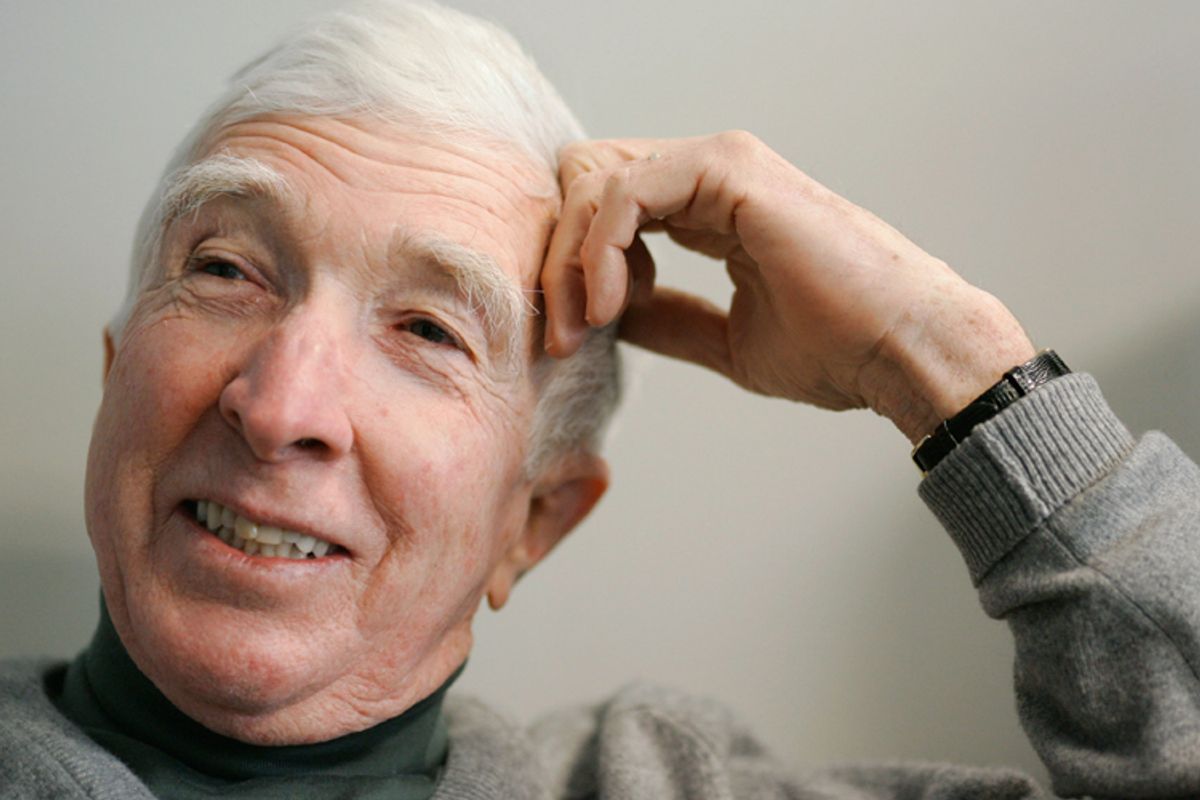

In an early letter to his mother, John Updike wrote that America needs a writer who desires both to be great and be popular," and "a writer who can see America as clearly as Sinclair Lewis, but unlike Lewis is willing to take it to his bosom.” And then he went off and became that writer, as Adam Begley writes in his terrific new biography "Updike," with as smooth a climb to the top of American letters as any novelist has ever had.

Updike's mother, Linda, married his father in part because they believed they would have a very special child. She nurtured and encouraged and indulged, and the small Pennsylvania town where he was raised provided the backdrop and the grounding for his sensibility and his work. Well, that small town, plus the Northeastern elites -- Harvard, the New Yorker, WASPy Boston of the Back Bay and the Shore -- where he spent the rest of his life.

It was a life lived very much on the page -- among two of the most popular Updike criticisms are that he never had an unpublished thought, and that he was simply writing his life. And that's a challenge for Begley, whose book blends biography with a brilliant close read of Updike's work, especially his early novels and short stories. But it also means there's lots of sex, adultery and interesting mommy issues in real life!

If Updike isn't read in quite the same way today as he was during his Rabbit heyday -- if some of the writing seems fusty or flowery, if his problems with women jump off the page, if there seems no easy entry into many decades of publishing his every thought -- Begley's biography, as insightful on the work as the life, is a complicated and fascinating portrait of one of the great literary lives of the second half of the 20th century.

