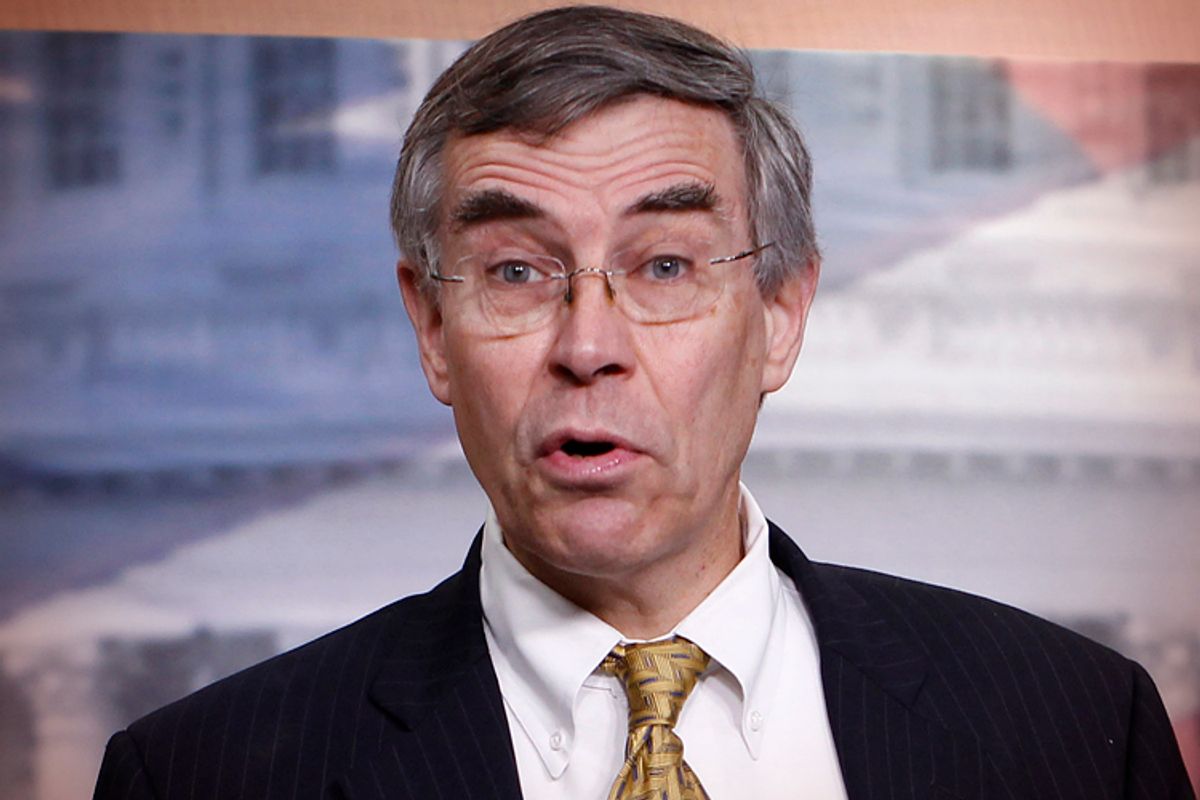

“Millions are already dying, or have died, as a result of changes in the climate,” Rep. Rush Holt, D-N.J., told Salon.

Holt, a plasma physicist and eight-term congressman (and five-time "Jeopardy!" champion), last month announced he’ll leave the House in January. For “future generations, who will pay an even greater price than the current generation from climate change,” Holt told Salon late last week, “it will be hard to explain to them the inaction of America and the U.S. Congress.” A condensed version of our conversation – on climate change, the Keystone Pipeline and colleagues who “don’t really have a clue of how you sustain a productive science enterprise” – follows.

You chair the House Research and Development Caucus. Scientific studies are often among the examples of government spending that get attacked from the right. In the 2008 campaign, Sarah Palin gave “fruit fly research in Paris” as an example of taxpayer dollars going to “projects that have little or nothing to do with the public good.” As a scientist and a politician, how do you respond to those kinds of critiques?

Well, for some of the more inane criticisms I just laugh …

There is, you know, the “Proxmire Effect” -- referring back to Sen. Proxmire, who used to ridicule serious research that had funny-sounding titles. And you know, he was wrong much more often than he was right. It’s true that some research is unproductive. Some of it is even ultimately misleading. But the very idea of peer-reviewed research, you know, research that is guided by the conventions and the practices of the discipline -- and I emphasize the word “discipline” -- and that is chosen and supported by peer review, is very important to our success as a nation …

Much of our economic growth has come from the fruits of research … We need to maintain the research enterprise. We need to invest in the research infrastructure, beyond just the individual projects. And we should rarely, rarely substitute political judgments on the validity or worthwhileness of a project for the peer review, because that gets at the heart of the very process of research that we need to sustain.

You know, I find most members of Congress -- like most citizens -- actually value science, they understand that the payoff from science research is large, but, you know, they appreciate and enjoy the fruits of science but don’t really have a clue of how you sustain a productive science enterprise.

