On April 1, 1994, Kurt Cobain jumped a fence at Exodus Recovery Center in Los Angeles, purchased a plane ticket to Seattle, and disappeared. On April 5, he retreated to the garden apartment of his Seattle mansion, where he took his own life. On the morning of April 8, his body was discovered by an electrician. By the afternoon of April 8, his suicide was global news, with millions of fans around the world mourning the loss.

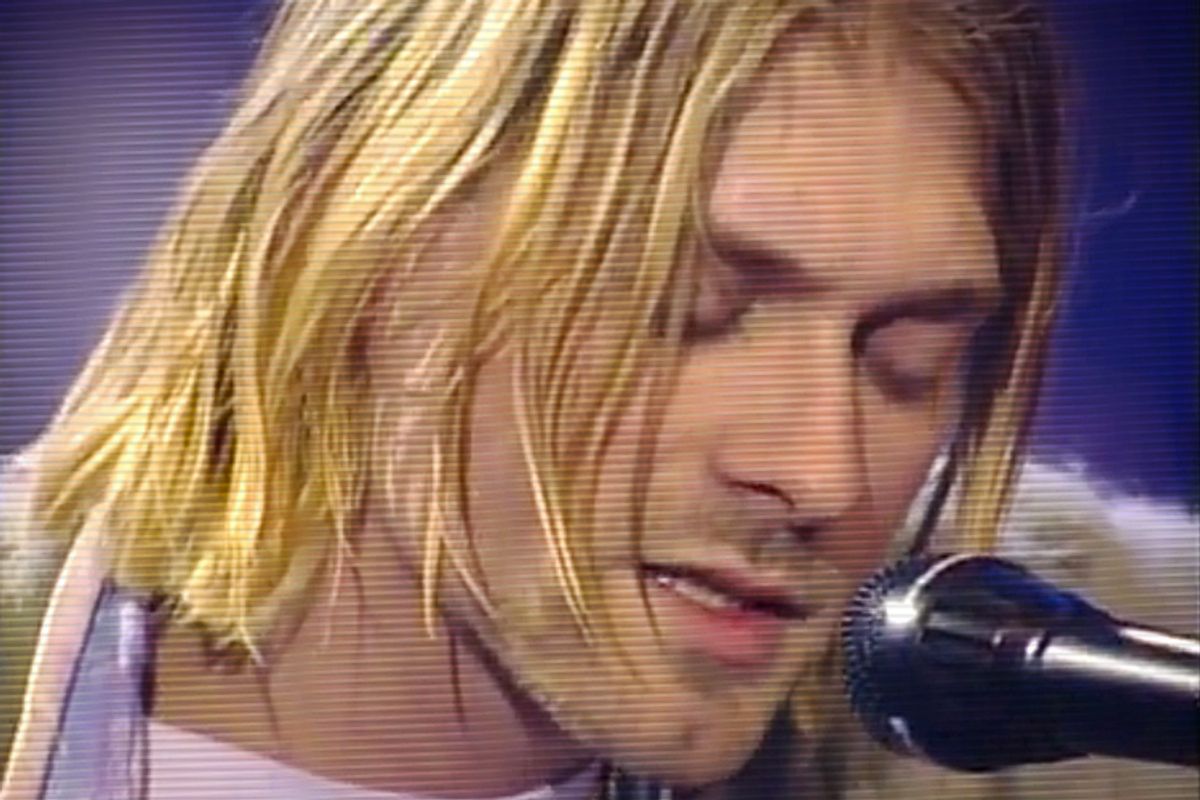

Twenty years later, Cobain may be more renowned for his gruesome death than for the music he made with Nirvana. In life he brought the underground into the mainstream, not only dispelling the frivolous hair metal of the ’80s but introducing so-called “grunge” music to listeners well beyond the Seattle city limits. In death, however, he capped a movement that had upended the pop landscape, lent even more credence to his self-reckoning lyrics and turned him into a rock and roll icon on par with Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin.

