What with everything else going on, you might not have realized that Earth's currently undergoing a mass loss of life -- the so-called Sixth Extinction. The Fifth Extinction was the asteroid that collided with Earth some 66 million years ago, killing off the dinosaurs. This newest extinction is far less dramatic, at least in the fire-and-brimstone sort of way -- which explains how it's been happening right under our noses.

Nonetheless, by the end of this century, scientists believe, up to 20 to 50 percent of the plant and animal species on Earth could be gone forever. Only there will be no giant asteroid to blame for the loss. This time -- in a "Twilight Zone"-worthy twist of fate -- the giant asteroid is us.

Ever since we first began to migrate and multiply, we humans have been crowding out everything else living on Earth, leading for thousands of years a (largely) unintentional campaign against other species that, in more recent times, has gotten much, much worse.

“Right now,” journalist Elizabeth Kolbert writes, “we are deciding, without quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open and which will forever be closed. No other creature has ever managed this, and it will, unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy.”

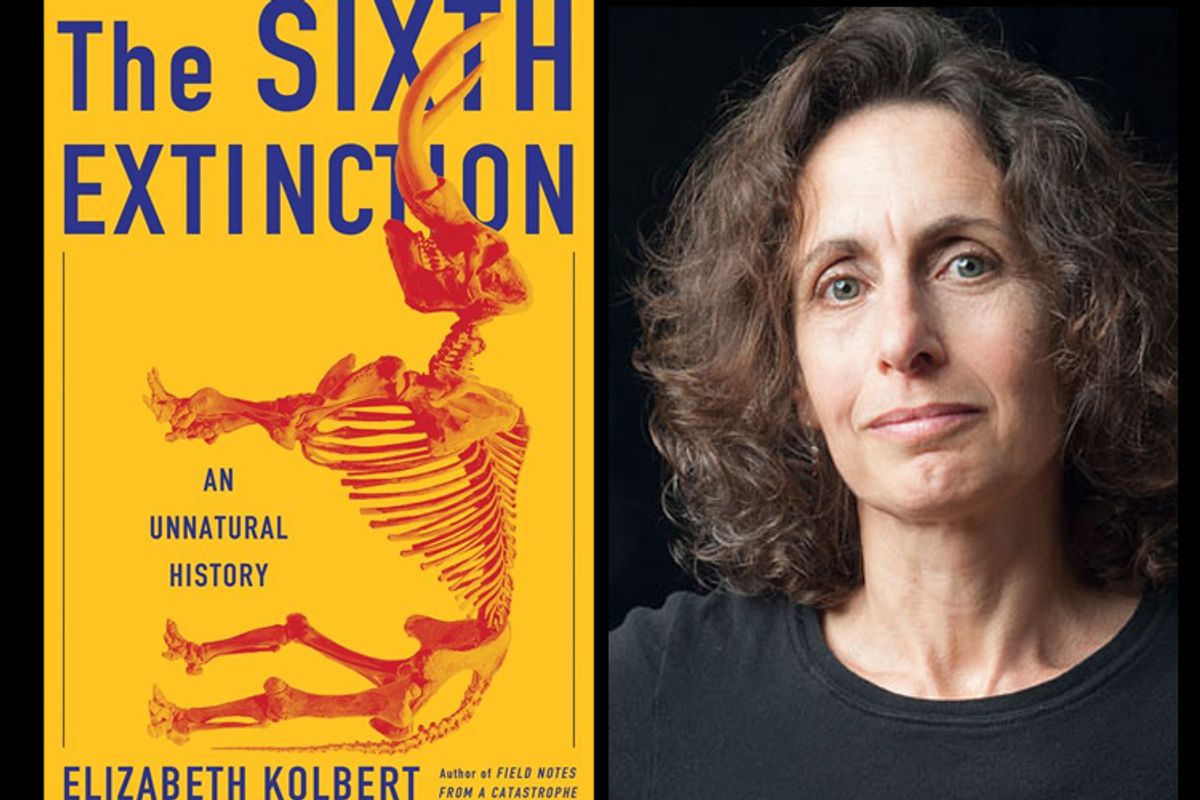

With remarkable journalistic prowess, Kolbert, a staff writer at the New Yorker, traveled the world to document mankind's undeniable role in this world-changing catastrophe, drawing insight from the Amazon rainforest, the Great Barrier Reef and the changing landscape of the United States. "The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History" underscores the global scale, and urgent importance, of everything she saw.

Kolbert spoke with Salon about extinction's controversial history and uncertain future. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Back in 2009 you wrote a New Yorker article entitled “The Sixth Extinction?” I noticed the question mark’s been removed from the book. Are scientists more certain now that this is something that’s happening? What does that consensus look like?

I don’t want to claim that a tremendous amount has changed since 2009. I think there is a pretty broad consensus that we’re in the midst of a mass extinction, or a certainly a period when extinction rates are way, way above normal for the geological record, what’s called “background rate.” Now, whether we are on the verge of a major mass extinction, the beginning of one, or in the middle of one, different people have really different ideas about how you can calculate that. We get past mass extinctions from the fossil record and we don’t have the fossil record of the present yet, so it’s not that easy to compare apples to apples.

But scientists are definitely convinced that humans are causing this, that it isn’t just something that happens cyclically?

Oh yes, absolutely -- it doesn’t happen cyclically. There was a theory at one point that gained a certain amount of notoriety, maybe 20 years ago, that maybe there were these cyclical extinctions that had to do with -- I know it sound kind of crazy and sci-fi-y -- but that maybe we passed through some kind of asteroid belt that caused a lot of damage every 26 million years. That theory has been pretty thoroughly debunked, even by the people who forwarded it at the time. I don’t think anyone subscribes to it anymore.