We spoke over lunch last month about Updike and women, Updike and Philip Roth, Updike and Ted Williams and that scathing David Foster Wallace review that Begley assigned at the New York Observer. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

One of the fascinating things about John Updike -- which also informs the structure of your book -- is how close the fictional Updike aligns with his life and his autobiography. You’re able to write his biography while also doing this wonderful close read of the short stories and his work.

People keep asking me, how do you write a writer’s life? All they do is sit at home in a room and write. What’s there to say? In Updike’s case there’s this tremendous resource, which is that his fiction parallels his life so closely that whenever you run out of exciting incidents, you can turn to the fiction and you’ll find pretty much a parallel to what’s happening in his daily life. More than that, you get trace clues of how he’s feeling, because most of the stories aren’t just impresses of private life, but impresses of private life artistically arranged and sharpened. You get a theme, you get an idea, you get a new way of looking at the world. And it became, it was certainly a crutch for me, and I hope it didn’t become a bad habit. But every time I was feeling insecure about writing his life, I turned back to the text and came away refreshed.

So after studying his life, what percentage of his fiction would you say is autobiography?

There are very few Updike works that do not contain an element of autobiography. Even novels as far afield as “Brazil” and “The Coup” contain every now and then little details that he filched from his daily life. “The Coup” is about an African dictator, but that African dictator went to college in the Midwest in the 1950s and so suddenly you’re getting -- I mean, he obviously has the experience of a black man in these circumstances, but it’s still Updike’s experience you’re sometimes getting in the novel, transmuted. I’d say magically transmuted. One of the joys of reading Updike when you know his biography is not just seeing what he took from his life but what he did with what he took from his life.

That’s an important distinction. This is not simply a life on the pages, this is a very artistically arranged life in fiction, but also in real life, from the way he presented himself in public, in letters, in communications with editors and publishers, or in interviews. Every pretense – and there were many – was thought out.

He was a consummate professional. This is a characteristic of his behavior from the very beginning -- his first contact from his very first editor. His letters to her are so full of attention to detail, and he’s so careful in his dealings with her. And that goes on even six decades later when he’s got new editors at the New Yorker, and he’s writing to them with the same care, the same courtesy. He’d look at every aspect of his work down to the layout on the page, the font size. He took the business of writing as seriously as he took the words on the page.

Does his reputation suffer today because people have not separated the work and the man? Because people think the novels are mere autobiography?

He did get knocked for that. There’s a Harvard professor who dismissed him in the mid-’60s as someone who merely took anecdotes from his life and poured them on the page. He’s got a point at some level. Take a story like “The Happiest I’ve Been,” which tells the story of a college junior going back to visit his mother’s farm.

This is the New Year’s party.

Yes, the New Year’s party. That is really very specifically an account of an incident that occurred. I can document exactly whose party it was and who was there, and when Updike was invited -- and the tiniest details are verbatim in a lot of ways. But if you read the story without knowing that, it’s tremendously powerful anyway. And I think you don’t lose anything, really, by knowing that he was essentially taking from life.

What challenges does that present as a biographer, to realize there are so many clues right there in the work in front of you – but perhaps you can’t take them too seriously. Perhaps he’s pulling from something that really happened and you uncover the story, but perhaps this is a man deeply interested in his image, dropping bread crumbs for his biographer to find.

I can tell you that it made me very careful. Because I realized there was a risk of taking for granted that something in a story was actually true. Generally, 90 percent was true. But then that 10 percent you’ve got to be careful about. For example, there was this incident in one of the last of the Maples stories, “Here Comes the Maples,” where Richard and Jo Maples get divorced. And in that story Richard Maples, who is the stand-in for Updike, recalls that at his wedding he forgot to kiss the bride. And then after the divorce ceremony, the judges are talking with the lawyers and Richard thinks what to do – and he steps over and kisses his wife who he’s just divorcing. And of course I had to check that. It’s a very poignant detail. It works beautifully in the story. It turns out to be absolutely true. Mary Updike confirmed that in the confusion of the wedding, he somehow missed the kiss business, and that indeed, he did kiss her at the divorce ceremony.

At a very young age, Updike writes to his mother that we “need a writer who desires both to be great and be popular, a writer who can see America as clearly as Sinclair Lewis, but unlike Lewis is willing to take it to his bosom.” And then he goes off and does it.