It’s impossible to calculate the influence Cobain has had, for better or for worse, on popular culture. That’s what Charles R. Cross, who was working as the editor-in-chief at the Seattle alt-weekly The Rocket when Cobain died, addresses in his new book, “Here We Are Now: The Lasting Impact of Kurt Cobain.” Cross is perhaps the leading expert on Nirvana, having written several books and articles on the band, and “Here We Are Now” reads like a lengthy epilogue to his definitive 2001 biography of Cobain, “Heavier Than Heaven.” Surveying the world Cobain left behind, this slim book examines how he changed not just music, but fashion, politics, addiction treatment and suicide prevention.

Cross is enough of a realist not to romanticize or idolize his subject, not to tease out the endless conditions and consequences of his life. As a result, his body of work on Cobain humanizes the rock hero and presents him with all his flaws and contradiction and genius and tragedy intact. “There are so many what-ifs in the story of a man who dies young and tragically,” Cross observes. “There are no answers, no matter how many hours you spend pondering, no matter how long you dream. Events of history don’t change just because you wonder about them.”

On the eve of the anniversary of Cobain’s suicide, Cross spoke with Salon from his home in Seattle, where he elaborated on the musician as publishing phenomenon, local hero and cautionary tale.

You’ve written extensively about Nirvana, and in addition to "Here We Are Now," you have a chapter in the new "Nirvana: The Illustrated History." What makes Kurt Cobain such a compelling subject?

I’ve written a bio and at least two other books on him, depending on how you add it all up, and I still don’t feel like I completely understand everything about him. He was a fascinating figure. You can’t explain him away. For such a short life — really only three years of fame — he did so much and created a body of work that can’t be easily explained. There has never been anyone in rock before or since quite like Kurt Cobain. I write in the book that he was the last rock star, and there are some people who take issue with that. There are definitely other stars in rock, but there hasn’t been anyone with the combination of Kurt’s songwriting talent and his voice. And by voice, I don’t mean vocal talent. I mean you got a strong sense that you were hearing him sing directly to you.

"Heavier Than Heaven" was one of the first real bestsellers about Cobain, one of the first titles to capture the scope of his life. Was it difficult convincing a publisher that he was a viable subject for that kind of biography?

With "Heavier Than Heaven," I felt I had a responsibility. There were a couple of books written about Kurt that frankly I thought were really poor and did not tell the story as I had witnessed it, and I felt he deserved a serious biography that didn’t deal with him as a celebrity but as a human being. I didn’t tackle the subject because I thought it was going to be commercially successful. In fact, it was just the opposite. This was not a book publishers were clamoring for. I had to argue with people in the industry that he was a legitimate topic. When we were discussing promotions for the book, I specifically remember the director of publicity for my publisher telling me that he didn’t think anyone’s going to want to hear about Kurt Cobain. But the book became a success, and I hope it played some role in shifting the perception of Kurt.

"Heavier Than Heaven" was translated into several languages and sold well around the world. What makes him so popular outside of America?

There is an immense international audience. Nirvana were always more popular in the U.K. than they were in the U.S., proportionally. And they’ve definitely been popular in South America, especially in Brazil. To those people outside of the U.S., Kurt doesn’t just represent music. He in some ways represents American rock and roll. He’s an ambassador for an entire culture. I’m not sure President Clinton, who was in office when Kurt died, would have appointed him ambassador to any of these countries, but he represents an entire era of American culture to many of them. There are many people who learn English by learning the lyrics to “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” That’s probably not what English as a Second Language instructors would teach — an albino, a mosquito, my libido. But that’s an entrée into our language for many people. I think that shows the enduring power of these lyrics.

One of the best chapters in the book is on Aberdeen’s attempts to embrace his legacy and erect a memorial of some sort. That’s an aspect of Cobain’s story that isn’t talked about very much, but really crystallizes some of the issues around his life and death.

The book went to press six months ago, but there have been five or six things that have happened since then that could have been chapters in this book. Obviously there’s that Dutch beer commercial, and then the town of Aberdeen attempts to honor Kurt but fucked it up royally. They had this ridiculous event where they unveiled a statue of Kurt crying. And then they sing “Happy Birthday” to it. It reads like something that should be in the book. Kurt had a troubled relationship with his hometown that keeps playing out again and again, yet even to much of the media, Aberdeen just doesn’t exist. One thing that people have been surprised by — when they read the book, they go, What? Kurt only lived in Seattle for 18 months? Yes. It wasn’t even 18 months. He had an official address for 18 months, but he was on tour for most of that time. So, for a guy so closely associated with Seattle, he actually didn’t spend too much time there. It was something he aspired to. Kurt was such a small-town boy, and when he first came to Seattle for Nirvana’s first gig there, he was so afraid he was going to get mugged that they drove around all day in their car. They never stopped. Even in 1988, that’s just absurd. He probably saw one or two winos and completely freaked out.