The general consensus is that these events are not cyclical at all; they’re quite random, and there’s no one cause. In fact, some people have concluded what is so dangerous about these events that turn out to be mass extinctions is that they’re unprecedented. They’re just weird, out-of-the-blue events. So in a sense, we, humans, are a weird, out-of-the-blue event.

Right, we’re kind of like that giant asteroid that came down and killed the dinosaurs, but at the same time the effect that we’re having is a lot slower.

That parallel is definitely being drawn. And in a geological sense, well, an asteroid impact is really, really fast -- but we’re really, really fast, too. We’re not quite as fast as an asteroid, but we’re still fast. So, for example, what we’re doing to the climate and to the oceans -- pouring CO2 into the oceans, causing this phenomenon known as ocean acidification -- we’re doing that quite possibly faster than it has even happened before. We’re releasing CO2 at a rate that has never happened before in Earth’s history. So we are pretty fast.

I guess from a human perspective it’s hard for us to recognize how rapidly that’s happening…

Yes, exactly, and that is another interesting part of the sort of mismatch of all that. We are in the middle of it, and yet we’re doing things which to us seem incredibly ordinary. Well, okay, there are 7 billion people and X billion of them are driving cars, and that seems really ordinary, but in fact, geologically speaking, what’s happening by transferring all that CO2 from underground, basically, to the air, is really, really unusual in geological terms.

And it’s not like you can watch things happen from one day to the next -- although in some sense we almost are. Things are happening at a rate that many scientists will tell you they were taught in graduate school was impossible, and now they’re seeing them actually happen.

So it’s something that’s been accelerating?

Yes. An Australian scientist coined this term “the Great Acceleration,” and what he’s referring to is the way in which human impacts are just ramping up, in line with how much of the world’s resources we’re consuming, how many of us there are -- all of these things are growing at a very rapid clip. He dates it to end of World War II.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about evolution, which is still being hotly contested in some circles. For a long time, the idea of extinction was just as controversial, right?

It’s a really interesting history, and the whole first part of the book is about how this concept of extinction came into being. Extinction, interestingly, predates evolution as a generally accepted concept by about half a century and it was first really introduced in post-revolutionary France by a French naturalist named Georges Cuvier. Up until that point people sort of figured, well, if something had existed, it still existed, because that was the way of creation: why would the “Creator” create something only in order to do away with it?

In line with that, for example, Thomas Jefferson expected when he sent Lewis and Clark out to the West that they would actually find a mastodon running around. He was quite interested in fossils and natural history, but he really couldn’t believe that these great beasts weren’t out there somewhere.

Cuvier came to the conclusion, based largely on the fact that no one had ever seen these animals, that they were gone. He went so far as to posit that there was this whole “lost world,” which he then succeeded in really documenting, by uncovering lots of interesting and weird fossils. That was really the beginning of paleontology.

Today, you write about the extraordinary means that conservationists are going through to save some of these species that are close to extinction. The book has a great line: “Such is the pain the loss of a single species causes that we are willing to perform ultrasounds on rhinos and hand jobs on crows.” Do these efforts strike you as heroic or, given the scale of things, kind of futile?

How about both? I mean, a lot of the heroic things people have done throughout history have had a futile element to them. But I think they are heroic. I really admire all the people I met, who are giving hand jobs to crows and ultrasounds to rhinos, and who are also all over the world trying to stop rhino poaching and trying to protect some of the last uncut forests -- all of the conservation efforts people are really devoting their lives to.

I respect them a lot, but I think even they would say, you know, these things are coming from all sides and where is all of this going? I think a lot of times in the conservation community, we turn around and try to solve one thing and something else comes at us. The world is just changing so fast. So, for example, you might preserve a habitat for some animal that’s endangered only to find that that species really needs to move somewhere new because the climate is changing. So the challenges are really multiplying.

There can be controversy, too, over people’s priorities. You know, we really want to save the cute species.

That’s a question that is a little beyond my pay grade, to be honest. The question of how much resources, for example, go into saving these, as you said, charismatic species as opposed to just trying to save the habitat. These animals are iconic; they’re the things that everybody knows, and they have an emotional tug. If you show people a picture of a baby panda, that has a lot of appeal as opposed to a picture of that worm or that insect that is going extinct because its habitat is being destroyed.

But the question of whether those are really the best use of conservation money, dollar for dollar getting the biggest bang for your buck -- those are tough questions. But the sense from the panda campaign is that those animals need a lot of territory, so if you can preserve big animals that roam around a lot, then chances are you probably are also preserving a lot of the smaller things that you don’t even know about.

In the book itself, you stay away from presenting any definitive solutions, or predictions about what’s going to happen. Do you have any thoughts about how people can best respond to what’s happening?

I really wrote the book -- in the way that journalists do things -- because I thought it was important and I felt that this is information that people really ought to have. And to go to the next step to sort of prescribe the answer for the world, that’s once again a little beyond a journalist’s role.

So I guess I’m going say that I feel my role is to bring this before people. I feel that there is way too little awareness of what’s happening in the world, and in part because of what we were talking about earlier -- that what seems really ordinary in the course of everyday life turns out to be extraordinary in the history of the planet. And to bring that home to people, in a way, by using some of these examples of organisms that are on the brink.

But I consciously didn’t say “Now here are the 10 things that you can do” because the 10 things that you can do are not commensurate with the issue at hand. So I sort of leave that next step to the reader.

Shares