It’s an extraordinary quote. One of the amazing things about Updike is that he tended to write his life before he lived it. That quote is a prime example. He engaged in a very long correspondence with his mother, which is very much about being a writer in America -- because she wanted to be a writer and he wanted to be writer, and he wanted her to be a writer, and she wanted him to be a writer. So it was a kind of mutual admiration society, mutual encouragement society. That particular observation to his mother, it can be read as a prefigurement to the Rabbit books. Which is astonishing. But it also begins to show you how extraordinarily ambitious he was, even from a very young age.

The other part of that quote that’s interesting is the idea that he wants to make it into the American hearts, that he wants to be popular. And this reflects his early desire to reach a wide audience, which really began when he wanted to be an animator.

He wanted to be the next Walt Disney.

He never quite made it to Walt Disney level.

Well, he made it to the cover of Time magazine.

Twice. Once with "Couples," and once with "Rabbit is Rich."

I think the novel’s place has become so lessened, that it feels so impossible to reach that vast American middle, that I’m not sure if many writers see that as possible any more.

Jonathan Franzen makes a bold effort.

And has a very complicated relationship with that effort! Also, a complicated relationship with Updike, right?

Jonathan has very harsh words for Updike. And I remain convinced -- and I admire Jonathan’s work and I’m fond of Jonathan personally -- but I believe that he’s suffering from a bit of anxiety of influence here. That he feels the need to denigrate Updike because his project is really not very different from Updike.

You also note the ease with which he accomplished such a difficult feat as the one he lays out in the letter to his mom. “Among the other 20th century American writers who made a splash before their 30th birthday … none piled up accomplishments in as orderly a fashion as Updike or with as little fuss.” It’s a very charmed professional life – he worked hard, put himself in the right places to be noticed, and was pulled right along.

He was a man who did the best with what he had. There is a little caveat there about the smoothness of his progression. One of them is that he felt in some ways that he had overcome some hurdles. One of them was his stutter, which came on when he was about 15, and afflicted him pretty much all his life.

And then the other affliction he had overcome was psoriasis, which afflicted him when he was about 5 or 6 years old, and he had a terrible case as a young boy. It didn’t really go away until he was in his thirties, when he found an effective treatment in Boston at Mass General. Again, most people didn’t notice that he had psoriasis, but he himself felt that his body was hideous in some ways.

Did not seem to affect his sexual self-confidence.

No it didn’t. But I have to say that was after his first wife had, more or less, can we say, fortified him against his own self-loathing.

Could he have lived this life without a mother who very clearly had great ambition for him, nurtured him very carefully and believed from the very beginning that she was giving birth to someone very special and important?

I think she was tremendously important to his career. Just the business of watching her write was very important for him. But then at an early age he was called upon to edit her work, which is a little weird. As early as 10, she was giving him stories and saying “What do you think of this?” She wasn’t a brilliant writer. Her work in The New Yorker was a little emotionally overwrought and the mythologizing of her life gets a little heavy. I think without his assistance she never would have gotten a story in The New Yorker. But nonetheless she was trying, and he saw her trying, and it gave him the impulse to do the same.

To do the work.

To do the work. And also, I quote Freud as one of my epigraphs, that being the adored object of your mother gives you for the rest of your life the feeling of a conqueror. I think there was a sturdy layer of self-confidence in John, instilled by his mother. There are a lot of great artists who are the apple of their mother’s eye; it’s not a rare phenomenon.

Then he goes to Harvard, and his roommate is Christopher Lasch.

You couldn’t make it up. It’s a strange relationship. They got along for about a year, but even then Christopher Lasch was a bit of a grump; he was an angry man all his life.

You can see where "Culture of Narcissism" comes from, in his letters home at 18.

Yep. But of course John’s mother was an angry woman. And John had learned to placate his mother, and he learned to placate Christopher -- Kit, as he called him. And they, I think, egged each other on, and pushed each other to greater academic feats. It’s weird enough that they were roommates, what’s even weirder is that they then both graduate summa, that Kit Lasch gets the prize for best thesis, and Updike gets the No. 2 prize. I mean, I don’t suppose it’s ever happened before in the history of Harvard, freshman year roommates getting No. 1 and No. 2 essay prizes, and graduate summa. It’s an extraordinary coincidence.

And biographical gold because there are all those letters.

