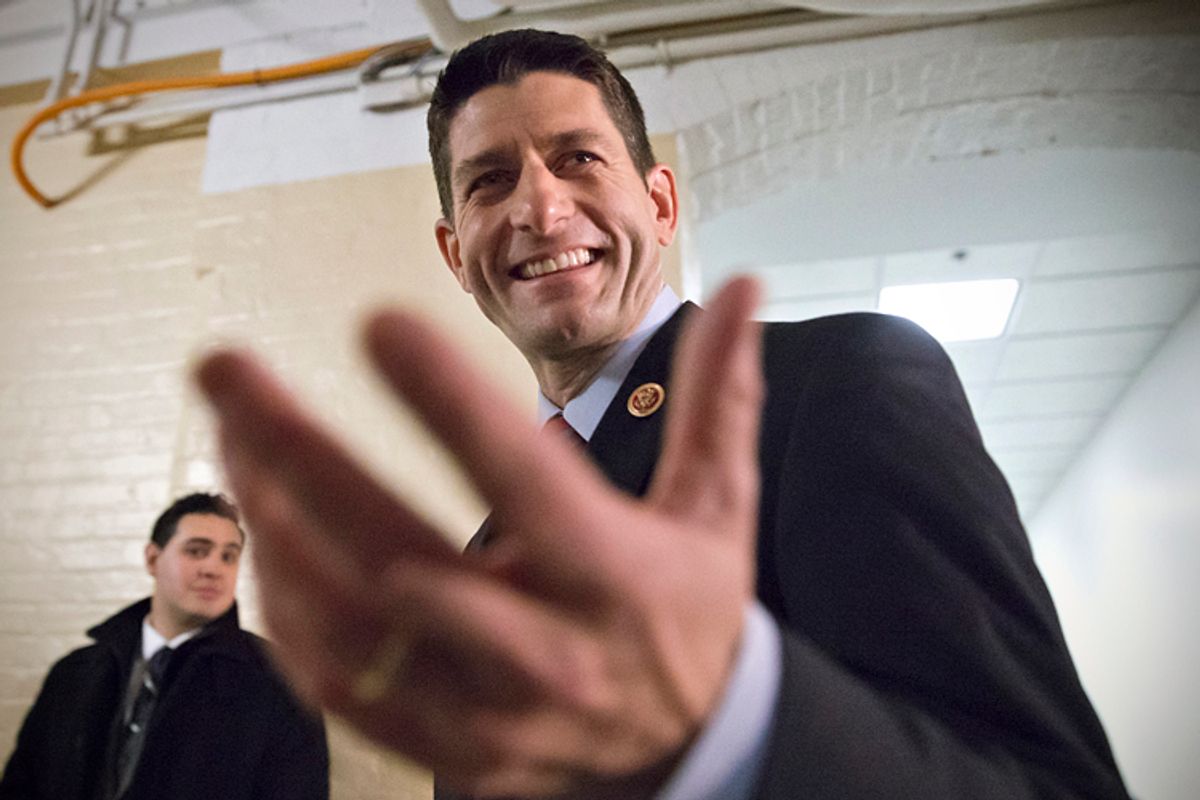

Let’s back up. Last month, Paul Ryan and Patty Murray reached a budget agreement that reversed some of the insidious sequestration cuts that have been whacking the economy for the past year. But each restoration of those cuts, we were told, had to be “paid for” by some alternative cut to the budget over the long term.

Among the various offsets chosen by Ryan and Murray were higher pension contributions for federal employees. Initially those contributions were scheduled to offset $12 billion in sequestration cuts, but in a move both lawmakers explicitly described as one of basic equity, $6 billion was spared, with the savings instead achieved by reducing annual cost of living increases to military pensions for veterans who retire with 20 years or more of service and are under age 62. “We also think it’s important that military families as well as non-military families are treated fairly,” Ryan said at a press conference announcing the deal, and he subsequently defended the cuts in an Op-Ed.

Predictably, service member organizations and their champions in Washington decried the cuts, and immediately agitated for a rollback. Career military who signed up for service believing they would get one benefit upon retirement, only to get a lesser one, were treated wrongly, these advocates said (and they’re right). However, pretty much nobody came to the aid of non-military federal employees, though the hit to their pensions was exactly the same in scope. And nary a soul bothered to mention that top officers like admirals and generals got to keep their generous pensions without any rollback, despite benefits as high as $273,000 a year.

