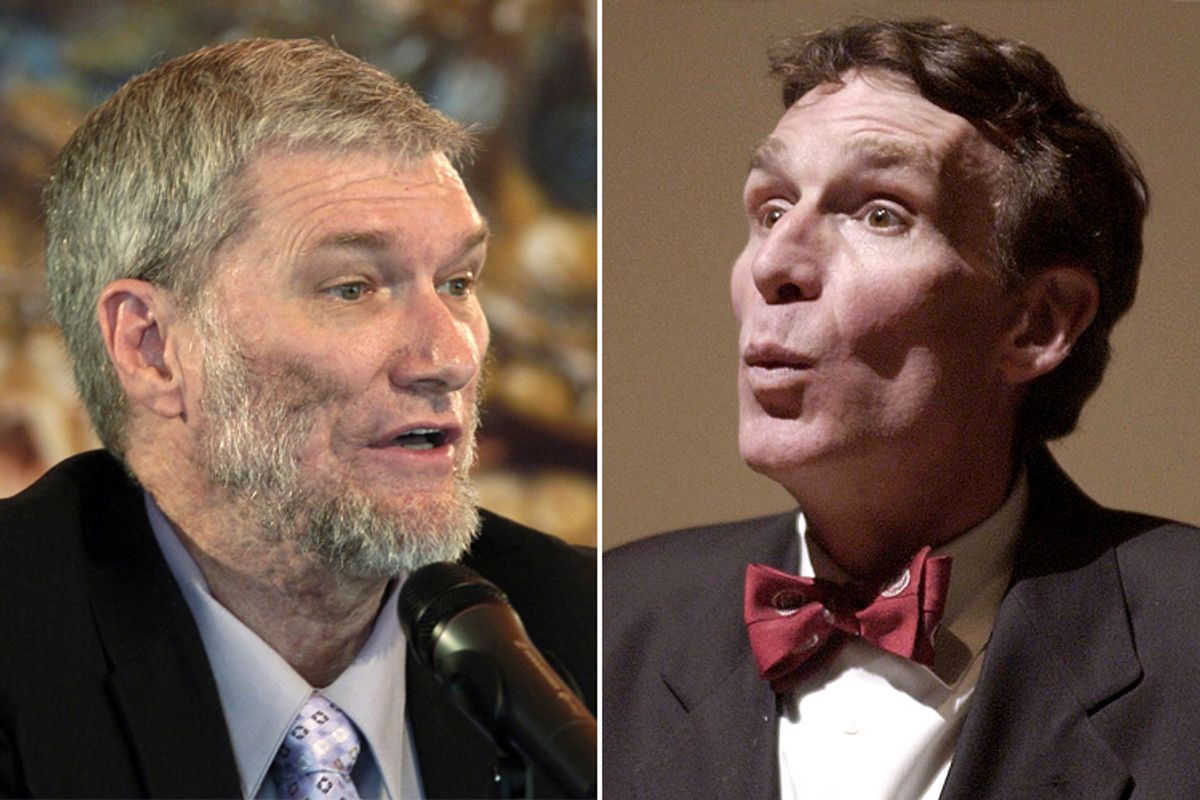

Bill Nye and Ken Ham will be debating creationism on Feb. 4, and it's a bad idea for both scientists and Christians. Ham’s young-earth creationism represents the distinct tendency of American Christian fundamentalists to reject science and use their religion to defend economic ideas, environmental degradation and anti-science extremism. But these views aren’t actually inherent in Christianity -- they've been imposed on the biblical text by politically motivated and theologically inept readers. The solution is not anti-theism but better theological and scientific awareness.

The vast majority of right-wing Christian fundamentalists in the U.S. are evangelicals, followers of an offshoot of Protestantism. Protestantism is based on the premise that truth about God and his relationship with the world can be discovered by individuals, regardless of their level of education or social status. Because of its roots in a schism motivated by a distrust of religious experts (priests, bishops, the pope), Protestantism today is still highly individualistic. In the United States, Protestantism has been mixed with the similarly individualistic American frontier mythos, fomenting broad anti-intellectualism.

Richard Hofstadter’s classic, "Anti-Intellectualism in American Life," perfectly summarizes the American distaste for intellectualism and how egalitarian sentiments became intertwined with religion. He and Walter Lippmann point to the first wave of opposition to Darwinian evolution theory, led by William Jennings Bryan, as the quintessential example of the convergence of anti-intellectualism, the egalitarian spirit and religion. Bryan worried about the conflation of Darwinian evolution theory and capitalist economics that allowed elites to declare themselves superior to lower classes. He felt that the teaching of evolution challenged popular democracy: “What right have the evolutionists -- a relatively small percentage of the population -- to teach at public expense a so-called scientific interpretation of the Bible when orthodox Christians are not permitted to teach an orthodox interpretation of the Bible?” He notes further, “The one beauty of the word of God, is that it does not take an expert to understand it.”

