Across the country, state budget writers are on firmer ground as 2014 begins because Congress raised taxes on investments and the richest Americans when they compromised over the now-forgotten “fiscal cliff” standoff in late 2012.

Across the country, state budget writers are on firmer ground as 2014 begins because Congress raised taxes on investments and the richest Americans when they compromised over the now-forgotten “fiscal cliff” standoff in late 2012.

In recent weeks, national news organizations have reported that governors and legislators in blue and red states are jockeying over how to spend better-than-expected revenues. In ultra-red Kansas and deep-blue New York, governors on opposite ends of the spectrum want to expand early childhood education. In Democrat-majority California, Gov. Jerry Brown is looking at a putting extra cash into a rainy day fund while legislators want schools and safety nets restored. In other states, the recovery has led to calls for more spending on job training, public health, cheaper higher education, roads and tax cuts.

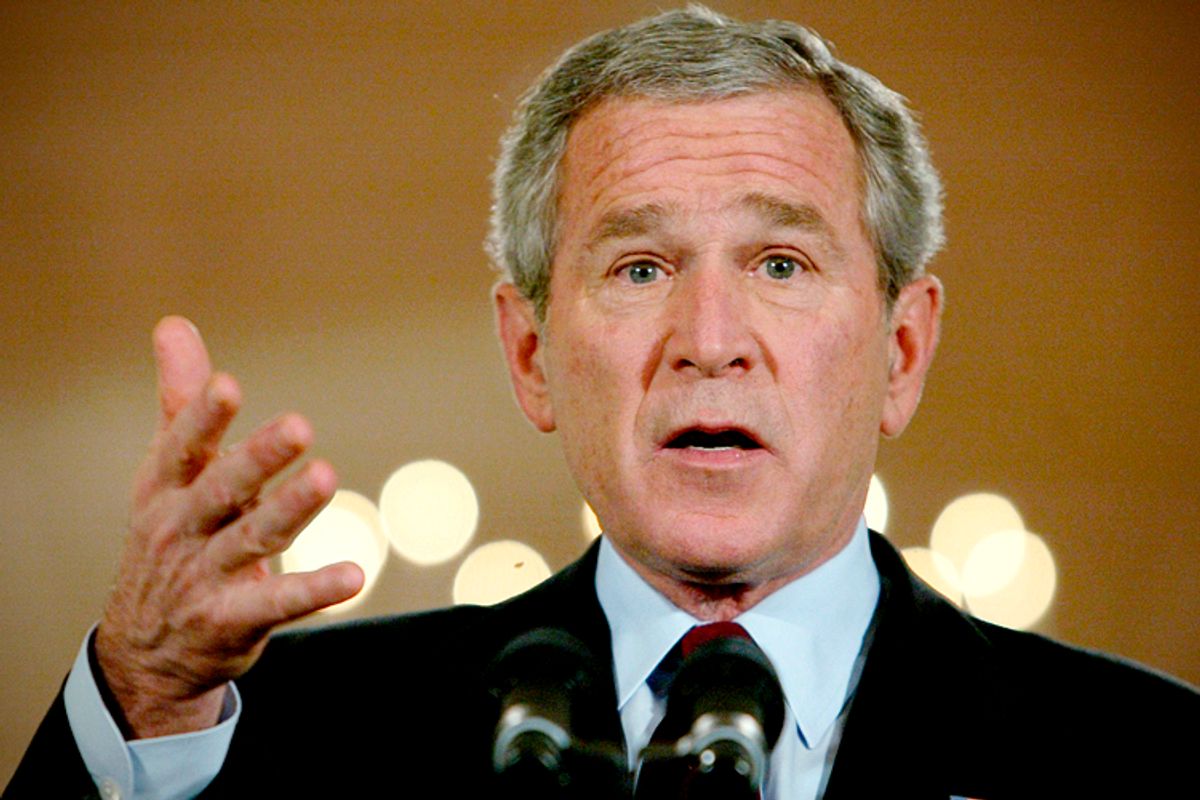

The reasons for the better-than-expected revenues are a mix of factors: higher income tax revenues, growing sales tax revenues, and conservative budget forecasting—prompting the press reports that revenue forecasts are being exceeded. But where reporters generally stop explaining what’s behind the revenue surge is noting that 2013’s big bump in state revenues—5.7 percent nationally—mostly came from ending some Bush-era tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans and Wall Street investments.

