Women read more books than men. Yet every year, according to counts conducted by VIDA, most major publications run more book reviews by men than by women, and review more books by men than by women. In 2013, for example, the London Review of Books had 195 male book reviewers to 43 women reviewers: a ratio of almost 4-to-1. The New York Review of Books was in the same ballpark, with 212 male reviewers to 52 female ones. In a world with more female readers than male ones, how does that happen?

The BBC had a recent discussion of this very question. The segment included a statement from the London Review of Books (transcribed independently here), in which the publication tried to explain why 82 percent of its articles have been written by men. According to editor Mary-Kay Wilmers, quoted in the statement:

I think women find it difficult to do their jobs, look after their children, cook dinner and write pieces. They just can’t get it all done. And men can. Because they have fewer, quite different responsibilities. And they’re not so newly arrived in the country. They’re not so frightened of asserting themselves. And they’re not so anxious to please. They’re going to write their pieces and to hell with the rest. And I don’t think women think that way.

The LRB's position appears to be that maybe, eventually, women will become less domestic and assert themselves more, and then they'll have more essays in the LRB. In the meantime, the LRB says, there will be no "quotas" and no "positive discrimination." They will, in short, do nothing to increase the number of women writers, because the lack of women writers is the fault first of society and then of women themselves. It is not, certainly, the fault of the LRB — or of all the other publications that don't publish many women writers either.

What's missing here is a sense that who writes for a publication is actually affected by editorial policy in lots of ways. As just one example, I would point to the one genre that the LRB and most other serious publications treat as anathema: romance.

Of course, not all women even like romance, let alone write about it. And covering romance wouldn't solve big publications' gender problems -- to do that, they'd need to achieve real parity across categories. But these publications' general refusal to cover romance at all speaks to larger biases.

Excluding romance is excluding not just some books, and not just a lot of books, but the largest chunk of books. The Romance Writers of America report that in 2012 romance sales hit more than $1.4 billion. That's 16.7 percent of the U.S. consumer market in books, the single largest slice for any segment – a third larger than the inspirational book market and roughly equivalent to sci-fi and mystery sales combined, according to Valerie Peterson at About.com. Moreover, that market is primarily women: Surveys tend to put the share of romance readers who are female at between 80 and 90 percent. And the overwhelming majority of romance novels are also written by women.

Women, then, read romances and (as a cursory poke around the Internet or GoodReads will tell you) write about romances in huge numbers. That writing does not appear in serious publications, though, because serious publications do not write about romance novels.

