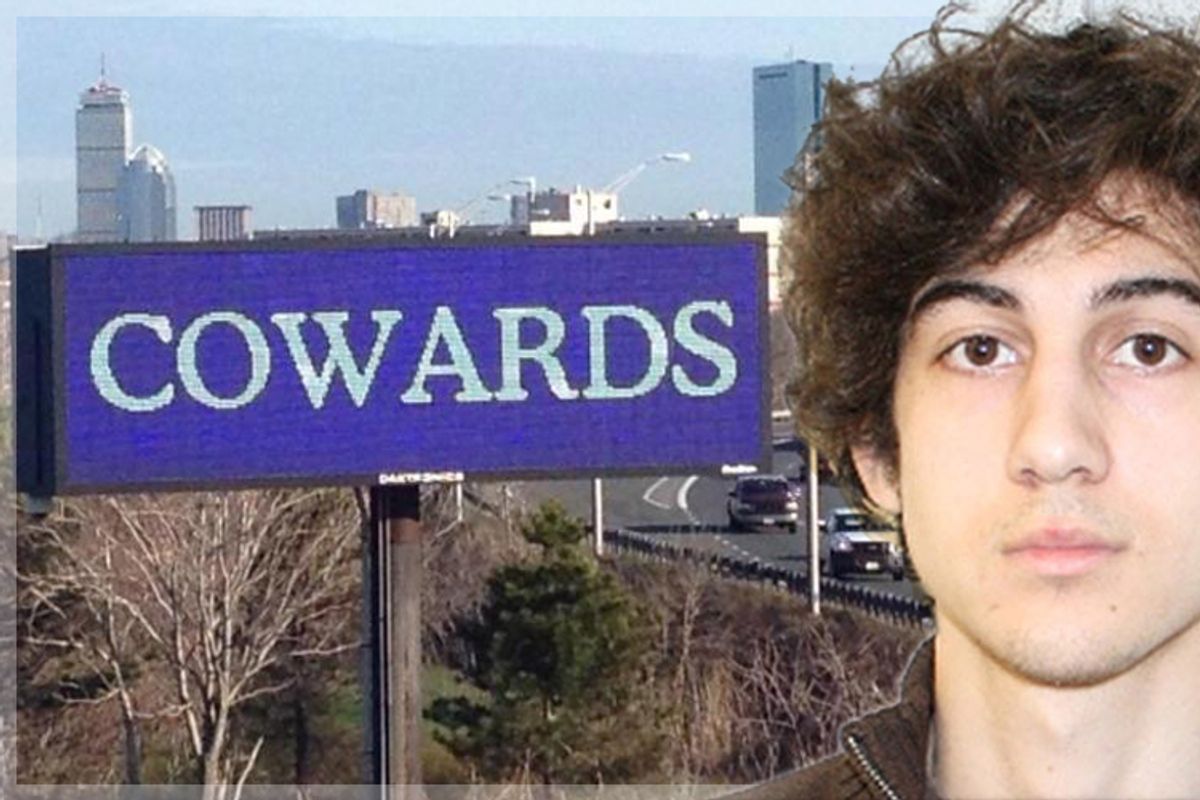

Before any of us knew who they were or why they had done it or what they might do next, one thing seemed certain: The Boston Marathon bombers were cowards. Overlooking the expressway leading into the city, an electronic billboard flashed the message the day after the bombing, complete with a hashtag.

It felt good to see and say this, a bitter and righteous rebuke to those who would terrorize us. The billboard was courtesy of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 103, and everyone from President Obama to Gov. Deval Patrick to Boston Red Sox management echoed the sentiment. Something similar had happened a dozen years earlier, when President George W. Bush and many others called the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks cowardly. Our habit of using "coward" in this way is understandable, but it comes at a cost.

Calling terrorists cowards felt good for a few reasons. First, the word satisfied the need to lay offenders low with the nastiest possible term of abuse. There is nothing worse than a terrorist, goes the logic, and, as long and enduring tradition has it, there is nothing worse than a coward. The cowardly begin the Book of Revelation’s list of those damned to burn forever in a lake of fire, and they are the most despicable souls in Dante's "Inferno." Urbandictionary.com defines coward as "the most insulting word known to man."

Calling the terrorists “cowards” also felt good for the perhaps childish reason that the terrorists had used the term first. The idea of American cowardice runs through the rhetoric of violent jihad. In his 1996 fatwa, for example, Osama bin Laden wrote that its cowardly withdrawals from Vietnam, Beirut and Somalia ("your most disgraceful case") had shown that, if attacked, the U.S. would abandon its commitments.

