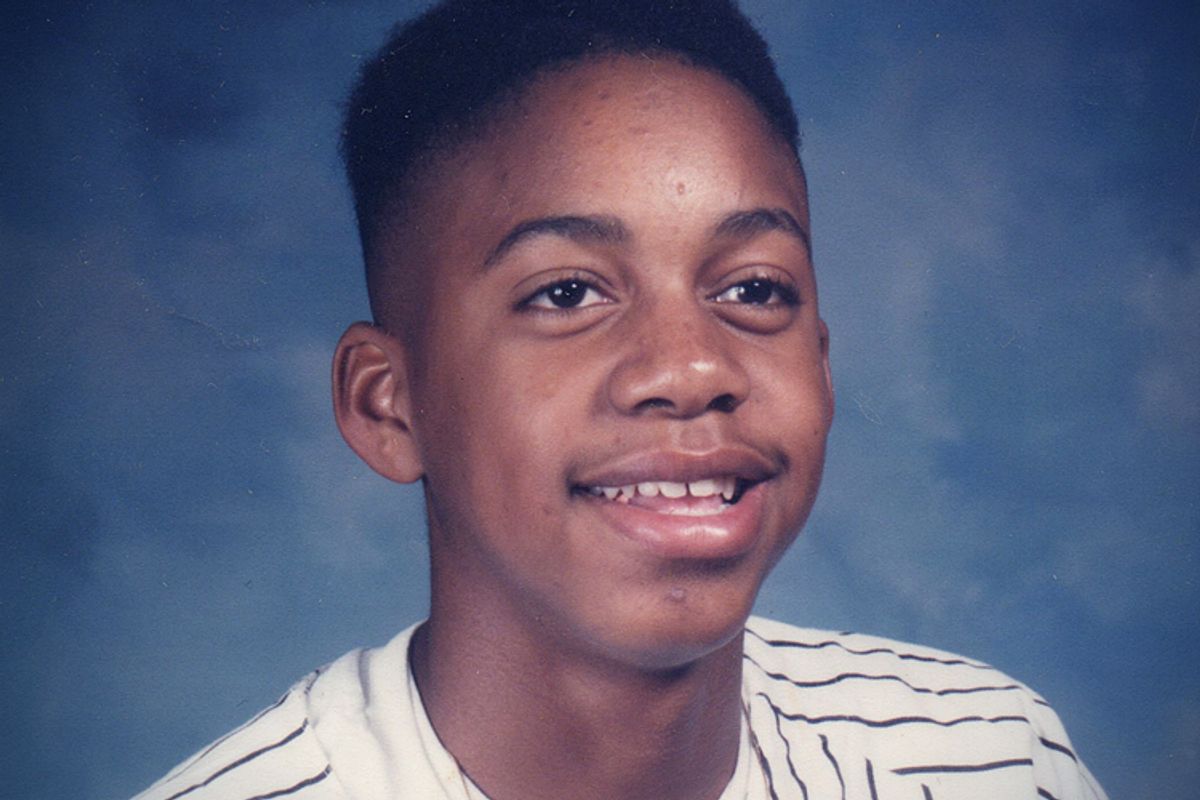

Weeks back I was social media surfing my brain cells into corpses when I happened upon a picture of a crew of young dudes from my hometown. Dudes who like me were born and raised in the mostly black snatches of Portland, Oregon, a city touted then and now in the media as the “whitest city in America.” All of the photographed were dressed in red gang gear, or “flamed up,” as we say. The guy who posted the picture tagged it with this (noted) run-on caption: “This is really f’d up 10 friends in 93 now only 5 remain sad but true… b.i.p [blood in peace] homies.”