The letters that Kit Lasch wrote home to his parents about Updike are just hysterical.

How did you find those?

They’re at the University of Rochester.

Did you realize they were there or was it a shot in the dark, and then you discover them and then it’s like, I can’t believe I’ve got this?

That’s exactly it, and I remember the day I saw how many letters there were, and I thought, okay, I’m just going to call them up and ask them to send them to me. And I thought this’ll never happen. But no, The University of Rochester simply mimeographed them and put them all on disc and sent them to me. And I received the sheath of letters about this long. Then I started reading them and I thought the top of my head would blow off. It was delightful. And you know, nobody had thought of this before as far as I know. Nobody had looked at his letters.

They fell out eventually, you know. They really stopped getting along and the letters dwindled to nothing. John was capable of peevishness himself and never mentioned Kit Lasch in all of his writing, until he wrote a poem about him when Kit died. Now I’m sure that John was aware when he was writing “Rabbit Is Rich,” which is all about America running out of gas, that he was echoing Jimmy Carter. I mean, I know he knows he was echoing Jimmy Carter. And I’m pretty sure he knew that Jimmy Carter was echoing Kit Lasch. But none of this gets acknowledged by Updike, and I think it’s a bit of a shame. Generally he was good about acknowledging his debts, but this one went unmentioned.

Which is interesting because he’s living in Ipswich, he’s using the most personal, intimate, sexual material of friends, of folks in a small town. And it doesn’t seem like anybody ever really begrudged the use of these stories. Did people complain? Were there ruined marriages, destroyed friendships? Fewer dinner invitations?

Well, both of his wives complained at times. And interestingly his second wife complained retroactively about his treatment of the first wife on the page. But it’s true that his crew, the Couples Gang as I call them, because they’re whom he based the characters on in “Couples.” The Couples Gang never complained about their treatment. Which is amazing, because he used them not only in that novel, but in short stories all along, starting in the mid-’60s and all the way through the mid-’70s. And then he wrote nostalgic stories about the old days in Ipswich and then they, of course, reappeared. His children didn’t complain, but they resented it.

As adults?

As adults. For example, you can only guess how his eldest daughter felt when he titled a story “The Lovely Unmarried Daughters of Our Old Crowd.”

Was there something in his mind that allowed him to do this, and to continue to live amongst these people without feeling nervous or shame? I think about the poem you write about, “Taking my Children to the Dump in Ipswich,” a very raw sentiment as the divorce was happening. It had a different title when it was ultimately published in The New Yorker, but as you write, still mentions the dump in Ipswich. It takes away any veneer that this is not his life and his kids and his divorce and his marriage falling apart. He was okay turning all of this pain, his and that of his loved ones, into material because why? Because the demands of the artistic life required it?

I think it’s at heart a question of self-belief. He believed that he was doing something that was more important than the feelings of the people around him. He made a decision early on to put artistic considerations ahead of personal relations, and to put his work ahead of his friends and his family. From our point of view, we can only be grateful for that. I mean, without his belief that it served a higher purpose, we wouldn’t have a story like “Separating,” where John basically gives us the blow by blow of the meal where he informed his children, three of his four children, over lobster and champagne, that he was leaving their mother and would be moving out and breaking up the family. It’s a heartbreaking story, and almost word for word accurate to what happened that night. I believe that one of the details he changed was that he had his oldest son at a rock concert in Boston, whereas in fact he was at a jazz club in Cambridge.

He got warnings about this all along. In a very early short story, the first Maples short story, “Snowing in Greenwich Village,” he wrote about a wised-up girl who comes to see the Maples and tells funny stories about her life as a single girl in New York. And I’ve seen the letters from both that girl to John and from that girl’s boyfriend to John. And the girl simply says that it’s quite a shock to be in your bath, reading your New Yorker, and all of a sudden you find yourself on the page.

She was fairly cool about it. But her boyfriend wasn’t cool about it at all, and gave John and Mary a real dressing down. John says it ruined his weekend, and it made him reconsider the idea that an artist owes nothing to anyone except his work…

Momentarily...

And that the truth is the only way to go. But obviously he continued to do it all along. I mean, occasionally he would get called up onto the carpet, and he would have a moment of regret, but I think those moments were briefer and rarer as the years went by.