In 2012, you told a Princeton crowd, “I wish we could get more Americans and, hence, their representatives thinking like scientists, which means basing our conclusions on evidence.” Where do you see representatives in Congress not basing their conclusions on evidence?

Big things like climate change, and the way we produce and use energy, and … smaller things like … the energy consumption or the energy inefficiency of light bulbs …

Certainly when you have elected representatives … inventing ideas about a woman’s biology … it’s not just that they didn’t take sex education classes in school. It’s that they’re just not grounded in evidence …

I am not saying that scientists are smarter or wiser than other folks. But there are habits of mind: you know, a deep appreciation of evidence; an ability to deal with probability and statistics, to be alert to cognitive biases and tricks that our minds play on ourselves; … a willingness to accept tentative conclusions and accept … the uncertainty of these scientific conclusions -- not as reason for inaction, but a way of finding the best path forward …

After the electoral errors of 2000 … Congress passed an election reform bill and pushed ... the voting districts in America toward unverifiable electronic machines … They were sold a bill of goods, essentially, by the voting machine manufacturers … No one involved in writing the legislation had bothered to ask …“What are the results? How do we know that your machine records the results that the people think they’re casting?” And it turns out there is no way to audit the machines …

Just some critical thinking; you wouldn’t have to know anything about the software, or about the electronics of the machine, to be able to ask the kinds of questions that any scientist would ask …

If there’s an error in the software … or if the voter does something a little out of the ordinary … or if some malicious person actually hacks into the software to change the votes, no one will ever know … And scientists got that immediately, but those who wrote the legislation didn’t get it immediately. And some of them still don’t, actually.

Debating climate change on "Meet the Press," Marsha Blackburn, the vice chair of the Energy and Commerce committee, said that “when you look at the fact that we have gone from 320 parts per million to 400 parts per million, what you do is realize it’s very slight” and that “there is not consensus.” What do you make of those arguments?

Well, there is very strong consensus in the scientific community that human actions -- primarily the burning of carbon -- have changed the climate of the earth, and changed it for the worse, if you think that it is worse to have higher costs in lives and dollars …

To deny it is not to deny a few facts, or to question a few conclusions. It’s really to deny the entire scientific enterprise -- you know, the validity of the entire scientific enterprise …

If two kids are on a seesaw, and you add only a t10-pound weight to one end … If they were balanced before, it’s going to go down. It’s not, “It’s gonna go down 10 percent” – no, it’s gonna go down. You know, it’s gonna settle all the way to the ground.

So it’s not … how many parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere we’ve added. It’s: What’s the effect of that? And that effect is large ...

I got some criticism last year, when I said “millions will die” as a result of climate change. And they said, “Oh, you’re being hysterical.” And I showed them the World Health Organization figures, and because of droughts, and agricultural disruption, and changes in diseases – disease patterns and epidemiology -- millions are already dying, or have died, as a result of changes in the climate …

This is not a … tempest in a teapot, that … if some people disregard the work of many thousands of scientists, that it is just, you know, a small matter. No, this is serious.

You also told that crowd in 2012, “The evidence for climate change is strong enough that we should be taking very bold and very expensive action, because the costs of not taking action will be even more expensive.”

Well, I hope I didn’t say “expensive action” … Most of the actions that we should be taking are real winners for us. I mean, if we in the United States produce real advances in energy efficiency technology, and improved means of generating and using energy, we stand to make a lot of money by selling this to the rest of the world. Better to be selling it than buying it. So investing in alternatives to fossil fuels need not be expensive. But if we don’t deal with climate change, the costs will be expensive, will be very costly … in lives and dollars …

I may have said that [“very expensive”] in answer to a question. Because, sure -- I mean, if we’re going to change the way we generate electricity, the way we heat our homes, the way we light our streets, and run our factories, that will require a lot of retooling. So in some narrow-minded sense, that’s expensive. But in the big scheme of things, this is … economic improvements that increase productivity, and really improve the standard of life …

You might call it expensive, or you might call it a bargain.

Have you seen real progress toward that kind of “very bold” action in the past couple years, and do you see any prospect for it happening this year?

Well, there’s no question that a number of energy technologies that were considered almost pie-in-the-sky, or too expensive to implement -- whether it’s solar, or wind, or geothermal energy, or whether it’s LED lighting -- those are now more than cost-competitive … In many, many situations, those are the ways to go.

So yeah, there have been real improvements … We have been making the mistake of using those improvements as an excuse for us to continue to burn more fossil fuels …

Instead of really embracing energy efficiencies, and finding ways to use less energy to get the same benefits to our lives, instead of doing that, we’re using still more. Instead of leaving the carbon in the ground, we’re spewing it into the atmosphere.

And we’re doing damage in a lot of ways with fracking, with the fracturing of shale to bring out the natural gas. We, it appears -- and this is not established yet, this is preliminary -- it appears that we are releasing a lot of methane into the atmosphere, which has a global greenhouse effect as great as, or greater than, carbon dioxide.

