On Sept. 21, 2001, Rais Bhuiyan, a Bangladeshi immigrant, was working in a gas station minimart in Dallas when a burly man with tattoo-covered arms walked up to the counter and pulled out a shotgun. Bhuiyan moved to hand over the money in the cash register, but the man seemed uninterested in that. "Where are you from?" he demanded to know, before shooting Bhuiyan in the face.

Although the shotgun's pellets missed Bhuiyan's brain by millimeters, 35 of them remain lodged in his body to this day; he is nearly blind in one eye. His would-be killer, who apparently thought he'd finished Bhuiyan off, had already killed Waqar Hasan, also a convenience-store worker, and would go on to kill another man, Vasudev Patel, 11 days later. When he was caught shortly afterward, Mark Stroman, who mistakenly believed that his victims were Arabs, would claim to be an "allied combatant" in the newly declared war on terror, a self-proclaimed "American terrorist," striking back at those who, he wrote, "sought to bring the exact same chaos and bewilderment upon our people and society as they lived in themselves at home and abroad."

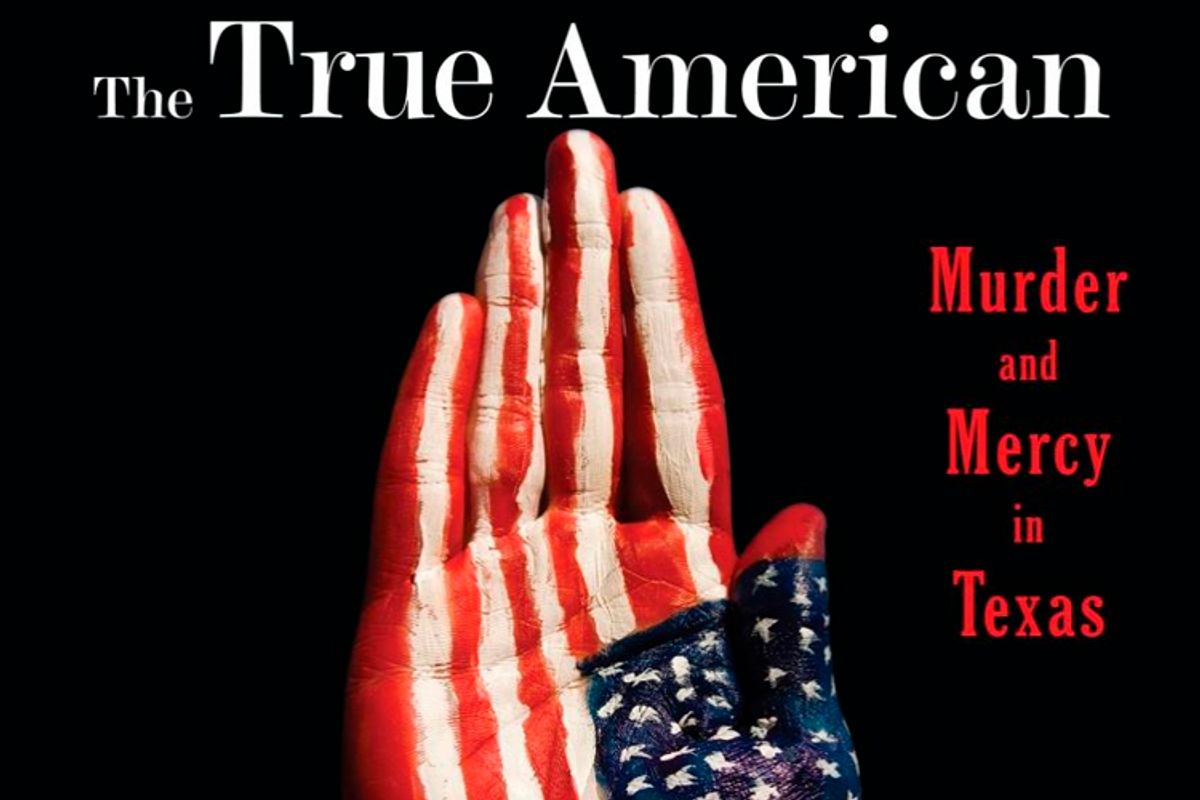

Stroman turned out to be an ex-con and rumored member of the Aryan Brotherhood with a long history of trouble with the law. Despite his belief that hate-crimes legislation levied extra punishment on people like him, prosecutors had to try him for killing Vasudev Patel while committing the crime of robbery because only then was he eligible for the death penalty. Nevertheless, as the prosecutor acknowledged to Indian-American journalist Anand Giridharadas, whose moving and indelible "The True American: Murder and Mercy in Texas" tells the extraordinary story of Stroman's crime and its aftermath, it was the hatred behind Stroman's actions that made the state's attorneys determined to send him to death row. They succeeded.

