I’m a nerd.

OK, a lot of people say that these days. But I really am. I was hired as a computer programmer for a national laboratory at age 15. I have seen every existing episode of "Doctor Who" (classic and modern). I study orbital dynamics as a hobby. My idea of a good time is sitting down and drawing on that knowledge to imagine a space mission from beginning to end, getting as many details right as I can.

Pretty frickin’ nerdy, right?

On top of that, as you might expect, I’ve also been a science fiction fan ever since I was old enough to read, which was when I started plowing through my dad’s nearly infinite collection of Heinlein, Clarke, Asimov and all the other great authors of the genre.

One day, in between doing highly charismatic non-nerdy things, I started working up a manned Mars mission in my head. I even wrote my own software to calculate the orbital trajectory my imaginary crew would take to get from Earth to Mars. And not some boring Hohmann Transfer, either! I envisioned a constantly accelerating VASIMR powered ship, which -- ahem. Sorry, got carried away. Anyway, I had to account for failure scenarios on their surface mission. What if something went wrong? How could I design the mission so the crew would have contingency plans? What if they had multiple failures, one after another, that ruined those contingency plans?

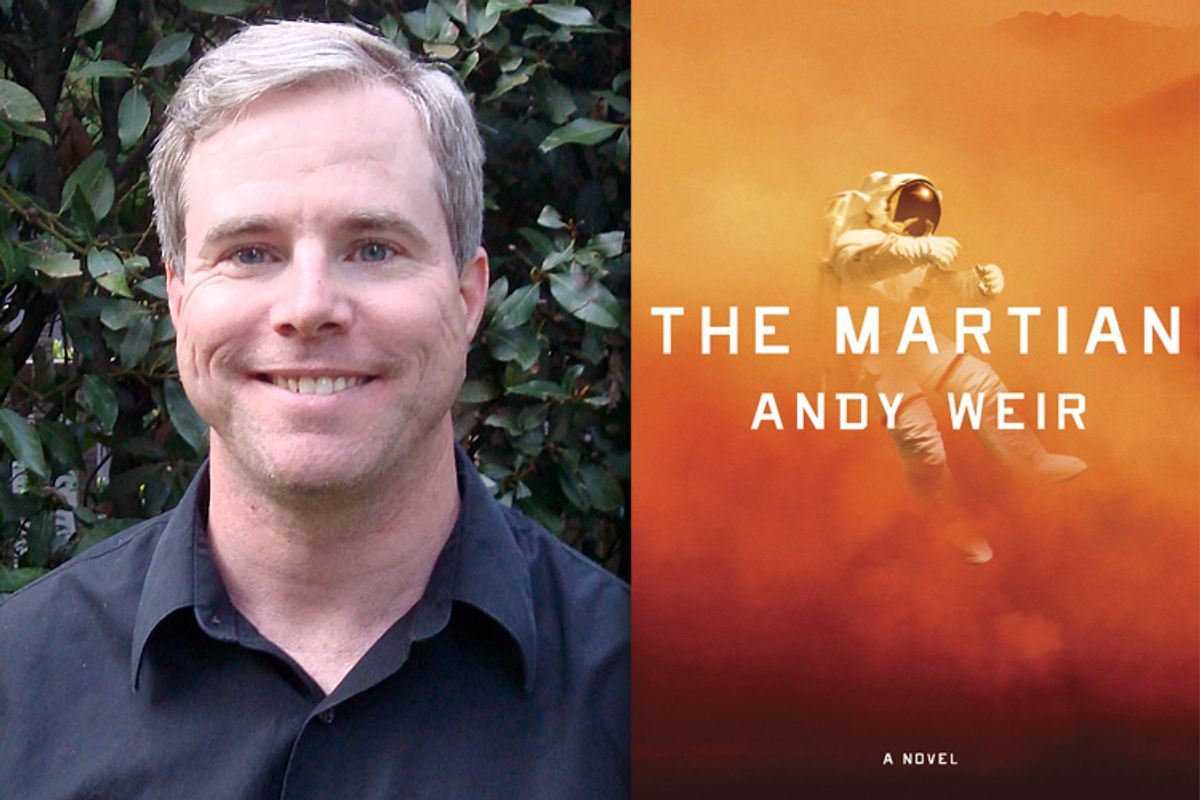

While working that out, I started to realize their increasingly desperate solutions would make a pretty interesting story. That’s when I came up with the idea for "The Martian."