So yes, we’re making progress in a lot of particulars. But in the overall picture, no, we’re not.

Do you see any prospect for significant progress this year in Congress?

In Congress, I don’t see much hope for progress right now in much of any area. This is the least productive Congress in anybody’s memory, and that’s by design -- that’s what the leadership wants …

I remain hopeful -- I even expect -- that we will get good immigration reform legislation done this year. But that’s about the only area where I am willing to predict that we will accomplish something in this Congress. Not in energy, not in environment, not in education – any number of other areas.

In their 2012 town hall debate, Mitt Romney pledged to “fight for oil, coal and natural gas.” President Obama touted the fact that “we’re producing more coal,” and knocked Romney for having stood in front of a coal plant and “said, this plant kills.” Neither of them mentioned climate change. What does that tell you about the state of climate change politics?

Well, I mean, the president made a strong and fairly comprehensive statement last summer … He made it pretty clear that climate change requires strong action, and if Congress wasn’t going to do it, he was going to take the administrative steps he could -- that had to do with invoking the Clean Air Act, with putting limitations on coal-fired electric generation.

So, I mean, I think the president clearly is motivated to do a lot to address climate change … The administrative actions are not a substitute really for strong congressional action.

And it’s really quite, quite amazing how little congressional action there is, how effective the disinformation has been … There are moneyed interests that have spent an enormous amount of money sowing doubt.

It’s very much reminiscent of the behavior of the tobacco companies during the smoking and cancer debates. They took what was becoming overwhelming evidence … that smoking caused cancer, and they planted doubts in people‘s minds -- and through that, got a couple more decades of lucrative tobacco sales … until it became once again overwhelming in the public mind that smoking killed people …

[On] climate change, there’s been an enormous amount of money spent sowing doubt in people’s minds. So an awful lot of people nowadays say, “Well, climate change? I’m just not sure. Maybe it’s going on, but there’s so much uncertainty -- you know, scientists are so unsure. They’re on all sides of this issue.”

No, they’re not. Scientists aren’t unsure. I mean, sure you can find a few outliers … But scientists aren’t in doubt. The scientific consensus is strong. But the disinformation campaign has been surprisingly effective.

The Keystone Pipeline – last year you called it “all risk, no reward.” If that is approved by the administration, what will that mean for the environmental legacy of the president?

Well, there are a couple of problems -- big problems -- with the XL pipeline.

The first problem is that it just deepens our tie, our investment, in fossil fuels. This material in Canada -- you can’t really call it oil … it’s a sludge essentially -- is very heavy in carbon. Partly because of its very nature -- you know, it’s very carbonaceous – but also because it takes a lot of fuel to turn it into something that is useful for fuel.

So it is a climate poison. And we shouldn’t be doing anything to encourage its use …

One of the arguments is, “Well, if we don’t build the pipeline, the Canadians will get it to market somehow.” Well, OK, maybe they will. But I don’t think we should be abetting them in this.

The second thing … is this pipeline passes through the United States, where most of this fuel from Canada would be going to export from Texas ports … It is exempt from the oil spill insurance program, so that if there is a spill, it’s not even paid for. And we know there are spills; there have been spills of this very substance … spills that are environmentally damaging.

So that’s the risk, and there’s no gain. It’s to be sold overseas. We don’t even collect environmental insurance money for it …

Once the pipeline is built, the jobs are negligible … I’ll concede that there would be an appreciable number of construction jobs for a brief time. But that’s not worth the damage that we’re doing … the cost in lives and dollars.

You entered Congress in 1999; you’ll leave at the start of 2015. What are you going to tell your grandchildren or great-grandchildren about what Congress knew about climate change in that time, and what you did about it?

Good question …

Scientists are better than the general public at thinking statistically … If you understand these things, you understand that there is sufficient reason -- in fact, strong reason -- to take action to restrict the emission of greenhouse gases … There are good economic reasons to do so … We actually can make money by developing new technologies and changing the ways we produce and use energy … So there are a number of reasons for us to act, and really no good reason for us not to …

So it will be hard to explain to future generations, who will pay an even greater price than the current generation from climate change; it will be hard to explain to them the inaction of America and the U.S. Congress.

Do you have regrets about the way that you’ve approached this issue over the past several years?

Well, you know, the House passed a bill to put a price on carbon [in 2009]. It was not a bill that was exactly as I would have designed it from scratch, and I actually held out until the end -- to negotiate, in that bill, more funding for research and development in alternatives to fossil fuels.

And, despite the shortcomings of that bill, it would have been important. It would have been effective. And it’s too bad that it died in the Senate, that the Senate couldn’t get their action together. I don’t know what we in the House could have done differently or better there …

I have been sounding the alarm on this for, well, a couple of decades. You know, I’ve been intrigued by the science, climate science, for 50 years now … Ever since it became clear that this was headed in a dangerous and costly direction, I’ve been sounding the alarm. So, maybe I could have done more. I don’t know what that would be.

Shares