Calling the terrorists “cowards” was also strangely comforting. Three days after the marathon bombing, when the suspects were identified and came out of hiding, armed and murderous, my family heard the sirens and helicopters. That night they allegedly killed an MIT police officer just down the road from us, then hijacked a car and engaged in a deadly firefight with the police. It was a scary time, but as we followed the orders to “shelter in place” — a phrase we’d never heard before — it was reassuring to think of the suspects as cowardly. If they were cowards, then they were scared too — vulnerable, weak. And thinking them weak made another new phrase — “Boston Strong” — more convincingly true.

It felt good to call the terrorists cowards. Whether it was accurate to do so was another matter. You might recall the controversy over the labeling of the 9/11 attackers in this way. Bill Maher, among others, noted that the men who hijacked planes and flew them into buildings were not, strictly speaking, cowards. Indeed, he said, Americans “have been the cowards, lobbing cruise missiles from 2,000 miles away.” This was on "Politically Incorrect" less than a week after the attacks — not a time for speaking strictly. The show soon went off the air.

Maher had a point. As someone who's been working on a book about cowardice for over a decade, I know that it's a slippery concept, but also that classical, linguistic and military tradition define it pretty clearly as the failure, born of excessive fear, to do one's duty. Such a definition does not seem to apply to the 9/11 terrorists, who were doing what they saw as their duty, and doing it despite their fears of death (no matter what they might have thought about the paradise that awaited them in the next world).

Yet in saying that the Americans were cowardly for using missiles, Maher was misusing the term the same way those who called the terrorists cowardly were. There was nothing new in such misusage. In 1926 the linguist H.W. Fowler lamented "that the identification of coward & bully has gone so far in the popular consciousness that persons and acts in which no trace of fear is to be found are often called coward(ly) merely because advantage has been taken of superior strength or position." It is for this same reason the term is sometimes used for serial killers, rapists and pedophiles. And if enough people misuse a term for long enough, the misusage becomes usage. That's how language works.

But the semantic shift impoverishes our ethical vocabulary. In reserving cowardice for terrorists and predatory criminals, we make it seem a rare and monstrous thing. The flashing billboard --#COWARDS -- applies to them, but not to us, and that keeps us from asking questions that a more rigorous understanding of cowardice provokes. Were we right to call the terrorists cowards, or does withdrawal from Iraq and Afghanistan prove bin Laden's point about American cowardice, a repetition of the pattern established in Somalia, Beirut or Vietnam? Can this pattern be traced back further, to a history of fickle American foreign policy, a lack of steadfastness characteristic of a commercial democracy largely isolated from the rest of the world, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed long ago? Is the American obsession with security itself cowardly, leading us to shelter in place too readily, to surrender privacies to the NSA, to lead the world in incarceration?

#COWARDS also distracts us from thinking about the idea in a more profound and disturbingly personal way -- what Mark Twain called “man’s commonest weakness, his aversion to being unpleasantly conspicuous, pointed at, shunned, as being on the unpopular side. Its other name is Moral Cowardice, and is the supreme feature of the make-up of 9,999 men in the 10,000.”

The classic depiction of moral cowards occurs very early in Dante's "Inferno." Past the sign that says to abandon all hope, just through the gate of hell, but before crossing the Acheron to hell proper, Dante encounters a horde of moaning souls. His guide Virgil doesn't want to talk about them -- nobody ever wants to talk about cowardice, it seems (that's another thing I've learned working on the subject) -- but he does tell Dante that these are the abject wretches who lived with neither disgrace nor praise. They are the neutrals, nonparticipants, spectators. Among them are those angels who stayed on the sidelines when God and Satan did battle. Paradise won’t have such shades tainting its beauty, and the Inferno is barred lest the condemned have someone to glory over. This is what makes these souls the most despicable -- in the root sense of being looked-down-upon -- in the "Inferno." Not having acted or chosen, they never truly lived or died, and so are condemned forever to hell’s squalid lobby, stung by wasps and flies, chasing a banner that says nothing.

Martin Luther King evoked this scene when he lamented Americans’ apathy about their country's involvement in the Vietnam War. King said he “agreed with Dante that the hottest place in hell is reserved for those who in a period of moral crisis maintain their neutrality. There comes a time when silence becomes betrayal.” Dante actually makes no mention of the temperature of this particular spot in the "Inferno," nor, as we have seen, are the neutrals actually in hell. But King’s point is clear. Those who played it cool in life would ultimately catch heat.

