It’s been about a week since a recording of Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling saying racist things about black people first went viral, and much of the national dialogue in the time since has been characterized by a rare unanimity. Despite our manifold disagreements and differences, it would appear that, in 2014, most everybody in America agrees that telling your mistress not to publicly associate with people of color is racist and bad. Racial politics being the perpetual source of controversy and division that it is, it was nice to imagine, however briefly, that we all were on the same page when it came to recognizing the common humanity of all Americans, no matter the pigmentation of their skin.

I hope you enjoyed this respite from the Obama era’s near-constant fights over race as much as I did, because it’s almost certainly about to end. Once the debate naturally progresses past its first stage of blanket and superficial condemnation — and once we stop talking about how offensive Sterling’s comments were and start talking about whether he should have to endure any actual, tangible consequences for them — the uniformity of public opinion is going to collapse about as quickly as Barack Obama’s first-term approval rating among whites. In fact, we can see it happening already.

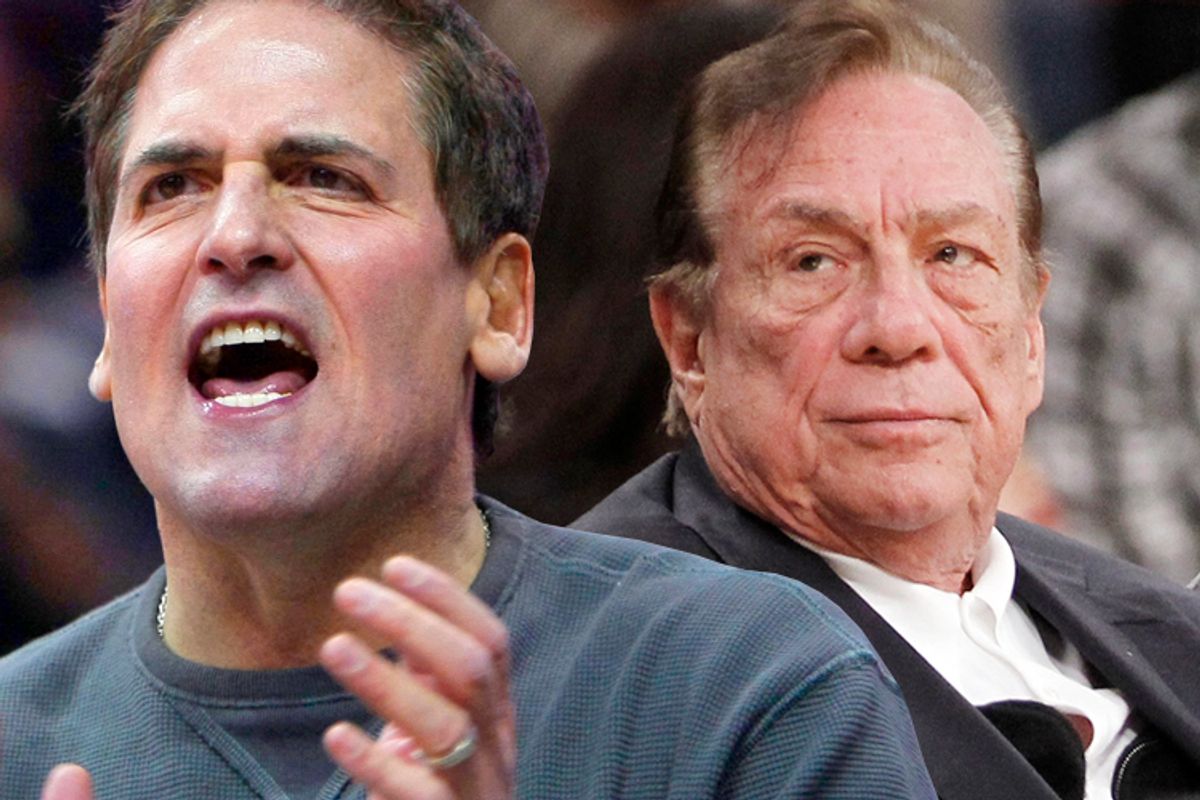

The first sign of a crack in America’s temporary anti-racist popular front came early and was courtesy of Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban. In the midst of the first wave of widespread anti-Sterling sentiment, before NBA commissioner Adam Silver had slapped the longtime Clippers owner and wealthy slumlord with a lifetime ban, a $2.5 million fine and a warning that his days as a member of the NBA’s ownership fraternity were numbered, Cuban was already following what’s since become an increasingly familiar script. He made sure to let everyone know that he didn’t think Sterling’s comments were anything other than “abhorrent,” but also cautioned against actually doing anything about them, saying that punishing Sterling for being an unreconstructed bigot would place the league on a “very, very slippery slope.”

“If it’s about racism and we’re ready to kick people out of the league,” Cuban argued, “then what about homophobia? What about somebody who doesn’t like a particular religion? What about somebody who’s anti-Semitic? What about a xenophobe?” Flashing the kind of historical and civic knowledge we’ve come to expect from our billionaire betters (see: Perkins, Thomas and Langone, Ken) Cuban reminded the rest of us that, “In this country, people are allowed to be morons.”

Cuban’s contrarianism got a bit of pushback at the time, but because the story was about how appalled everyone was with Donald Sterling — and not about how people disagree over the proper consequences for being appalling — his statement was ignored, or treated as just another example of his unpredictable and fearlessly individualistic nature. Aw, that’s just Cuban being Cuban, you could almost hear his apologists say. Turns out, however, that Mark Cuban isn’t the only one capable of doing the “Cuban being Cuban” trick.