The budget deal authorized a baseline level of spending, but did not appropriate specific dollar amounts to federal agencies. So House and Senate negotiators on the respective Appropriations Committees did that work, and yesterday reached a deal on an “omnibus” bill to fund all facets of the government for the rest of the fiscal year.

Which brings us to Page 364 of that 1,582-page omnibus bill. It comes under Title X of the section on the Defense Department, labeled “Military Disability Retirement and Survivor Benefit Annuity Restoration.” In other words, appropriators reversed the military pension cut, but only for disability and survivor benefits. (Murray and Ryan agreed to roll back this measure, which they claimed was inadvertent, earlier this year.) This is seen as about 10 percent of the overall savings from the pension changes, a fairly infinitesimal $600 million in a country with an annual budget in the trillions.

But what should gall people is subsection (d) on Page 364. “Exclusion of budgetary effects from paygo scorecards,” it reads, adding, “The budgetary effects of this section shall not be entered on either PAYGO scorecard maintained pursuant to section 4(d) of the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010.”

Translating from Congress-ese, this refers to a federal “paygo” law requiring any non-emergency spending to be offset with some budgetary savings of equal value, either through spending cuts or revenue increases. According to this subsection, the restoration of those particular military pension cuts doesn’t have to be scored in this fashion, meaning no offset is required.

From a budgetary standpoint, the impact is extremely minimal. But symbolically, this speaks volumes. First of all, it shows that “paygo” is an extremely flexible principle, and if the spending in question is deemed important enough, Congress can simply write a clause waiving itself from having to enforce it.

Theoretically, that means any additional federal spending could be freed from paygo dictates, which happens to be just what the economy needs right now. Last week’s anemic jobs report and cascade in the percentage of Americans in the labor force revealed continued struggles in the job market. Some economists, most notably Larry Summers, have raised the prospect that the economy is mired in secular stagnation, a permanent malaise that policymakers seem unable to turn around without inviting dangerous financial asset bubbles. Summers believes the only way to reverse secular stagnation while maintaining financial stability is through massive increases in federal spending.

That has not been a viable option in Congress, where House Republicans have demanded deficit reduction rather than expansion. Senate Democrats could not even pass an extension of unemployment benefits, a very real “emergency” for millions of long-term unemployed with no means of income, without pairing it with an offset, and even that bill subsequently collapsed. Similarly, lawmakers could not advance a farm bill without extracting $9 billion from the food stamp program, also an emergency for those desperately poor who need assistance to keep themselves nourished.

No spending, we are told, can escape Congress without the dastardly House Republicans stepping in and forcing offsets. There’s even a federal statute dedicated to maintaining such fiscal responsibility. It doesn’t matter if the spending is worthwhile or even if it fixes an inadvertent glitch; every bit of it must be paid for.

Unless that spending has something to do with the military, that is. Then, politicians in both parties will write a special exemption freeing themselves from having to find offsets.

Again, the particular spending at issue here is around $600 million over 10 years, truly a speck in the federal budget. Of course, that raises the question of why appropriators couldn’t find the money – change in the couch cushions from their standpoint – to simply offset the restoration of funds. And the answer is that they didn’t want to take the time to actually make that happen. This was a priority for military members, and those priorities trump virtually everything else in Washington.

I don’t begrudge military veterans on disability or their survivors from pension benefits they were promised at enlistment; this policy was fairly appalling. If I ran the zoo they would get enough for a stable retirement, just like every American worker whose toil deserves some dignity in old age. But the disparity between how Congress jumps for the needs of the military and how every other employee of the federal government, every long-term unemployed worker, and every food stamp recipient gets treated is striking.

I should add that this largess is not limited to a minor provision for veterans. In fact, the whole military budget will benefit from a bait-and-switch by appropriators. They kept the baseline military budget at $488 billion for the fiscal year, as per prior agreement. But they raised the “overseas contingency operations” budget, money that’s supposed to be dedicated to active war operations in places like Afghanistan, to $91.7 billion, $7 billion over the Obama administration’s 2014 budget request. The clear goal here is to give the Pentagon an OCO slush fund to make up for any reductions in their baseline budget.

So the next time you hear a politician disparage some social service because “we simply can’t afford it,” you now understand the hollowness of such rhetoric. You know that Congress believes anything is affordable as long as it comes wrapped in the flag or wearing the uniform of the Armed Forces. Because you’ve seen Page 364.

Shares