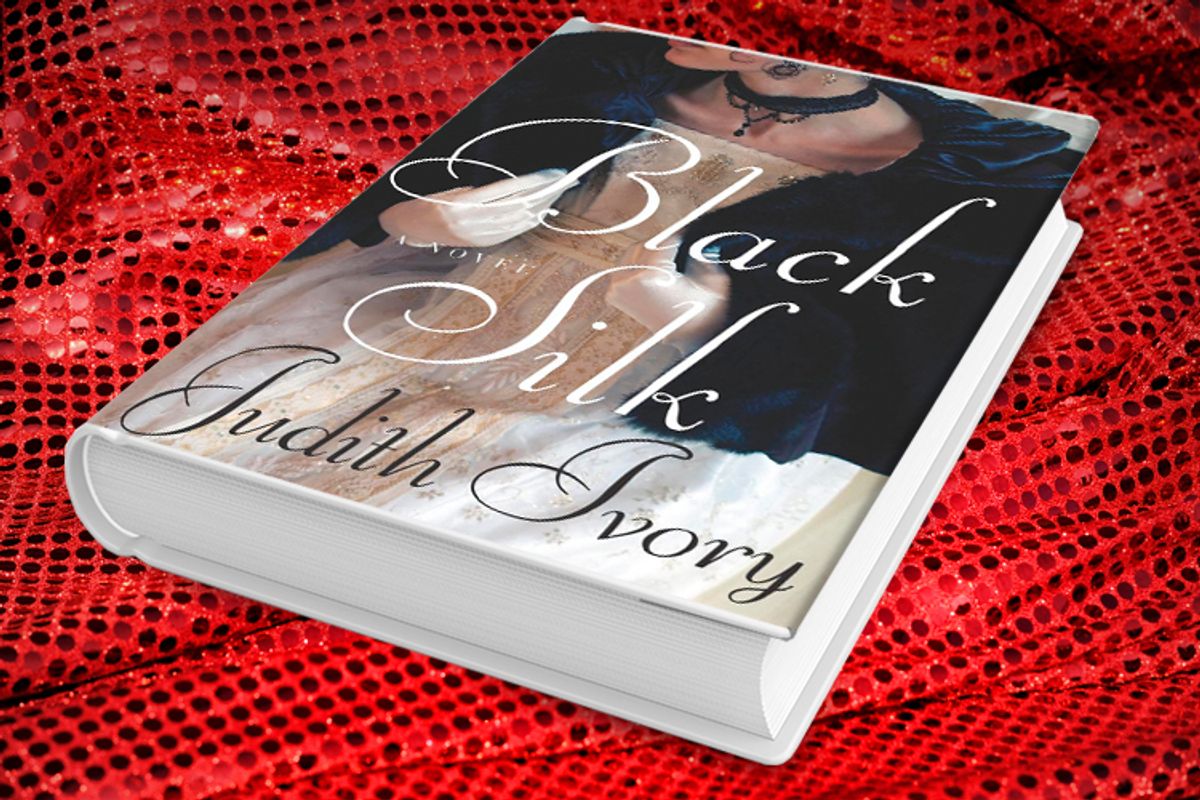

Of course, these publications might claim they exclude romance novels not because they are often by women or appeal to women, but rather because they're frivolous, poorly written crap. And some romances are crap; "Fifty Shades of Grey" is a terrible book, and I couldn't even manage three pages of the last Nora Roberts book I tried. But there are plenty of mediocre books of all sorts, up to and including literary fiction. Is the self-conscious virtuosity of Jonathan Lethem's "As She Crawled Across the Table," with its thunking ironies and predictable magical realist absurdities, really any less formulaic than romance fiction? Certainly, the book's exploration of love and creation seems clumsy compared to Judith Ivory's Regency romance "Black Silk" and its meta-narrative. The heroine, Submit, takes over the writing of a serial begun by her recently dead husband, Henry, which caricatures the scandalous career of his former ward, Graham. In becoming Graham's author, Submit becomes the author of the book she's in as well, so writing one's love (both as parody and as romance) becomes writing oneself. And that writing and creating is done slowly, languorously, the hesitance of creation treated as itself a sensual pleasure:

She touched furniture and doors, knowing she was going to make this room, that couch, that Chinese vase into a paper backdrop. Her tour had an odd, almost dizzying effect. A room would suggest ideas or suddenly pop out, amazingly familiar from already having been visualized within the loops and jags of Henry's close scrawl. There was something circular here, a fiction come to life, while real objects suggested ways to build more fictional plausibility.

Note again that Submit is writing in the "loops and jags" of her much older husband; the power of writing is figured specifically as patriarchal. Taking up the pen is a masculine power, which both frees her and turns her into Henry's creature. The very deliberately named Submit both embodies empowerment and critiques it.

Again, I'm sure there are many people — and indeed, many women — who prefer Lethem to Ivory. The point isn't that all people everywhere should like what I like. The point is that certain authors and certain perspectives are excluded before a conversation can even begin.

The typical excuse for that exclusion is genre, not gender. But those two words have a common root, and are intertwined in many ways. Romance is seen as unserious and frivolous because women are seen as unserious and frivolous, and romance is written largely by women, for women, about concerns traditionally seen as feminine (Jennifer Weiner and Jodi Picoult have made a similar argument about commercial fiction by women). I wouldn't argue that the LRB and similar publications need to cover romance if they want to get more female book reviewers. But I would say that the mind-set that says that romance novels are automatically trash is linked to the mind-set that prevents these venues from publishing more women writers.

Shares