Well, the in the ’60s, he’s forced to leave Ipswich. The family is exiled to a cruise. A terrible exile though that must have been. Joyce Harrington’s husband learns about the affair with Updike, and asks him and Mary over for a conversation. The insane civility of it all. After that talk, the Updikes agree, you’re right, we must leave town for a little while. We’ll go on a cruise to the south of France.

That was the result of Joyce Harrington’s husband finding out about his affair with her. He banished John to Antibes for an indefinite period. It turned out to be only about four months. But John acquiesced. They thought it was a good idea to get out of town and let the affair die down. John remained in love with Joyce Harrington, so it was really quite necessary. But it took John about 10 minutes to start writing about, not only the affair -- I mean he was writing about that even before the affair was discovered, but also the consequences of the affair. So he writes a charming story set in Antibes about a man who doesn’t love his wife enough.

Let me back up: Updike is in New York, he’s writing what everybody seems to agree, even now, the best Talk of the Town pieces ever written. The possibility is in front of him to write about New York, to be a part of New York literary society – and he decides no, that’s not to be his topic or his life. He also thinks if he stays, and stays at The New Yorker, that his novels will suffer. Did he agonize about leaving?

Yes. It was a tremendously conscious decision. He would talk about New York not being a good place to bring up children or to hatch novels.

But he was really concerned about the novels.

Yes, it was the unhatched novels that concerned him most. He never set a novel in New York. And he never really joined the New York literary circles. Late in life, he spent a fair amount of time at the far north fringes of Manhattan at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, which provided him with a twice or three times yearly social event where he would mix with writers. But the writers weren’t necessarily New York writers; they were writers who came to the Academy from wherever they lived.

John was an only child, and John always needed to be a one-man show. He also always needed to be the center of attention. The New Yorker made that difficult for him, because The New Yorker was a corporate event. The New Yorker in those days was much less a showcase for individual talents -- all those Talk pieces were unsigned.

The names of the writers for the short stories were at the very end. You would see the title of the story, then the story, and when you got to the end there would be a little hyphen and then the name of the author. And John loved the magazine from very early on, but John needed to be an individual standout, not part of a team.

So he had to distance himself from The New Yorker, and he quite rightly realized he couldn’t be a New Yorker and at The New Yorker and keep his distance. So leaving New York was leaving The New Yorker. But also New York made him nervous. He felt crowded, he felt pushed. You have to remember, he knew very little about black people, he knew very little about Jews, he knew very little about rich people. All of these people were foreign to him. He was out of his comfort zone, to use the horrible modern cliché. He went to a place where his crowd was much more homogenous. He was shying away from New York, essentially.

Was he right? Could he have written these books if he had stayed?

I’m not saying he would have been a greater man or a greater writer if he had stayed. I think he probably, for him, made the right decision.

Did he also feel like The New Yorker simply wasn’t challenging enough?

Well, he himself said that an artist has to be doing something that is hard for him, has to constantly be seeking to improve. He didn’t think that at 24 he was ever going to get better at Talk of the Town than he was. His fear was that he would become a hack. Or as he put it, an elegant hack. And what he wanted to be was an artist. He had fallen in love with the great modernist writers at Harvard. He was in love with Proust, he was in love with Joyce, he was in love especially with Henry Green.

Not others you’d connect with Updike, necessarly.

No, I wouldn’t read most short stories or novels by Updike and say, wow, this guy has been reading a lot of Proust or Joyce. But in his devotion to making writing great, to try to find a way to connect a reader to reality in a new and special way, a more vivid and meaningful way… he was following in the footsteps of the great modernist masters. And of course later he added Nabokov to this crew.

At the time he decides to leave town, there’s a negative New York Times review of John Cheever which paints him as a New Yorker writer, and suddenly Updike felt he had to escape that. Which goes to a couple of things: What we’ve been talking about, but also the prickliness with which he paid attention to the slightest criticism and the way those criticisms got inside his head. Why did criticism stay with him? Does it all go back to his mother?

He didn’t like criticism, he wasn’t used to it. He didn’t grow up with it. It wasn’t part of his world. When the first truly negative reviews came it was not with “Poorhouse Fair” but with “Rabbit, Run,” and they were generally along the refrain of “Updike writes too well,” or “Updike is a New Yorker writer.” Both of those things got under his skin. He began to write brash letters to people, protesting.

His politics had him a little out of step with his contemporaries. Especially Vietnam.

Yes.

Where do those politics come from and how do they change over his life? If they changed.

