No one’s heart should bleed for Donald Sterling – and pretty much no one’s does. Even Fox News, Rush Limbaugh and the New York Post have made little or no effort to defend the disgraced owner of the Los Angeles Clippers, whose public banishment by NBA commissioner Adam Silver, and public shaming by the mainstream media, was the principal vaudeville act in this week’s American political theater. Indeed, the entire purpose of the Sterling episode, from a societal point of view, was to demonstrate that we can all unite in viewing him as a dreadful person, and righteously proclaiming that his brand of cranky-old-guy racism, so reminiscent (for many white people) of debauched great-uncles at family gatherings, is no longer acceptable.

Sterling, to put it simply, is a scapegoat, whose ritual sacrifice may make us feel better about ourselves but does absolutely nothing to address the bizarre racial dynamics of American professional sports, and still less the institutional racism of our society. His only defenders are a handful of right-wing Twitter trolls who misunderstand the constitutional guarantee of free speech, or who fail to grasp that the NBA is not some socialistic Big Brother nanny state, but rather a private billionaires’ club with wide latitude to set and enforce its own rules, capricious or otherwise. It’s easy to mock those people, but in their bewildered fashion they’re flailing toward a valid point: Sterling was punished for making private remarks that threatened to embarrass the NBA’s burgeoning global brand, but only because they wound up on TMZ and fueled a zillion tabloid news stories. Sterling’s well-documented history of alleged racial discrimination and noxious racial attitudes – encompassing not just words but illegal conduct that injured real people in the real world -- never caused that kind of stink, and didn’t matter.

I’m not defending Sterling in the slightest by saying that this saga does not in fact show America at its best, and does not demonstrate how far we have come and what enlightened attitudes we now hold. It demonstrates something entirely different: Our eagerness to be distracted by symbolic narratives that embody a lot less meaning than they seem to, rather than confronting conditions of genuine social crisis and economic contradiction. We love the Sterling drama precisely because it’s a great story, with undertones of 18th-century comic opera: The aging lecher, representative of the ancien régime, who throws over his wife for the younger mistress, who turns out to be a complicated character possessed of her own agenda; the private utterance (in French farce it would be a letter) whose revelation strips the ancient troglodyte of his power and reduces him to bathos. All that’s needed is the Figaro, the younger lover with a democratic spirit who sweeps up the girl and sets everything right. That would be us.