Fox News’ favorite legal scholar and Civil War revisionist Andrew Napolitano, for example, soon penned an Op-Ed for the conservative network’s website making essentially the same argument, claiming that Sterling — like Cliven Bundy before him — was a real jerk, but still deserved his right to free speech. Unlike Cuban, Napolitano is a former judge, so he was savvy enough to note that the NBA is not a wing of the government and is thus not subject to the same First Amendment restrictions. “[The NBA] is free to pull the trigger of punishment to which Sterling consented,” Napolitano granted. Still, he claimed, “it needn’t do so.” Why not? Because the “most effective equalizer for hatred is the free market,” which would, he wrote, “remedy Sterling’s hatred far more effectively than the NBA” by forcing the octogenarian and reportedly cancer-stricken billionaire to sell the team, lest he endure “catastrophic” financial losses.

Cuban and Napolitano, then, were more or less on the same page: In the interest of free speech (which doesn’t really apply in this situation but, y’know, whatever) the best course of action to take in regard to Donald Sterling was to do nothing at all and either hope for, or expect, the best. “What to do with them because of their speech?” Napolitano wrote of Bundy and Sterling. “Nothing,” he explained. “I mean nothing.” Unlike other developed nations, apparently, you’re allowed to be a moron in America. And let’s not forget those slippery slopes, either.

Cuban and Napolitano weren’t the only ones who were able to discover an abstract and not-quite-applicable principle to cite in defense of leaving Donald Sterling alone. On the contrary, the past week saw a quiet but consistent trickle of commentary from those who were uncomfortable with the whole idea of sanctioning Sterling in a manner more concrete than public professions of disapproval. Once Silver had announced his unprecedented punishment of Sterling, for instance, Bill Zeiser of the American Spectator wrote an impassioned attack on the NBA, arguing that the league had — you guessed it — trampled on the Clippers owner’s right to self-expression. But Zeiser added a new wrinkle by complaining that the league only found out about Sterling’s comments due to a surreptitious recording that violated his right to privacy. “The views Sterling expressed were odious, to be sure,” Zeiser wrote, “but I'd wager that we've all said and done odious things behind closed doors.” Let he who has not forbid another from publicly socializing with black people cast the first stone!

Like Zeiser, A.J. Delgado of National Review and Cato’s Julian Sanchez were also very, very worried about the Sterling precedent. No, not the precedent of having a well-documented bigot welcomed with open arms by the NBA and members of the NAACP for decade after decade; but rather the precedent of having a man lose his privileges for something he said when he thought no one would listen. “Were Sterling’s comments appalling?” Delgado wrote. “Of course. But they were said in a private communication. Surely that must count for something?” Sanchez, similarly, tweeted that Sterling’s response to the whole controversy should have been, “‘It’s none of your business what I said or why during a private phone call.’” (That wasn’t Sanchez’s only smart take on the issue, though; he soon followed up by explaining he “[didn’t] really give a shit either way,” no doubt strengthening his followers’ convictions that they should take his deep thoughts very, very seriously.)

And as is almost always the case, one did not have to look very far to see the arguments offered by these plutocrats and conservative pundits echoed — albeit with far less sophistication — by the general population. On Twitter, there was a boisterous chorus of constitutional experts who couldn’t believe free speech in America had become so meaningless; and in the pages of the Washington Post, there were readers arguing that punishing Sterling would be a mistake and that it would be much wiser for all involved to treat the incident as “a teachable moment in race relations” because “offensive speech made in a private conversation should be treated differently than publicly conveyed hate speech.” Why make Sterling sell the Clippers, one reader asked, when you could encourage him to do so and, in the process, begin his attempt to “seek redemption”? After all, isn’t Donald Sterling the real victim here?

Taken together, these pseudo-defenses of Sterling hardly constitute a consensus of enough scope to rival what still remains the mainstream response to the Sterling recording, that he is an odious racist whom the NBA should’ve booted long, long ago and still can’t get rid of soon enough. But they do show that, if you scratch just a little past surface, you’ll find Americans aren’t actually as “evolved” on the issue of race as the intensity of the Sterling demonization might lead you to believe. For many Americans — mostly but not exclusively Republicans and conservatives — what Sterling said is to be condemned (“to be sure,” as many of the authors mentioned above like to say), but not in the same way that, say, shoplifting or speeding is, with material consequences. Instead, Sterling-style racism should be considered as a kind of extreme faux pas, as if it were essentially no different from texting in a movie theater or lecherously staring at your friend’s partner on a dinner date.

Ta-Nehisi Coates of the Atlantic recently described Sterling’s sin as an act of “oafish racism,” a ham-fisted and unsophisticated style of bigotry that most Americans are happy to condemn while leaving “elegant racism” — manifested in dog-whistles, redlining, and the carceral state — untouched. This isn’t an objection I expected to levy against the clear-eyed and unflinching Coates, but I think that in this regard he may actually be giving us too much credit. It’s true that many or even most of us find Sterling’s oafish racism contemptible; but as Cuban, Napolitano, Zeiser and the rest show, even that sentiment isn’t as widespread as you’d hope. Few will outright defend Donald Sterling, sure. But some of the most influential among us are seemingly willing to walk up to the precipice of that very, very slippery slope.

Shares