What makes Stroman's story exceptional isn't, alas, the blustering, ignorant, brutal travesty of "patriotism" that motivated it, but the way that the sole survivor of his spree decided to respond to it. Bhuiyan struggled to overcome his misfortune for several years, losing his fiancée back home, undergoing four surgeries and ending up $60,000 in debt. But thanks to a generous doctor, a victim's compensation fund and a good deal of wrangling and persuasion, Bhuiyan finally got his head above water. He landed a job at the Olive Garden (a challenge, as Bhuiyan, a devout Muslim who had never touched alcohol, had to master the art of selling wine and cocktails), took a training course and finally attained the IT job he'd been aiming for when he moved to the U.S. (A trained air force pilot, Bhuiyan will never be able to fly a plane again due to his impaired eyesight.) He became an American citizen, fulfilled a lifelong pledge to take his beloved mother to Mecca, and then, at last, he turned to the promise he'd made to God as he lay bleeding on the minimart floor in 2001: to dedicate his life to doing good works.

Bhuiyan realized he was uniquely situated to, as Giridharadas puts it, intervene in "the cycle of mistrust and enmity between his religious community and his adopted country -- between Islam and America." He would do so by publicly forgiving Stroman, petitioning the state of Texas to spare the killer's life and, if all went according to plan, enlist the one-time neo-Nazi sympathizer in a campaign to foster understanding and educate his fellow rednecks on the dangers and stupidity of white supremacism and Islamophobia.

It's a manifestly inspirational story, the kind easily told in a newspaper article to which readers can and have attached comments marveling over the human capacity for goodness and the irony of a Muslim behaving with greater Christian charity than the jingoistic Bible thumpers all around him. Bhuiyan became a potent public speaker. When he finally got the chance to make his plea for Stroman's life at a hearing on the day the execution was scheduled to take place, his words left listeners -- including that most stoic of all legal professionals, the court reporter -- in tears.

However, Giridharadas, a columnist for the New York Times, does much, much more with this tale than craft it into a slice of Upworthy-style sanctimony. "The True American" offers not only a portrait of the exceptional Bhuiyan but also an in-depth account of the average, ragged lives of the Stroman family: Mark, but also his ex-wife and children, all of whom wrestle with the same problems that bedeviled their father: drugs, alcohol, criminality, disintegrating families, violence and poverty.

Stroman would eventually renounce his former racist beliefs and actions, although some skeptics (including his own sisters) question the authenticity of his remorse. It was not lost on the condemned man that, during his final years on death row, it was a passel of mostly foreign strangers -- above all the Israeli documentarian Ilan Ziv, but also assorted international opponents of capital punishment -- who tried to help and reform him; his family, by contrast, made themselves scarce. During his first days in prison, however, Stroman was unrepentant, claiming, "We're at war. I did what I had to do," and mouthing other grandiose, macho and ultimately empty mottos lifted from movies and popular songs. He circulated a manifesto -- taken from the Internet and containing the usual denouncements of government, gun control, liberals, racial minorities and immigrants -- to which he gave the title "True American."

The irony, of course, is that Bhuiyan, with his indomitable optimism, energy and determination, is much truer to the American ideal than the man who tried to kill him. In "The True American," Giridharadas portrays two cultures contemplating each other, not so much Muslim/Bangladeshi and Texan as two versions of America itself. One, Stroman's, looks back from a faltering present to an idealized past. "He felt himself and people like him to be standing on a shrinking platform at which minorities and immigrants and public dependents were nibbling away," Giridharadas writes. The other side, Bhuiyan's, looks toward the future and puzzles over the established Americans' inability to seize their opportunities and shape their fates. "You guys are born here, you guys speak better than me, you understand the culture better than me, you have more networks, more resource [sic]," Bhuiyan imagined asking Stroman's people. "Why you have to struggle on a regular basis, just to survive?"

Bhuiyan has a few theories about that, not all of which Giridharadas endorses. But what both men seem to concur on is the broken nature of poor white American communities, particularly the weakened ties between parents and children. "So much lonely, so much alone, even detached from their own family," Bhuiyan tsked when he looked around him after first arriving on these shores. (That -- however much he respected, loved and felt indebted to them -- he'd still left his own parents behind in Bangladesh suggests that Bhuiyan may not find American isolationism a totally alien impulse.)

In the final chapters of "The True American," Giridharadas recounts hanging out with Stroman's troubled daughters and ex-wife over the course of a few days, delivering a finely textured portrait of lower-class despair and excruciatingly incremental struggles to regain control of life. This is where the power of his book makes its deepest impression, where it becomes more than Bhuiyan's tale of immigrant gumption and almost superhuman mercy. Not that Bhuiyan doesn't remain a shining figure, one of those individuals the rest of us want to cluster around like a campfire on a chilly night, but the truth is that most of us are a lot more like the Stromans: blinkered, self-justifying and swamped by our circumstances. This juxtaposition of the clay-footed reality of most lives with the incandescence of our potential pretty much defines not just the American condition, but the human one, as well. The whole story will always include both.

Shares