Though I would only consider one of the photographed group a friend (he’s one of the living) I knew of the others, and though it’s sad that half of them, none of whom would be beyond their early 40s today, are deceased, let me keep it the realest with you folks: It isn’t if at all surprising. Such was our warlike era of pistols and pathos and misguided ethos and what seemed very little logos that began sometime around the late 1980s, right after the seminal ganglife movie "Colors" hit our dare-to-show-a-black-flick theater. Ours was an era fueled by NWA, who made gangster rap a marvel, an era that later found its most passionate spokesman in rap deity Tupac, who for all his uplifting, seemed dead set on inspiring a nation of the young, black and disenfranchised — i.e., us — to make Thug Life a way of life.

As for me, I never considered myself a thug or claimed a color, but as a small time/part time dope dealer who hawked soft and hard cocaine for most of my youth, I was close enough to the streets to have been a hash mark on either side of my city’s homicide count. One particular close call is ever-present for me.

It was dawn one summer morning, and I was hightailing it out of the house of a young woman who lived in one of those neighborhoods the wise would warn thou shalt not inhabit off hours, at least not without consequence. From a block or so away I saw a guy bicycling toward me in an all-black get up replete with black wool cap. By the time I saw who it was, an aspiring-toward-notorious gang member, I had the good sense to be worried. Word on the street was he and his buddies had attempted a home invasion of the house I lived in with my then girlfriend and her two kids, a plan thwarted, thank God, by a neighbor who threatened to call the police.

“I heard you was looking for me,” he said, confirming word had reached him that I knew he was in on the scheme, a truth that by our code (more on this code later) meant we had serious beef. He pulled out a pistol and aimed it at my bony chest and stared with what I suspected even then was the empty-eyed gaze of a human who would do anything. “Cuz, you looking for me?!”

I looked one way and then another, saw not a single potential witness in sight. I recalled the rumor I’d heard about him being hooked on sherm (PCP laced cigarettes and blunts that were the rage among gang members who “put in work”). Recalled stories of him shooting people just as easy as he breathed. I dropped my eyes, and shook my head. “Nah,” I said. “No, I'm not.”

“Yeah,” he said, his voice cranked, his pistol shaky. “Yeah, that’s what I thought. ‘Cause I'm a real killer!”

He was not, as we say, fatmouthing. If I told you his government name what you’d find if you cared to search is that he is now in a maximum security prison convicted of two murders, one that sent him to prison a year or so after our conflict, and one he committed while inside of a prison. And here’s an interesting fact: both victims were his former friends.

In fact, he and I could have been friends. Just a couple years prior we were skinny non-mustached teens who attended the same high school. We’d been enrolled in a class together, engaged in conversations, shared what I believed were genuine laughs. Like the crew in the photo, dude who pulled the pistol on me chose a color, but unlike them it was Crip blue. Bloods versus Crips. The murderers and the murdered. We were friends killing friends. We were family who on occasion killed family. Before my city became famous for "Portlandia" and white folks campaigning to “Keep Portland Weird,” there was what seemed a legion of young soldiers waging an inside war and the rest of us trying our loyal best not to get wounded.

What can I say about the whole sad business? My peers and I longed to make a life but couldn’t see the means beyond a sport or selling dope. We craved love but were loved to a dearth if at all. We ached for honor but had an ultra-skewed sense of what that was and how to earn it. Far too many forged atomic toughness, took up arms as panacea, let bullets prove their tensile strength.

For sure, similar symptoms of color-coded poverty were happening in cities all across the country, and no doubt many cities were hit harder stats-wise by the violence, but in the case of my city, those numbers mislead. Depending on which poll you cite, blacks have made up a whopping 3% to 5% of Portland’s population for decades, with most of them clustered in two quadrants. What that meant for melanin-blessed residents was this: When someone was robbed or stabbed or shot or beat or killed, there was a chance you knew the assailant and the victim and almost a sure bet that you were no more than a third person removed from both, e.g., the time in high school when the point guard on my hoop team, a guy I considered a homeboy, shot my cousin. Our communion was such that in aftermaths our allegiance was often confused. Our intimacies made most of our outcomes feel preordained.

And yet here I am with a pulse, free of the penal system, making a life three thousand miles from home.

How, I say to myself. How, self, did we avoid getting killed?