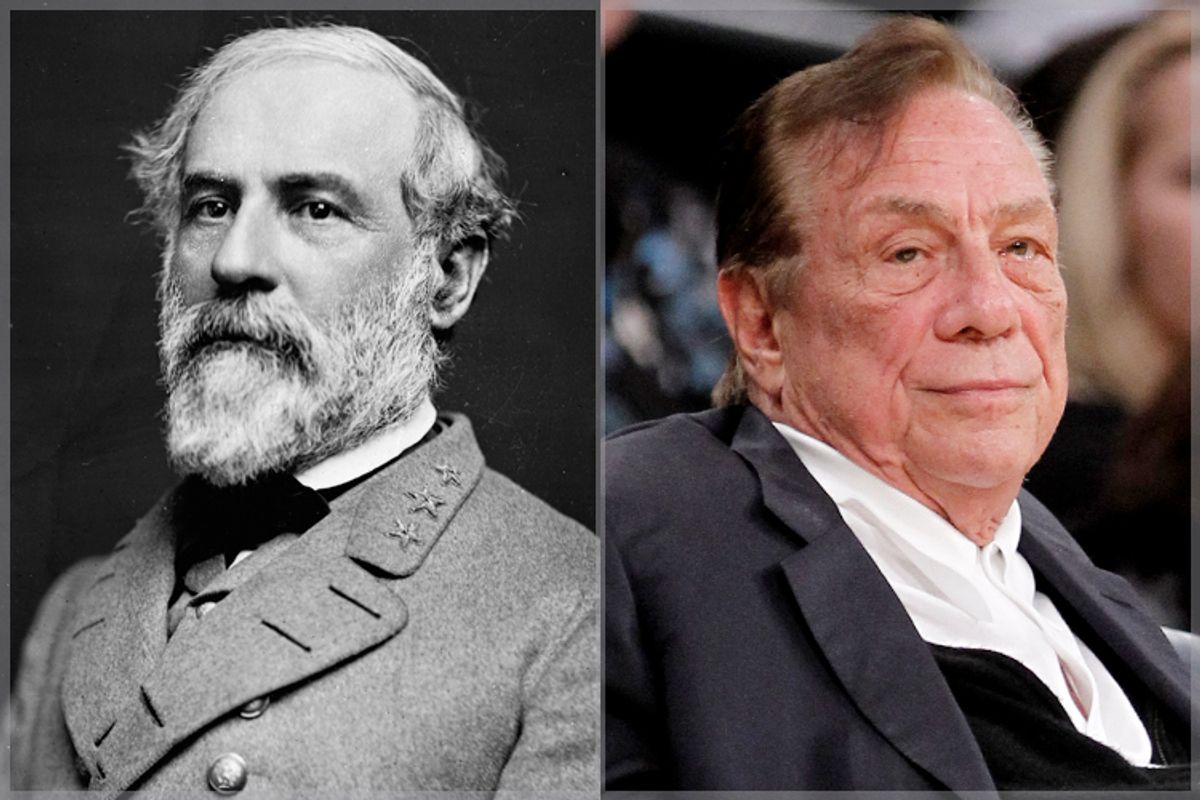

None of this, frankly, has anything to do with anything. It’s empty feel-good, just like the portrayal of Adam Silver as some kind of civil-rights hero, taking a courageous stand against the second coming of the Confederacy. I have no reason to doubt that Silver is a decent person with progressive racial views – one would hope so, at the head of a sport dominated for decades by African-American stars – but the encomiums heaped upon him this week feel like desperate projection. What I saw on television the other day was a CEO zealously protecting his immensely lucrative global business from the damage caused, in effect, by a rogue employee. As the International Business Times’ careful reporting of the story suggests, Silver initially contemplated a much lighter penalty for Sterling – after all, Silver’s mentor and predecessor David Stern had tolerated an overtly racist owner for many years. Faced with a possible player revolt, the flight of corporate sponsors and widespread public outrage, Silver was literally compelled to inflict the maximum penalty.

During the same week America’s still-ugly racial reality intruded, in the form of the state of Oklahoma brutally botching the execution of an African-American convict, a story that got perhaps one-tenth the coverage of the Sterling affair. Tarring and feathering Donald Sterling might make for entertaining spectacle, but it does nothing to address the unequal application of the death penalty. Oklahoma is an overwhelmingly white state, for instance, where almost half the men awaiting execution are African-American. Maybe that’s no mystery to the Donald Sterlings of the world, but to the rest of us it feels like a painful product of American history. Nor does the NBA’s battle of the billionaires mitigate the prison-industrial complex that has incarcerated black and Latino young men by the millions, or begin to correct systemic conditions like economic inequality, dysfunctional public education, environmental poisoning, urban “food deserts” and epidemic levels of asthma and obesity, all of which afflict poor people in general and people of color in particular.

America’s professional sports leagues have evolved considerably since the 1960s and ‘70s, when pioneering sociologist Harry Edwards described sports as a “plantation system” run by rich white men, whose wealth was largely created by the underpaid or unpaid black men beneath them. From LeBron James down to the 12th guy on the Charlotte Bobcats’ bench, NBA players of the 21st century are extremely well compensated, not to mention better educated and better informed than their counterparts of previous generations. You risk sounding like a tone-deaf radical scold, immune to the brash allure of one of our culture’s unifying rituals and engines of meaning, if you observe that the fundamental structure observed by Edwards remains in place and that pro sports is a powerful force of collective hypnosis and social distortion. All but two of the NBA's 30 principal owners are white, while more than 80 percent of the league's players are black. The NBA can offer jobs to a few dozen Moët-guzzling superstars and a couple of hundred bench players, atop a pyramid of tens of thousands of aspiring athletes who won’t make it anywhere near that far, and who are exceptionally likely to end up with poor educations and few marketable skills.