One way to play it cool is through humor, "the most engaging form of cowardice," as Robert Frost put it. Irony, the characteristic humor of our time, has also been described as cowardly, driven, as Jedediah Purdy argued in 1999, by fears “of betrayal, disappointment, and humiliation, and a suspicion that believing, hoping, or caring too much will open us to these.” Those who give in to such fears refuse to commit to anything, except detachment.

I would not want to forgo irony altogether, though, for it can be a way of dealing with a stupid, brutal world that sometimes seems to have all the guns and numbers. Besides, irony’s opposite, absolute earnestness, can be morally cowardly too, when the true believer abjectly stays the course -- often because he fears that not staying the course would be cowardly. The 9/11 terrorists were sure that Americans were cowardly and that to turn from battle against them would be cowardly too. The U.S. government’s response reflected a similar feeling: The terrorist acts were cowardly, and such cowardice meant that the terrorists could be subdued if they were attacked — and it would be cowardly not to attack. An article in Inspire, an online publication of al-Qaida’s Yemen affiliate, asked sarcastically if Muslim Americans are “proud of associating themselves with a nation that continues to maim and kill the ummah [Muslim peoples] around the world both directly and indirectly? ... Or are they proud of being American because being one welcomes cowardice and hiding one’s head under the sand while the real problems exasperate throughout the Muslim lands?” The inaugural issue of this same magazine, among the favored online reading of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the older of the two marathon bombing brothers, featured an article titled "How to Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom."

But it is possible to have the cowardice of one’s convictions. Fundamentalism of any kind runs the risk of cowardice when it fearfully refuses to consider complications that may bring a salutary tentativeness to one’s conduct. In this sense, the Boston Marathon bombers can indeed be called cowardly, guilty of what Olivier Roy calls the “holy ignorance” of those who fail to understand the fullness — the complexity and nuance — of their own theology and culture, not to mention the precious price their violence exacts.

So maybe the billboard has something to teach us after all. The terrorists should have known better, and so should we know better. Confucius may have been wrong to say that “to know what is right and not to do it is the worst cowardice,” for it may be worse not to know, not even to try to know. Such cowardice characterized those in Nazi Germany who, as Primo Levi put it, “had the possibility of knowing everything" about the genocide happening around them "but chose the more prudent path of keeping their eyes and ears (and above all their mouths) well shut.” It may characterize us. The cowardice of past ages is relatively easy to see, but what will future generations see in our time, what duties did we fearfully shirk, and in so doing compromise our principles, and bring harm to others, the planet, our descendants? And this is not to mention our more personal cowardices, seemingly invisible to us now but threatening to haunt our deathbed recollections — the times we gave in to our fear, as Twain put it, of "being unpleasantly conspicuous."

Yet thinking about cowardice can help us overcome cowardice. In studying moral blind spots, the way human beings fail to see things they would rather not see, psychologists have noted how good we are at keeping ourselves unaware of inconvenient or threatening information, and how, when it comes time to choose and act, desire trumps duty. We are good at not “acquiring information that would make vague fears specific enough to require decisive action,” as one psychiatrist put it, and good at disregarding the demands of such fearful information that we do acquire. Our ability to anesthetize ourselves is so powerful that just being aware of the ways we deceive ourselves is not enough to prevent self-deception, nor will all the good intentions in the world suffice to make us actually do the right thing. To “change the underlying dynamics,” Robert Trivers writes in "The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life," “we need much deeper confrontations with ourselves and our inadequacies, ones often drenched in tears and humility.” The idea of cowardice, properly understood, can push us toward such deeper confrontations. It is a dangerous, harmful idea, but it’s a bracing one too.

Dante is amazed at how many cowardly souls there are: “never did I think that death could have undone so many.” T.S. Eliot took up the line in "The Waste Land":

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Such are the main denizens in Eliot's vision of modern life -- "hollow men," he calls them elsewhere, "stuffed men" -- shuffling through life, refusing to look at the world beyond their toes. Though perhaps now we fix our eyes on our smartphones.

One critic of the “ante-Inferno” argues that having a sin so common it would apply to all mankind makes this particular part of Dante’s vision untenable. How could a vestibule possibly hold such multitudes? But maybe it is all too tenable. Maybe the numbers clinch the case.

Shares