Oh, one more nerdy hobby I forgot to mention up top: I’ve also been a wannabe writer since I was a teenager. I wrote countless short stories and even penned two complete books before "The Martian." My first book was so horrible I have deleted all copies of it. Thankfully, it was before the Internet so there are no lurking caches of it anywhere. I made up for that failure by writing a second book that was also crappy. This time I resolved to do better.

So I created an unlucky main character named Mark Watney and then spent 368 pages making his life a living hell. He’s stranded on Mars, his crew has evacuated and thinks he’s dead, and he has no way to contact Earth.

Even though my plan was to torture Mark, I knew from the very beginning that I didn’t want my hero to suffer one unlikely, disastrous coincidence after the next. I decided that each problem Mark faced had to be a plausible consequence of his situation — or, better yet, an unintended consequence of his solution to a previous problem. He could suffer an equipment failure in machinery stretched beyond its intended use, but he couldn’t be struck by lightning and then have a meteor crash on him.

I also really wanted Mark to be fallible. Yeah, OK, I made him smarter and more resourceful than you or I would be in that situation. But hey, it’s only realistic to do that when your hero’s an astronaut. Nevertheless, in a situation where even the smallest mistake can be catastrophic, and you’re forced to make life-or-death decisions every day, even the brightest person is going to slip sometimes and invite disaster.

Was I worried about whether my scenario would give me enough plot to sustain a novel? Did I wonder if being that realistic would make a boring story?

Hell yes.

But as I wrote, I bungled my way into a revelation: Science creates plot! As I worked out the intricacies of each problem and solution, little details I wouldn’t have otherwise noticed became critical problems Mark had to solve. No need for meteor strikes — the surprises, catastrophes and narrow escapes were coming fast and furious on their own.

And the deeper into the book I got, the more excited I became, because I found that I was arriving at that place writers dream of: I was coming up with plot twists that genuinely surprised me, yet felt totally organic to the situation I’d dreamed up. This allowed me to do what writers treasure more than anything else: Catch the reader off-guard. There’s nothing better than knowing you’re going to outwit the reader. And the type of people who read sci-fi are very difficult to outwit.

I originally wrote "The Martian" as a free serial novel, posting one chapter at a time to my website. Thanks to my previous attempts at writing, I had a small but loyal following of readers who read each chapter as I finished it. This turned out to be an amazing process. I got tons of feedback as the story progressed, and I fine-tuned the novel as I went along.

Eventually, my website readers started bugging me to put the book up on Amazon so they could read it on their Kindles. So I formatted the book, slapped a public-domain photo of Mars on the cover, and tossed it on up there. I priced it at 99 cents because Amazon wouldn’t let me make it free permanently.

After that, things got a little crazy. Next thing I knew, it was one of Amazon’s top five sci-fi bestsellers, and tens of thousands of people had downloaded it. Then a literary agent and publishers came knocking, and movie studios started bidding on the film rights. And now, it’s going to be hitting bookstore shelves not just in the U.S., but in 18 other countries.

In those months since I first started putting chapters up online, I’ve received fan emails from astronauts, people in Mission Control, nuclear submarine technicians, chemists, physicists, geologists and folks in pretty much every other scientific discipline. All of them had nice things to say about the book’s technical accuracy, though some of them also sent formal proofs detailing where I’d gone wrong. I corrected those problems (mostly) in the final edition that went to print.

Even more satisfying than those responses to the science, though, were all the readers who told me I’d succeeded in my other goal, the one that really made me tremble in fear as I was writing: People kept telling me how exciting and suspenseful and surprising the book was. My favorite fan mail is the kind that starts “Normally I don’t read science-fiction, but …”

That response is pretty damn incredible, considering all I really did was write about how much I love science — albeit while tormenting my main character with the constant threat of death.

Eh. Mark’s a smart guy. He can handle it.

Shares