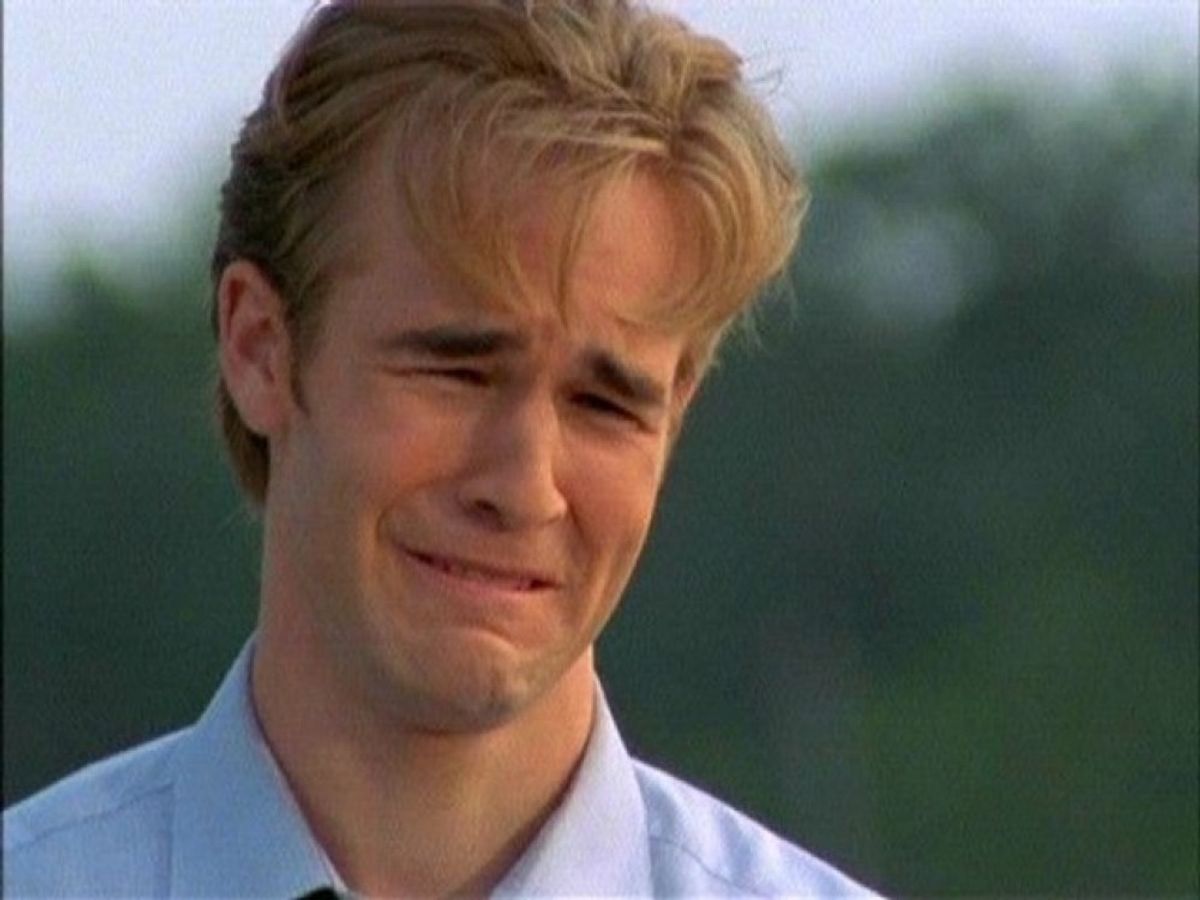

Loser! You messed this up again! You should have known better!

Sound familiar?

It’s that know-it-all, bullying, mean-spirited committee in your head. Don’t you wish they would just shut up already?

We all have voices inside our heads commenting on our moment-to-moment experiences, the quality of our past decisions, mistakes we could have avoided, and what we should have done differently. For some people, these voices are really mean and make a bad situation infinitely worse. Rather than empathize with our suffering, they criticize, disparage and beat us down even more. The voices are often very salient, have a familiar ring to them and convey an emotional urgency that demands our attention. These voices are automatic, fear-based “rules for living” that act like inner bullies, keeping us stuck in the same old cycles and hampering our spontaneous enjoyment of life and our ability to live and love freely.

Some psychologists believe these are residues of childhood experiences—automatic patterns of neural firing stored in our brains that are dissociated from the memory of the events they are trying to protect us from. While having fear-based self-protective and self-disciplining rules probably made sense and helped us to survive when we were helpless kids at the mercy of our parents’ moods, whims and psychological conflicts, they may no longer be appropriate to our lives as adults. As adults, we have more ability to walk away from unhealthy situations and make conscious choices about our lives and relationships based on our own feelings, needs and interests. Yet, in many cases, we’re so used to living by these rules we don’t even notice or question them. We unconsciously distort our view of things so they seem to be necessary and true. Like prisoners with Stockholm Syndrome, we have bonded with our captors.

