Frank Rotondo is not pleased. He's the executive director of the Georgia Association of Chiefs of Police, and he's strongly opposed to the so-called Guns Everywhere Bill signed into law by Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal on Wednesday. “Police officers do not want more people carrying guns on the street,” said Rotondo, “particularly police officers in inner city areas.”

While grass-roots mobilization and legislative intervention have trimmed back some of the more extreme provisions, such as allowing guns onto college campuses, the law significantly expands the area inside Georgia where guns may be legally taken — most notably into bars, churches and schools — and lessens the penalties for taking them some places where they're still forbidden. Tellingly, former congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords’ organization, Americans for Responsible Solutions, calls it “the most extreme gun bill in America.”

There are some nuances: Guns may be taken into bars, but bar owners may specifically prohibit them, and they may only be brought into churches that specifically allow them. All this has led some to criticize the “guns everywhere” label. But even if intense activism has turned back some of the worst aspects of the bill, “guns everywhere” remains the basic logic behind the bill, and accurately reflects the mind-set pushing it forward, which sees guns as the ultimate source of safety, and protection — regardless of who actually gets hurt, or killed.

If you think I'm exaggerating, consider this rationale from Georgia state Rep. Rick Jasperse, who introduced the bill: “When we limit a Georgian’s ability to carry a weapon — to defend themselves — we’re empowering the bad guys.” It's a cleaned-up version of National Rifle Association spokesman Wayne LaPierre's claim, “The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” but it's equally mistaken, as law enforcement professionals like Rotondo are, tragically, all too aware of. Academic researchers know it, too, as the “more guns/less crime” argument has been thoroughly debunked. Common sense rebels as well: If guns made us safe, the U.S. would be one of the safest nations on earth, rather than one of the least safe, when it comes to deaths and injuries from gun violence.

But there's an even deeper problem with this so-called logic, which goes to the very heart of the NRA's political worldview: their mistaken views about the relationship between gun-ownership and the foundations of a free and secure society. Ultimately, it's the power of this worldview, and its dubious claim to represent America, that needs to be challenged and thoroughly discredited, if we are ever to really secure our freedoms, as well as our lives.

According to the NRA's logic, the right to bear arms is a fundamental right, on which all other rights depend. It is the basis for all our freedoms. But according to John Locke, the most central and venerated figure in rights-based political theory, it's precisely the opposite: Our civil society is based on the inability of guns to protect our freedom and security.

Although Ayn Rand's popularity has skyrocketed recently, libertarians have traditionally tried to claim Locke as one of their own, because his social contract theory begins with a “state of nature” in which individuals have absolute God-given rights. But Locke's whole point is not the superiority of this state, but the exact opposite — its obvious failure. And it's from this failure that the foundations of civil society are laid.

In his Second Treatise of Civil Government, Locke not only explains this failure, but also how readily and universally that failure is perceived. In Section 123, he first puts the question:

If man in the state of nature be so free, as has been said; if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest, and subject to no body, why will he part with his freedom? why will he give up this empire, and subject himself to the dominion and controul of any other power?

And then answers it decisively:

To which it is obvious to answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain, and constantly exposed to the invasion of others: for all being kings as much as he, every man his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of equity and justice, the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, very unsecure. This makes him willing to quit a condition, which, however free, is full of fears and continual dangers: and it is not without reason, that he seeks out, and is willing to join in society with others, who are already united, or have a mind to unite, for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name, property.

It's ironic that libertarian conservatives, who care so much about property, should be so deeply ignorant about its crucial role in motivating the formation of civil society, according to the very man they love to mistakenly cite as such a high authority endorsing their views.

But their ignorance of Locke goes even deeper than that, since they misunderstand the whole purpose of his philosophy, as well as its place in history. Locke's aim was never to valorize a pure and mythical original state of being, but rather to justify the existing order of civil society, without recourse to either theocratic or other authoritarian arguments. Locke's Second Thesis — still widely read today — followed his First Thesis, an extended refutation of a theocratic justification, broadly sympathetic with the “divine right of kings.”

But Locke also less directly attacked the authoritarian argument of Hobbes' "Leviathan," primarily by envisioning a very different, much less paranoid version of the state of nature. Hobbes famously thought the state of nature was a “war of each against all,” whereas Locke saw it as a state governed by moral principles, but not law. In Locke's view, war was emphatically not the universal state, but just as emphatically was a state that men could blunder into — and once blundered into, there was no means of escape. Only prevention provided a way out, and that prevention was the social contract.

