Plantation metaphors are generally considered an inelegant way to speak about America’s ongoing problems with racial discrimination. Such metaphors seemingly gloss over the long civil rights movement, which provided the center upon which 20th-century politics pivoted. Talk of plantations make it seem as though nothing has changed.

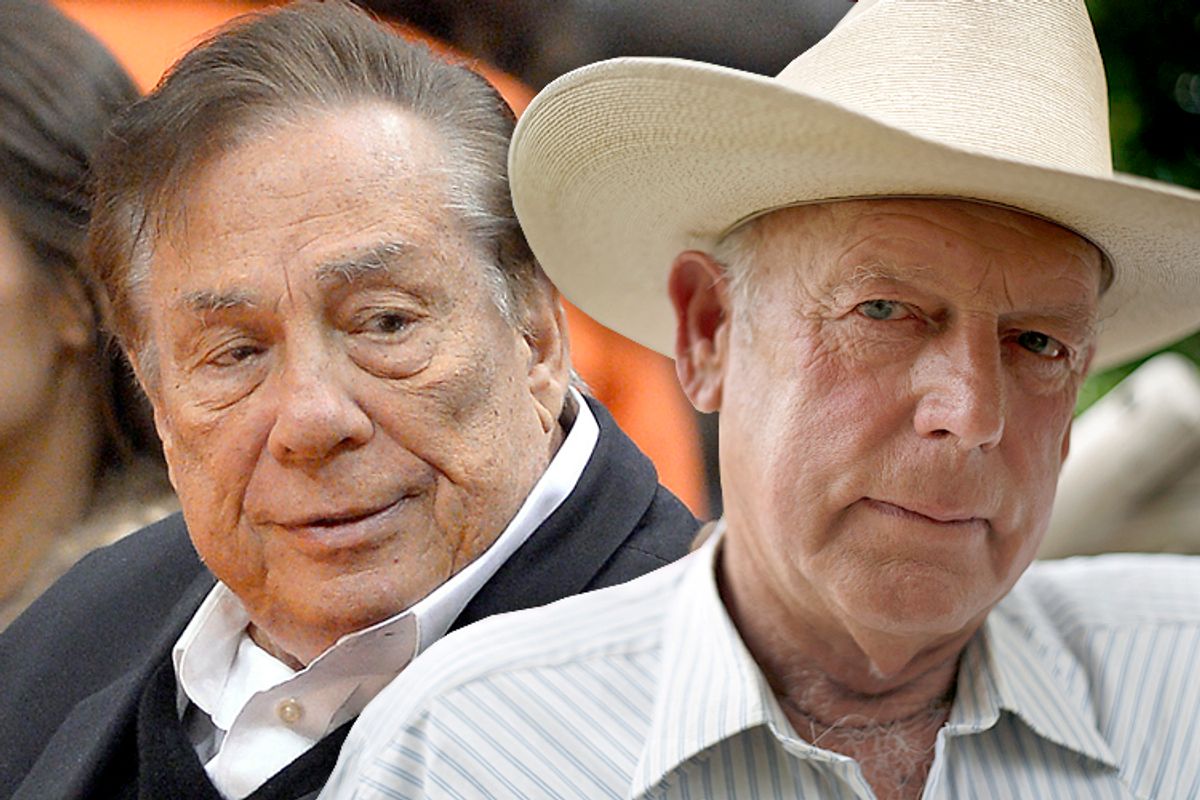

What, then, should we do when it is revealed that the Nevada rancher encroaching on public lands, who has captured the hearts of the GOP, also not so surprisingly believes that cotton picking and the institution of slavery of which it was a central part served black people well -- especially black women -- by giving us “something to do”? What should we do when the owner of the L.A. Clippers insists his mixed-race black and Mexican girlfriend not bring black people to his games, even though the majority of players on the team are black?

(After we scratch our heads at the idiocy that would cause the local chapter of the NAACP to give such a man a lifetime achievement award, after clear knowledge of multiple racist incidents in his past, then perhaps we put the choice words of Lil Wayne and Snoop Dogg on repeat.)

What should we do when the Supreme Court chooses to enable and perpetuate our national campaign of dishonesty about the continued and pervasive challenge of racial discrimination by upholding Michigan’s ban on affirmative action?

What should we do when all that shit happens to black people in one damn week?

The staggering political and historical amnesia that allowed six justices to co-sign such a policy caused Justice Sonia Sotomayor to both write and read a 58-page dissent before the court. Sotomayor rightfully suggested that those, like Chief Justice John Roberts, who believe racial discrimination will end by restricting the right of race to be a consideration hold a “sentiment out of touch with reality.” Such a view reminds me of my academic colleagues who put the term “race” in scare quotations, and tell themselves that because race is a social construction – a biological fiction – that they no longer have to think about the real material impact that centuries of race-based discourse have had on constructing a racist world.