This American distrust of experts isn’t confined to religion. It explains the popularity of books like "Wrong" by David Freedman (a book that purports to show “why experts are wrong”) that take those snobbish “experts” down a peg. The delightfully cynical H.L. Mencken writes,

The agents of such quackeries gain their converts by the simple process of reducing the inordinately complex to the absurdly simple. Unless a man is already equipped with a considerable knowledge of chemistry, bacteriology and physiology, no one can ever hope to make him understand what is meant by the term anaphylaxis, but any man, if only he be idiot enough, can grasp the whole theory of chiropractic in twenty minutes.

Thus, an American need not understand economics to challenge Keynes, nor possess a PhD to question climate change, nor to have read Darwin to declare his entire book a fraud. One need not read journals, for Gladwell suffices, and Jenny McCarthy’s personal anecdotes trump the Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences.

The irony of modern American Christian right-wing fundamentalism is that, for all its talk of tradition, it is a radically new way to read the Bible. The strict constructionist, or literal fundamentalist, biblical method of interpretation was invented in the 19th century. America at this time experienced rapid social change that played a key role in creating the fundamentalism that now lies at the core of the religious right. The Industrial Revolution gave rise to the idea that technological progress is the way forward. American Protestants worried that all this science would encroach on their religious beliefs, so they turned to the Bible as the source of all knowledge -- scientific and spiritual. During a time when Darwin’s followers were trying to explain everything in terms of evolutionary theory, American Protestants refused to look for truth outside their interpretation of Scripture.

In "Fundamentalism and American Culture," George Marsden describes fundamentalism as “essentially the extreme and agonized defense of a dying way of life.” The American Protestant response to the Industrial Revolution was engendered by the fear that a small cabal of experts would dictate to Americans how to live their lives and that science would somehow replace their religion. In truth, the Christian tradition provides little support for the fundamentalist doctrines that arose during this period. Augustine believed that science and religion need not be in competition, and the Catholic Church has long held that evolution does not contradict the Church’s teachings. Fundamentalists who deny climate change and evolution have simply read their simplistic understanding of science into biblical texts.

Because the “fundamentalist problem” is not rooted in religion, the answer can’t be found in anti-theism, the preferred response of commentators like Bill Maher, Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins. Rather, American Protestants must learn to read the Bible as a religious text rather than a series of logical premises to be proven. The irony of debates like the one between Bill Nye and Ken Ham is that they pit two fundamentalist readers against each other. The fundamentalist Christian and the atheist both read the Bible as a series of falsifiable propositions -- what Terry Eagleton calls the “Yeti” theory of belief. Disproving the creation narrative should strike any theologian as absurd -- the way a literature professor would react if a student claimed to have “disproven” "Sons and Lovers."

Religious conflicts can serve to obfuscate base political or economic motives. Christianity was used to justify slavery in the South, but it’s doubtful that without the Bible, Southerners would have freed their slaves (it may be worth noting that science was also used to justify racism, most famously documented in Stephen Jay Gould’s "Mismeasure of Man").

In the same way that racism was read into the Bible, modern American Protestant positions, like climate change denialism and anti-evolutionary thinking, are being imposed on Scripture. The religious justification for denying climate change is tenuous, while the economic justification, for someone worried about keeping their job or filling up their tank, is not. Americans whose economic interests rely heavily on fossil-fuel-intensive industries aren’t keen to lower their standard of living by abandoning coal.

The upcoming Nye/Ham debate, and other debates like it, are merely reiterations of the classic debates between Adams and Jackson, Burke and Paine, Lippmann and Chomsky: the philosopher-king vs. the democrat. By singling out religion as the genesis of these anti-intellectual outbursts, the New Atheist movement only takes us away from the solution: divorcing religion and science. By claiming that religion needs to be abolished, the New Atheist movement justifies the worst fears of the religious. When a religious person makes a political assertion or an economic argument or a claim about science, it is exactly that: a disprovable assertion. Within religious circles, fundamentalists must be challenged (with appropriate love) for manipulating true religion.

The religious right’s stance on climate change, economics and evolution is not informed by their religious beliefs. Rather, these political and economic views are imposed on Scripture, which is often read without theological rigor. It is not religion that is the problem, but rather the use of religion as an ideological weapon. But to respond by using science as a weapon is equally problematic.

The best way to address the problem is to confront the underlying political and economic concerns that are obscured by religious dogma, rather than attacking the religion directly. Our problems require an entirely new political and economic paradigm, one that rests on understanding and empathetic action between people of all faiths. Religious reformers, concerned environmentalists, scientists and economists must work together toward a more sustainable future. Bill Nye is intensely concerned about climate change and evolution, as are we. He should therefore ally himself with sane religious leaders, rather than debate fundamentalists.

Shares