What all this shows is that Locke's views of government, rights and property are all engaged with a realistic, but fundamentally moral, pro-social view of human nature: a strikingly liberal view of who and what we are: basically good, but flawed individuals, who need one another to fully thrive. The failure of individual force to secure human happiness is not a tragedy for Locke. It is simply an inescapable fact.

The NRA, of course, believes the exact opposite of this — or at least preaches it. (As a nearly total tool of the gun industry, the only thing it really believes in is selling more guns.) And that is why the NRA today is such a crucial linchpin in the conservative movement. In their view, the closer to the state of nature, the better. Society itself is evil (the collective vs. the individual), and government the greatest evil of all — even worse than “a bad man with a gun,” who, after all, can be easily gotten rid of by “a good man with a gun.” Government itself is a good deal harder to get rid of.

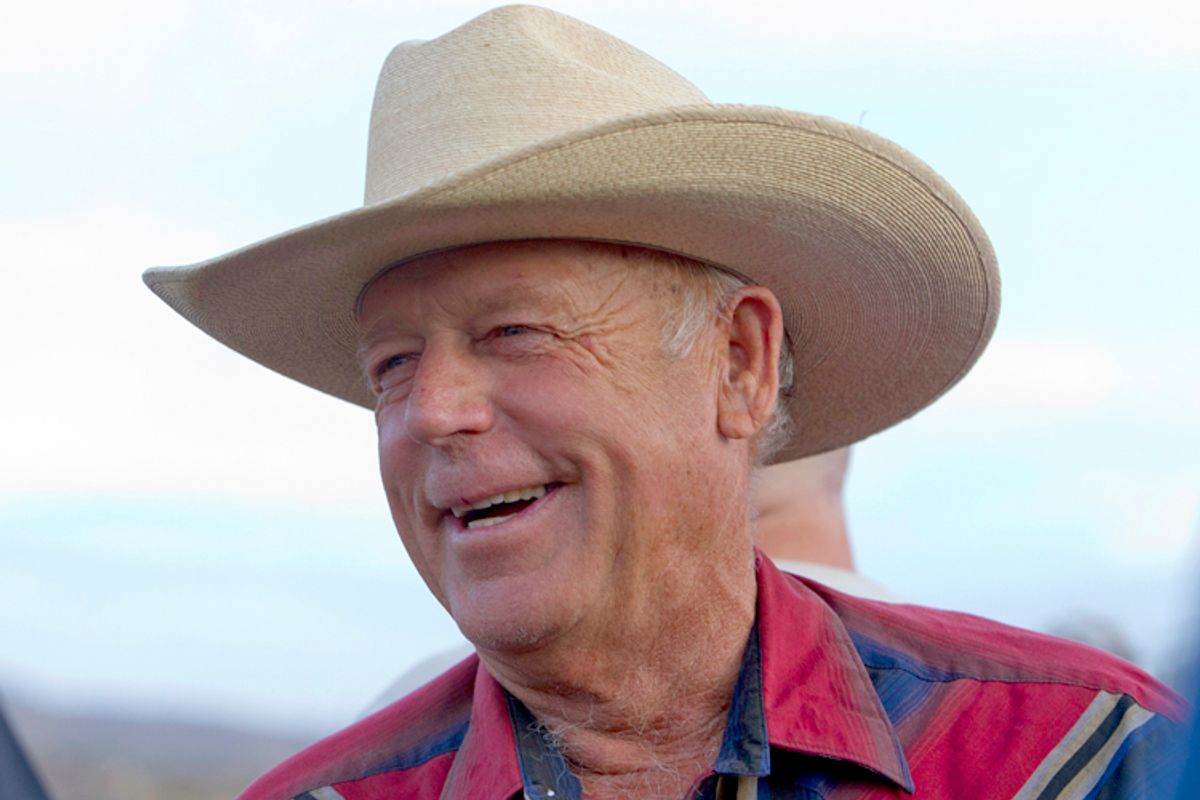

But don't worry, they're working on it! Just ask Cliven Bundy, and his army of gun-toting friends.

Shares