As the players have gotten richer, so have the owners – a lot richer, and a lot faster. Maybe Stern and Silver tolerated the obviously despicable Donald Sterling for such a long time because no NBA owners were terribly anxious to attract scrutiny to the extent, or the origins, of their wealth. There’s no such thing as clean money for people who have that much of it, and almost every NBA owner hit it big in some predatory industry: banking, real estate, venture capital, private equity, commodity trading and so on. (Denver Nuggets owner Stan Kroenke took a more direct route, marrying a Wal-Mart heiress.) Do they really want all their past business deals explored, and all their private off-color conversations exhumed, as has now happened with Sterling? Do the trendy fans of the trendy Brooklyn Nets really want to know how owner Mikhail Prokhorov accumulated his billions, seemingly overnight, from the privatization of the Soviet Union’s natural resources?

Beyond the practical lessons that may have been absorbed by Prokhorov and his peers – make sure your girlfriend’s not wearing a wire! – the Sterling story provided everyone in our society, whether liberal or conservative, rich or poor, black or white, with an invaluable opportunity to speak out against an embarrassing, old-fashioned variety of racism that history has already left behind. It still exists, of course, but even the Republican Party has learned that overtly racist rhetoric is counterproductive, largely because it makes too many white people who are sympathetic to more coded forms of racism feel bad. Lee Atwater and George Wallace, could either be dredged up from the fiery deluge and utter darkness of hell, would have joined in the chorus: Even if your political fortunes depend on exploiting racial animus, and especially if you represent a party whose identity rests on a massaged and sanitized version of white supremacy, you can’t say that stuff, quite that way, anymore.

Consider the enthusiasm with which right-wing elected officials in the South seize on racist hate crimes, at least when committed by socially marginal poor whites. The three men who killed James Byrd Jr. in 1998 by dragging him down a Texas road behind their pickup truck – one of the most infamous crimes of its era – were described in the press as “white supremacists,” but had conspicuously failed to take advantage of their white privilege. What they really were was small-town losers and career criminals, with prison-house swastika tattoos and copies of “The Turner Diaries.” Their act of pointless and vicious cruelty gave the suit-wearing race-baiters of the Texas Republican Party – including then-Gov. George W. Bush and his successor, Rick Perry -- a chance to distance themselves from the old, bad racism of the Klan years, and to prove that the death penalty was color-blind by inflicting it at some backwoods crackers. (James Byrd’s son, on the other hand, became an anti-death penalty activist, and has worked to save the lives of the men who murdered his father.)

Donald Sterling hasn't murdered anyone, and presumably doesn't have any Nazi tattoos (he is Jewish), but this week he became the designated receptacle for all our anxiety about the history of race and racism in America, much as James Byrd's killers did. Public outrage can be an effective tool of democracy, to be sure, and forcing the NBA to expel its most odious owner evidently struck many people as a democratic victory. But what did the ritual humiliation of Sterling actually accomplish? What did it even signify? It’s consumer democracy rather than real democracy, more like voting some smarmy country singer off “American Idol” than like claiming the political power that is supposedly ours. We returned the defective billionaire to the big-box store, and in due course we'll get another one who functions as designed. We ordered Sterling punished for thought-crimes rather than actual crimes, for offenses against the symbolic order. So his punishment could only be symbolic as well, and the thing it was meant to symbolize – the coming of an enlightened, post-racist society, where the ghosts of the past are buried at last – is a fantasy.

Shares