“Race matters,” Sotomayor wrote. And “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

The dangerous, backward and wrongheaded thinking of Cliven Bundy and Donald Sterling represent just two of the most obvious iterations of these kinds of “unfortunate effects.” And we are powerless to advocate for ourselves against systemic expressions of such thinking because the Supreme Court has chosen a “see no evil, hear no evil” approach to the problem.

Though the racial views of Bundy/Sterling on one hand and the Supreme Court on the other exist rhetorically at opposite ends of the spectrum, both point to an insidious and unchecked march of continued racism that disadvantages and harms black people, in particular. Bundy/Sterling vocally promote the kind of racial thinking that makes even the most conservative white person cringe, while Chief Justice John Roberts and five other justices promote the kind of colorblind view that seems to represent the highest expression of our national understandings of liberty and justice for all.

However, what Sterling’s and Bundy’s views demonstrate is the extent to which retrograde racial attitudes are alive and well among white men with money, power and control over the livelihoods of black people. And what the Supreme Court’s abdication of responsibility suggests is that the government has no responsibility to remedy the discrimination that clearly still exists in institutions that are run largely by white men who belong to the same generation and school of thought as Bundy and Sterling.

Bundy and Sterling represent a kind of past-in-present form of racism, one that contemporary generations of white youth have largely rejected in favor of a kind of multiracial, post-racial worldview. If we would only wait on time, this view goes, Bundy, Sterling and the likes of them will die off.

In its place, I want to forthrightly suggest, however, that we will not find a cosmopolitan racial future awaiting us; rather we (people of color) will be led to the slaughter by the likes of Paul Ryan, our August Ambassador for Austerity, and his suit-and-tie-wearing goons. At the fore of these colorblind approaches to social problems will be jovial, optimistic youth of all colors who balk at the notion that affirmative action or any affirmative remedies for ameliorating centuries of government-sanctioned inequality are either just or necessary for the functioning of the body politic.

Like Cliven Bundy and Donald Sterling, the right has no problem extracting and exploiting the labor of black and brown people for the gain of white people. The right has become more sophisticated at enacting such policies without reference to race, a view that supposedly means these policies are devoid of ill racial intent. Yet to quote Proverbs, “two cannot walk together unless they agree.” And despite Jonathan Chait’s desire to insist that those of us on the left come to conclusions about the racial intentions of those on the right in bad faith far too often, we are left with last week’s right-wing sycophantic spectacle in support of Bundy.

As for Donald Sterling and the NBA, scholars of sport and race have long pointed out how professional sports are set up in a kind of plantation structure, in which mostly black players, are literally bought, sold and traded, and paid a paltry amount in comparison to the owners of the teams for which they work. If we bring NCAA basketball into this picture, the comparisons are even more compelling.

What is most interesting here is the way that black women are maligned in the racial analysis of both Bundy and Sterling. Bundy suggests that since the end of chattel slavery, black women have been left to their own devices where we now engage in a revolving door of pregnancy and abortion. Moreover, he says, “their older women and their children are sitting out on the cement porch without nothing to do. You know, I’m wondering are they happier now under this government subsidy system than they were when they were slaves and they was able to have their family structure together and the chickens and a garden and the people have something to do?”

I guess all those histories about how slavery tore black families apart are mere left-wing propaganda.

As if rooting alleged social pathologies like the non-nuclear family within the bodies, moral and sexual choices of black women weren’t enough, Donald Sterling takes up the flip side of Cliven Bundy’s prurient narrative of black women’s bodies in his demands that his girlfriend not associate with black people.

Sterling tells his mixed-race girlfriend that he has a problem with her associating with black people because she’s “supposed to be a delicate white or a delicate Latina girl.” Uhm, what? First, she is black and Mexican. Second, the way this conversation is constructed black women are intrinsically indelicate, which means in this context unfeminine and unworthy of protection.

And unfortunately even though she seems to understand the fault lines and faulty thinking in Sterling’s comments, his girlfriend V. Stiviano also says, “I wish I could change my skin.” White supremacy breeds just this kind of apologetic self-hatred, such that this woman apologizes for being born in the skin she’s in. I seriously hope that sister gets free. Surely she knows that we are off the plantation, and we can choose not to love racists.

Plantation scripts may be inelegant. But they continue to resonate because they allow us to tell indelicate truths about America’s continually reinscribed and remixed disdain for black life and possibility. They remind us that racism is constituted through a heady mix of individual offense and systemic abdication of responsibility by the powers that be. They show us the extent to which America still has an illicit love affair with white supremacy. The plantations themselves may be gone, but plantation nostalgia and plantation politics still deeply inform American life. Plantation politics are supplanted not by individual or collective acts of symbolic protest but by strong leadership that commits to ameliorating racial injustice. What we should do in the face of such staggering steps backward remains to be seen, but it is clear that we must do something, or else it is America’s race politics that will have the sole distinction of being off the chain.

Shares