If left unchecked, the committees in our heads will take charge of our lives and keep us stuck in mental and behavioral prisons of our own making. Like typical abusers, they scare us into believing that the outside world is dangerous and that we need to obey their rules for living in order to survive and avoid pain. By following (or rigidly disobeying) these rules, we don’t allow ourselves to adapt our responses to experiences as they unfold. Our behavior and emotional responses become more a reflection of yesterday’s reality than what is happening today. And we never seem to escape our dysfunctional childhoods.

The Schema Therapy Approach

Psychologist Jeffrey Young and his colleagues call these rigid rules of living and views of the world made by the committee in our heads “schemas.” Based on our earliest experiences with caregivers, schemas contain information about our own abilities to survive independently, how others will treat us, what outcomes we deserve in life, and how safe or dangerous the world is. They are also responsible for derailing intimate relationships.

Young suggests that schemas limit our lives and relationships in several ways:

- We behave in ways that maintain them.

- We interpret our experiences in ways that make them seem true, even if they really aren’t.

- In efforts to avoid pain, we restrict our lives so we never get to test them out

- We sometimes overcompensate and act in just as rigid, oppositional ways that interfere with our relationships.

A woman we will call Diana has a schema of “Abandonment.” When she was five years old, her father ran off with his secretary and disappeared from her life, not returning until she was a teenager. The pain of being abandoned was so devastating for young Diana that some part of her brain determined she would live her life in such a way as to never again feel this amount of pain. Also, as many children do, she felt deep down that she was to blame: she wasn’t lovable enough, or else her father would have stuck around; a type of "Defectiveness” schema.

Once Diana developed this schema, she became very sensitive to rejection, seeing the normal ups and downs of children’s friendships and teenage dating as further proof that she was unlovable and her destiny was to be abandoned. She also tried desperately to cover up for her perceived inadequacies by focusing on pleasing her romantic partners and making them need her so much that they would never leave her. She felt a special chemistry for distant, commitment-phobic men. When she attracted a partner who was open and authentic, she became so controlling, insecure and needy that, tired of not being believed or trusted, he eventually gave up on the relationship.

Diana’s unspoken rule was that it was not safe to trust intimate partners and let relationships naturally unfold; she believed that if she relaxed her vigilance for a moment, her partner would leave. In an effort to rebel against her schema, she also acted in ways that were opposite to how she felt; encouraging her partner to stay after work to hang out with his friends, in an attempt to convince herself (and him) that she was ultra-independent. This led to chronic anger and dissatisfaction with her partner.

Diana did not understand her own role in this cycle. Diana (and her partner) needed to understand how her schemas resulted in ways of relating to herself and others that are repetitive, automatic, rigid, and dysfunctional. By acknowledging and connecting with her unresolved fears and unmet needs, Diana could become more flexible and allow her partner more freedom without feeling so threatened.

The schema concept helps us understand how early childhood events continue to influence adult relationships and mental health issues, that we need to recognize their influence and (with professional help, if necessary), begin to free ourselves.

Six Things You Can Do Right Now

The tools and tips below will help you begin to identify your core schemas and take some corrective actions.

-

If you had an abusive childhood, early loss or trauma, or grew up with addicted or mentally ill parents, think about whether your patterns match one of the following schemas:

- Mistrust and abuse: Not trusting others to genuinely care for you. Feeling like a victim or choosing abusive partners. Acting in untrustworthy ways.

- Emotional deprivation: Feeling like your own emotional needs are not valued or met by others. Not speaking up or voicing your own needs.

- Abandonment: Feeling like others will leave you or won’t be there when you most need them.

-

In close relationships, think about your partner’s background, beliefs and behaviors to see whether they fit into one of the schema patterns identified here. Think about the times when your communication gets derailed and you both get angry or defensive. What schemas may each of you be bringing to the table and how may they be setting each other off. For example, a partner who has an Entitlement schema may act in needy and demanding ways that trigger the partner with an Emotional Deprivation schema to feel uncared for.

-

Pay attention to when you or your partner are getting triggered. You may notice feelings of anger or helplessness, thoughts that contain the words “always” or “never,” and feelings of tension or discomfort in your body. You may feel reactive and tempted to withdraw or say something impulsively.

-

Practice the STOP technique when you are triggered during a conversation with your partner. This is a practice from the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction course developed by John Kabat-Zinn. STOP what you are doing, TAKE a breath, OBSERVE what you are doing, thinking, feeling and what your partner is doing, thinking, feeling. Think about whether your schema is calling the shots and if you would like to change tracks. Then PROCEED with a more mindful response.

-

At a time when you are both calm, sit down with your partner and try to figure out the cycle that happens when both you and your partner get reactive to your schemas. Decide how to communicate that this is happening in the moment and call a break.

-

Train yourself in the skill of cognitive flexibility. Deliberately think about other ways to interpret your partner’s behavior that are not consistent with your schema? Perhaps he is withdrawn because he had a hard day at work. Are you personalizing things too much?

Shares