It’s easy to forget the political fight over whether the Bush administration cuts should be kept or allowed to lapse, since the House GOP subsequently allowed across-the-board cuts to take place—the sequester—and then in October forced a federal shutdown. Yet congressional Republicans compromised with the White House in late December 2012 and passed a bill raising income tax rates for the top bracket from 35 percent to 39.6 percent, starting in 2013. The rate on longterm capital gains was raised from 15 percent to 20 percent for incomes in the highest income tax bracket, which is 39.6 percent. Also, a 3.8 percent surcharge was added to unearned income—investments—and an additional 0.9 percent was imposed for individuals making more than $200,000 and couples earning more than $250,000.

These tax changes prompted a lot of wealthy people to move their money around in many tax-avoiding ways, as accountants advised at that time. Their response may have led to some of last years big stock market gains, the Wall Street Journal recently suggested. However, there was no avoiding larger income tax bills for many well-off people last year, because most state income taxes are calculated as a percentage of what's owed to the federal government. State revenue from those assets fell somewhat last year, experts said, but did not disappear entirely 2014’s revenue estimates. (Because federal and state fiscal years do not overlap with the calendar year, the biggest revenue bump was felt the first year the Bush tax cuts ended—2013.)

Some states are especially dependent on taxes from investment income, such as California, New York, Connecticut and Minnesota. In California, Gov. Brown emphasized this point when he used a chart illustrating fluctuations in capital gains revenue as he unveiled his latest budget in early January, saying that California needed a bigger rainy day fund. Since then the stock market has fallen, which strengthens Brown’s call for a bigger reserve. If he is re-elected this fall, as most analysts expect, and he boosts state reserves, Brown would have billions more to work with in his final term.

Most states rely on income and sales tax for about two-thirds of their revenue. Income taxes account for slightly more than a third of revenues in the 45 states that have state income taxes, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers. Typically, states calculate their income tax levy as a percentage of the federal tax paid, which is how state coffers swelled in 2013.

Sales tax accounts for the next third of state revenues, NASBO said. These revenues have been growing slowly as the economy recovers from the Great Recession, but they have not spiked like revenues from changing capital gains tax rates. The rest of the revenue picture comes from a mix of other state taxes and fees, with corporate taxes generating less than 10 percent of revenues. Gas taxes typically go to dedicated transportation funds, so they do not effect General Fund projections.

While the post-recession economic growth has varied from state to state, it obviously has been sluggish. Sales tax data also is much more in the public’s view than capital gains data. That is because sales tax data is generated and reported monthly, compared to income tax data—of which capital gains is one element—that’s usually reported quarterly or annually.

As a result, state officials who compile budget forecasts have been very conservative. For example, revenues were forecast grow by 5.3 percent in 2013 and only 1.3 percent this year, NASBO said. Those cautious estimates create a low threshold that allows the press to say that states are beating their revenue forecasts.

On the spending side of the ledger, states are generally proposing spending increases in the 2-3 percent range, which is about half the historic average for the past 50 years, NASBO said.

The big takeaway from this discussion is taxes matter, especially tax rates for the richest Americans. When the Obama Administration and congressional Republicans raised taxes on the wealthiest Americans in 2012, one longer-term effect that we can now see is that restored fiscal stability in the states.

There still are untapped big revenue sources out there. Imagine how government’s finances would be if Congress closed corporate tax loopholes—instead of considering a growing idea in Washington that Obama supports: amnesty for corporations keeping an estimated $2 trillion offshore to avoid U.S. taxes on their profits.

Shares