In that Aberdeen chapter, you write about Tori Kovach, who cleared the land around the Young Street Bridge and created a DIY park in Kurt’s honor. At first it seems like a perfect way to memorialize him, but it changes the landscape that Kurt knew as a private sanctuary and turns it into something public. It seems almost impossible to fashion a reasonable and appropriate tribute to him.

It is very difficult. Kurt wanted attention, and at the same time he wanted to pretend that he didn’t. Would he have wanted to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? In all likelihood, absolutely. Would he have pretended that he didn’t? Absolutely. But the band struggled with its popularity and the monster it became, so it’s very hard to figure out how to memorialize Kurt. My idea for Aberdeen, which I presented when I gave a reading there recently, was to simply create a brochure and put up some plaques in front of some of the places where Kurt lived. That would give some direction to tourists in the city. But Aberdeen is still a dangerous city. At the reading we went to the neighborhood where Kurt grew up, and it’s very late, and I’m there with my 14-year-old son. I have to tell you, I’m a grown man who has pretty good street smarts, and I’m wondering if we should even be walking down this street this time of night. Honestly, I have no idea how Aberdeen should honor Kurt. I certainly know that they have done a poor job of it so far.

Another highlight of the book is the chapter on Kurt’s impact on addiction treatment and suicide prevention.

If this book is thought to break any news, then that’s the news. I was surprised to learn that the suicide rate went down after his death. I was under the belief that there had been an uptick in suicides. There were so many graphic details in the press, and all of it seemed really horrible at the time — too many details, too much information. But I learned that ultimately made people less likely to commit a copycat suicide. I was well aware of Marilyn Monroe’s suicide, but I didn’t know that she took her life in a way that people could romanticize. The way Kurt did it was horrible and violent, and that made people much less likely to emulate him. So there were fewer suicides right after Kurt’s death. The sad truth, however, is that the rate has shifted and is higher than ever in America.

The reasons that people kill themselves are far more complicated than the fact that they like a certain band or celebrity. There are suicidologists — what a weird profession! — who have written about this topic long before Kurt came along, and what they found was that kids who sang along to songs about suicide were less likely to actually commit suicide. No one knows why exactly, but the theory is that if you grow up loving music, the lyrics somehow help you live your life with more meaning. The lyrics may be sad, but they might actually help people process their feelings instead of acting them out. That’s a fascinating way to look at it.

How has your relationship with the music changed over the years? Has writing so much about Kurt altered the way you hear and process his music?

It still means the same things it meant to me 20 years ago. It still takes me away from where I am. At the same time, I listen to it with an investigator’s eye. I appreciate it from a purely artistic standpoint, but I’m also listening to it like Sherlock Holmes. Where did this line come from? Where did that riff originate? Even after writing "Heavier Than Heaven" and this new book, I still find new pieces of the puzzle. When I was in Aberdeen, somebody came up to me after the reading and said they had found this piece from a city directory from the 1940s about the Morck Hotel, which is now abandoned. Kurt spent time in that hotel as a homeless teen, and its slogan just happened to be “Come as you are.” I still haven’t found a picture of the interior that shows it, but I presume it must have said that on one of the walls inside. Nobody’s ever mentioned this before. I don’t even think Krist Novoselic knows that. Whether Kurt borrowed that line or it was just rooted in his subconscious, I don’t know.

For the last couple of years, my main entrée into Nirvana has been my 14-year-old son, who grew up in a house where there were stacks of various foreign editions of "Heavier Than Heaven" on the bookshelf. But I never pushed Nirvana on him, and I rarely played it around him, so it’s not like he has to love this stuff just because he’s my kid. He began playing guitar a couple of years ago. I’m not his teacher, though. But it was really surprising to have my kid come home and start picking out the notes of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” So I’ve been able to get a whole new appreciation for Nirvana to hear what it means to someone just discovering it.

Shares