There were practical ways born of what I will claim as common sense. As in I had the sense to, in the midst of conflict, avoid aggravating a pistol-bearing foe. As in I stayed my ass out of the hot spots: i.e, the afterhours clubs, gambling shacks, parties with high counts of gangster patrons. As in I never dealt with a female who I knew to date gang members and/or anyone in the street life who had a rep for being grimy. As in I moved to a suburb and kept my address private from almost every human being in the universe. But what also kept me alive was recognizing the paradigm shift among us, that the time of “fighting a fair one” (a one-on-one fight with no weapons) was all but out the window. It was realizing that, while other dudes were risking life and soul to defend their sense of honor, I needed (call it punkish if you like) nuanced forms of courage. It was arriving at the immutable truth that many times the most gallant thing I could do was NOthing at all.

Ah, yes, deeds and tenets that kept me alive.

But what, I say to myself. What, self, kept us from killing?

To fathom the what, you must understand our code (told you I’d get back to it), which was some unquantifiable matrix: sense of right, sense of wrong, sense of worth, family, fame, faith, stature, allegiance, love, lust, legacy, justice, grace, trust, strength, esteem, freedom, family, hope, ownership, pride, pride, pride.

You must also understand the myriad ways that code could be breached, the circumstances under which you were or would be violated. If someone spoke ill of your name, fought you, tried to rob you or robbed you, harmed a loved one… you had been violated. If you wore the wrong color at the wrong time or in the wrong place, wandered into the wrong ’hood or onto the wrong street. If you fucked the wrong girl, flirted with the wrong girl, hung with the wrong dude, ignored the wrong thug, nudged the wrong fool minus a sorry, nudged the right fool with too meek of a sorry, sold to the wrong customer, shorted a customer, gave a customer too much for what they paid, had prime product, had a better dope connect, flashed your wares among the right ne’er-do-wells. If you gambled and lost too much, gambled and won too much, if you talked with the police or were suspected of such a serious crime... you might be considered in breach and violated. And if that happened, you should punish the offender(s). That punishment should be swift, stern, symbolic, should be a message to the near future, a warning, a DECLARATION. According to what was often a most subjective justice, that declaration could or should be lethal.

So why am I not a murderer when by that code once, twice, thrice or more I would’ve been just in the deed? For one, I didn’t, like so many of my peers, fall in love with a pistol; in fact I never carried one until I’d been robbed — twice. For two, I coveted the hope that I was not going to be a lifer, and since my days as a halfhearted hustler would expire, I had to avoid as best I could actions that would dictate a future of my grave unliking. Why else? Well, I could cite belief in a higher power, a deep religious calling, but folks, let me keep it 100 with you: The crux of why I’m not a killer has little if anything at all to do with God or morals or mercy or fear or any philosophy save the most simple survival math: I have yet to meet a man whose life was worth more than mine.

A couple months ago I was visiting my beloved Rose City and ended up at a shindig. Should’ve known what kind of set it was by the clique of dudes at the entrance flamed up and reeking of blunts, should’ve known when no sooner than I took a few paces inside, I heard a dude scream, “Blood, that’s on everything I love, he don’t want no problems.” No doubt, I should’ve heeded my smarter self and left lightspeed, but call me nostalgic cause instead I made my way to the bar and ordered a glass of wine (yes, wrong drink choice for the set). There I stood sipping Merlot, wearing nerd glasses and pants a tad too snug for the crowd, almost 20 years hence from any acute ballistic threat, watching a scene that featured plenty short skirts and plain-view tattoos, an ephemeral fisticuff or two, and no few goons stalking the crowd with a wicked scowl and their chest poked out. Sometime that night one such young thug bumped me so hard it could have only been a taunt and swaggered off like the dead and jailed of my yesteryears. So it goes: I dabbed the spilled wine from my sleeve with napkins, tracked the culprit’s route, and began to compute. Survival. Math. Trust and believe you learn, or else, when forevermore the answer equals life or death.

Shares