His politics stem from Shillington, from small-town Pennsylvania that was an oasis of calm and unchanging. And that was first because of the Depression, so there wasn’t much growth going on, then you’ve got World War II. The world was in cataclysm, but Shillington was Shillington. And for him Shillington was order, and authority in Shillington was the faculty of Shillington high school.

Quite literally: It was where his father worked.

Yes, his father was his math teacher for two years, and his homeroom teacher for one year. So Updike felt questioning authority was questioning his stable world.

And then the 1960s happen.

The 1960s happen and suddenly everybody’s protesting, everybody’s out in the streets and there are snipers shooting at firemen in the streets of York, Pennsylvania, 20 miles, 30 miles from Shillington. I mean, it does look like the world’s coming to an end.

Updike was not in tune to that kind of anti-establishment agitation and he took against anti-war protests. Now he’s often called pro-Vietnam, or a Vietnam War supporter; that is completely untrue. The whole kerfuffle about Updike with The New York Times, what happened was Updike was approached by a British journalist and asked for his opinion of the Vietnam War. He wrote a very concise, very moderate paragraph explaining why the Vietnam War was an unfortunate necessity, saying that until the Vietnamese people declare a desire to be Communist we should be defending them against Communist aggression. It’s quite a mild piece. The New York Times then picked that up when the book came out and said that the only writer in the book that was pro-war was John Updike. And then John Updike writes a letter to the Times that is three times as long as the original paragraph, trying to refine his position.

You’re not going to win that fight.

He dug the hole deeper and deeper. And the whole experience was wrong for him; he was out of his depth. He shouldn’t have been talking about politics in the first place. He wasn’t a particularly politically minded character. And he became known in American culture as a conservative. In fact, he never voted for a Republican in all his life. He was a Democrat. He was a centrist or possibly left-leaning Democrat, who simply didn’t believe in civil disobedience or in protest against authority.

But he was perfectly comfortable with the cultural revolution of the 1960s, on the sexual side? “Welcome to the post-Pill paradise” and all? He was perfectly at home in the post-Pill paradise, but not particularly at home with other forms of 1960s change?

For the first time today I think I’m going to disagree with you. “Couples” is a problematical book. It is a satire. When he talks about the post-Pill paradise, he’s deploring the post-Pill paradise at some level. The problem is that Updike got so carried away with his love of describing adultery, sex, liberated women, the atmosphere of freedom, that he made the book a little unstable. The satire is buried under the mounds of gorgeous prose about how much fun all this is. He was as uncomfortable in his way about the cultural revolution as he was about the political protest. He listened to Janis Joplin and the Beatles. He smoked a bit of pot. But he continued going to church, he stayed married to his wife despite multiple infidelities. Like all of us, he wanted to have it both ways.

One of those infidelities came close to costing us one of the most acclaimed pieces of magazine journalism of the last several decades. Updike said that he might have never gone to Fenway Park for Ted Williams’ last game, never described that final home run in “Kid Bids Hub Fans Adieu,” had a woman he very much wanted to sleep with been home. He knocks on her door, she’s not there, he heads over to the ballgame. How much of his story is true?

It’s an extraordinary story. I don’t know. I have been unable to track this woman down. I mean, I know who most of the other women are, obviously not all of them because he was very promiscuous. His first wife can’t figure it out, either.

So she’s thought about it.

Of course. She’s thought about it a lot. I asked her repeatedly. I have her every detail in an attempt to identify her. And then I talked to other girlfriends of his who were around at the time -- one of whom really should have known if there was a way to know. Joyce Harrington died many years ago, so I couldn’t ask her. The problem is it’s so neat. It’s such a neat story. Updike goes to see the woman he’s interested in. He hasn’t yet had an extramarital affair; he’s considering it. He goes to see a woman who lives in the Back Bay of Boston. He’s ready to do it. She’s not there. And instead he goes to see Ted Williams’ last at-bat, and writes one of the great pieces of sports journalism, possibly one of the great pieces of journalism.

Not only that, but there’s the timing of when he told this story, which is a few months before he marries his second wife. Remember, this is Ted Williams’ last at-bat. I think he’s also delivering another swan song. So this is his farewell to adultery. Because as far as I can tell, once John married his second wife, Martha, he stopped fooling around.

So there are two things competing here. There’s Updike’s inveterate habit of using the bricks and mortar of his life in his fiction, and then there’s his inveterate habit of fabulizing. So is he making a neatly rounded story or is he giving us the details? I’m looking forward to reading the biography that’s bound to come out that has every detail nailed down.

Did you assign the famous David Foster Wallace review of “Toward the End of Time”?

I did.

Did you know what was going to happen in that review? That he’d write: “It is, of the total 25 Updike books I’ve read, far and away the worst, a novel so mind-bendingly clunky and self-indulgent that it’s hard to believe the author let it be published in this kind of shape.”

Let’s put it this way. Let’s go back to 1996, ’97. David Foster Wallace is the flavor of the month. He’s just published “Infinite Jest.” John Updike has just published a novel set a couple years in the future, which is somewhat eerily like the future world of “Infinite Jest.”

I looked at this Updike book, and I thought, who’s interested in A) American fiction and B) the near future. I thought, let’s give David Foster Wallace a call. I did not think let’s kill off Updike. When the piece came in and it was supremely negative, I had no more to do with it. Because I was not at the staff of The Observer at the time, I was simply advising them who to assign pieces to. I was nominally the book editor, but I wasn’t in charge of editing. So I assigned it and then it was edited by Peter Kaplan’s widow, Lisa Chase. And Peter obviously conceived of the idea and asked me to execute it -- getting Sven Birkerts to write a companion piece about the senescence of these writers. So yes, I got David Foster Wallace, but no, I was not involved in the attempt to assassinate Updike. I was then an Updike fan. Not an ardent Updike fan. I became more ardent in 2003 when the early stories came out, and then when I began reading him completely and in depth, which in some cases may have turned you off Updike, but in my case, it turned me entirely on. My admiration for him has deepened and clarified.

David Foster Wallace was not a full-blooded critic of Updike. He had in his collection a heavily annotated copy of “Rabbit, Run.” He is an Updike fan. But “Toward the End of Time” is not a good novel.

It’s tough to review these books by great writers at the end of their careers.

It is. David, by the way, was very unhappy about the editing of the piece, and blamed The Observer. Which was one reason I was telling you I didn’t edit it -- the other reason is because it was simply the fact.

Did Updike read this review?

No, the happy thing was that Updike never read this in his lifetime. He read just the beginning of it.

So he knew of it?

He knew of it. Eventually he saw the beginning of the essay, because The Observer ran on its anniversary issue the beginning of it, but not the jump. He wrote me a letter, because I was who he associated The Observer with, and he wrote me a letter thanking me for a review of one of his books, I can’t remember which one it was. Possibly “Seek my Face,” which I’d kind of enjoyed, and written a positive review of. And so he thanked me for that, but in the same issue he noted this article by David Foster Wallace which he’d been unaware of, and he hasn’t seen the jump. Then he said, “The Observer giveth and The Observer taketh away.”

I personally wrote a sharply negative review of one of his books, “Villages,” which appeared in The Observer, and which I have reason to believe Updike disliked intensely. In fact, I never had any contact with him after that review. But I went on to give a favorable review to “The Terrorist.” I mean, to the end of his life he was writing things that I adore. And sadly his posthumous book is very near the top of my list of his best books, “Endpoint,” his collection of poems.

So somebody looking at Updike’s entire career who says, there’s three dozen books, and I don’t know where to dive into this, or what’s worth diving into, what’s simply a prolific writer’s late-career error. Where should people go?

I can tell you where not to go easier than I can tell you where to go, because there’s so much. There’s a tendency to say, okay, I’ll read the Rabbit books and start with “Rabbit, Run.” I think in general that’s a mistake. I love “Rabbit, Run” but it’s a very tough place to begin. Partly because Rabbit is a character that Updike wanted you to sympathize with; he wanted you hooked by Rabbit, and it’s difficult for people in this day and age, especially women, to identify or feel sympathetic toward Rabbit. You can sense that Updike wants you to sympathize and empathize, but there’s very little grounds for doing so. And so I think it turns a lot of people off before they’ve begun. Which is a terrible shame, because if they began for example with “Rabbit Is Rich,” they would be hooked instantly.

And then you can end up with “Rabbit Redux,” which is one of the most powerful and disturbing novels that I’ve ever read. Really, an extraordinary work, and completely different from the other three Rabbit books.

The other suggestion I have for where to begin is a very slight, very sly, very beautiful novel, very short also, called “Of the Farm.” Updike himself had very mixed feelings about it because it was about his mother, and another instance of him writing his life before it happened. He wrote “Of the Farm” in 1965, while he was still married to his first wife, and while his parents were alive and living together. It tells a story of a man going back to visit his widowed mother on a farm that is obviously the farm in Plowville, and he has with him his second wife, and his son. As it happens, when Updike eventually married his second wife, his mother was widowed, and on his second visit to Plowville with his second wife, he brought with him also his new stepson, his youngest stepson. So absolutely recreating “Of the Farm.” It’s an astonishing moment for a biographer’s point of view. But from a reader’s point of view, it’s a gem of a book. Only four voices in it, and absolutely lovely.

You mentioned the way that women respond to Rabbit. Updike receives a lot of criticism from those who see misogyny in his books. Are those critics right?

This is a yes and no answer. There are obviously grounds for charges of misogyny and sexism. There’s a whole slew of female Updike characters who are dumb, or who are silly, or uninformed. He grew as he went along, and as he grew he became more aware of feminine perspectives. He learned to write from a feminine perspective. He learned to make his female characters actors in the world instead of passive sex symbols. If you take a look at Janice in “Rabbit, Run,” and then Janice in “Rabbit Redux,” and then Janice in “Rich,” and so on, until you get to “Rabbit Remembers,” you will probably see the evolution of feminism over four decades.

He was not insensitive to these criticisms. He responded to them as best he could. Not always successfully, because he was, as we discussed earlier, opposed to organized dissent against the powers that be, and the powers that be are of course patriarchal. He would embrace feminist ideas and make fun of feminists at the same time. The case in point of course is “Witches of Eastwick,” where he creates three fabulous, exciting women -- but of course he turns them into witches. And he had the audacity to say they were working women. They were witches. Not a response calculated to endear him to feminists. But the truth is, if you look at that book, it’s a meditation on the nature of female power and it looks at it open-eyed -- and sees that there’s a deficit of female power. It doesn’t celebrate that deficit; on the contrary, it can be said that it laments it.

So what is the legacy? One of the nasty reviews placed him in the second or third tier of American writers. Where does Updike belong as we look back on American letters in the second half of the 20th century?

At the top tier, without question. I mean, making lists of greatest writers is a stupid business. Ranking 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 is stupid. To say that Updike would belong in the top five American men of letters, with “men” in quotation marks… he is one of the top, most important literary figures of the twentieth century, without a doubt.

There’s the undeniable breadth of his work. His poetry, which we haven’t touched on at all. Much better than almost anyone, even his fans, acknowledges. His criticism is first rate and will never go away. His short stories, almost everyone agrees, are among the best written in the second half of the twentieth century. At least six or seven of his novels belong on everyone’s shelf. And that’s a conservative estimate; I could easily make a case for a dozen of his novels.

That’s a huge amount of work that as far as I’m concerned belongs in the front rank. I haven’t in my book made a full-court press case for Updike’s greatness as a writer. My hope was that by reading his life and reading his work along with the life, that would become clear to the reader. I felt that to shout out my growing partisanship as I wrote the book would be an error. And it would just turn people off.

You can’t write 60 books without missing a few times. There are novels that I would not gladly re-read. There are novels I would not recommend anyone to read. But there is not a single novel that does not contain passages of beauty and passages of great interest. There are some books that nobody has paid any attention to for years – “Gertrude and Claudius” is totally charming, very clever. I sadly give it one sentence in the book. But when you’re dealing with 63 books, you can’t deal equally with all of them without trying the patience of your reader.

I re-read everything for this book, and I had read about a quarter of Updike before I started the book. I read the rest, and re-read what I had read before. I was never bored. I don’t think you could say that about any other living writer, any late twentieth century writer, except possibly Raymond Carver because he published so little. Certainly no one who published as fully has the kind of consistency and the kind of excellence Updike achieved.

Would I want to make the case for Updike being a greater writer than Philip Roth? Or a greater writer than Saul Bellow? I bristle at the whole idea. If I was forced to do it, I would say probably that they’re all neck and neck. There are books of Roth’s that I value above much of Updike’s, but neither of them have the breadth in terms of the criticism and the poetry and the mastery of the short story. Roth and Bellow, though they can write essays, and they can write short stories, are essentially novelists.

Updike was a quadruple threat, and there was another threat which no one knows about, and which I’m hoping eventually people will know about, which is his talents as a letter writer. And if and when that book is published, it’s going to be a whole ’nother arrow in Updike’s already crowded quiver.

Shares