Mississippi may soon become the first and only state in the nation without a single abortion provider. The Jackson Women's Health Organization -- the lone clinic left in the state -- has been offering abortion care and reproductive health services to the women of Mississippi for decades, but it's never been easy. The health provider has long been the target of an avalanche of regulations and restrictions passed by a deeply conservative state legislature that has only gotten savvier and in recent years. The latest and most dangerous threat to the clinic couldn't come in a more innocuous package -- a measure requiring the physicians who perform abortions at the facility to obtain admitting privileges at nearby hospitals.

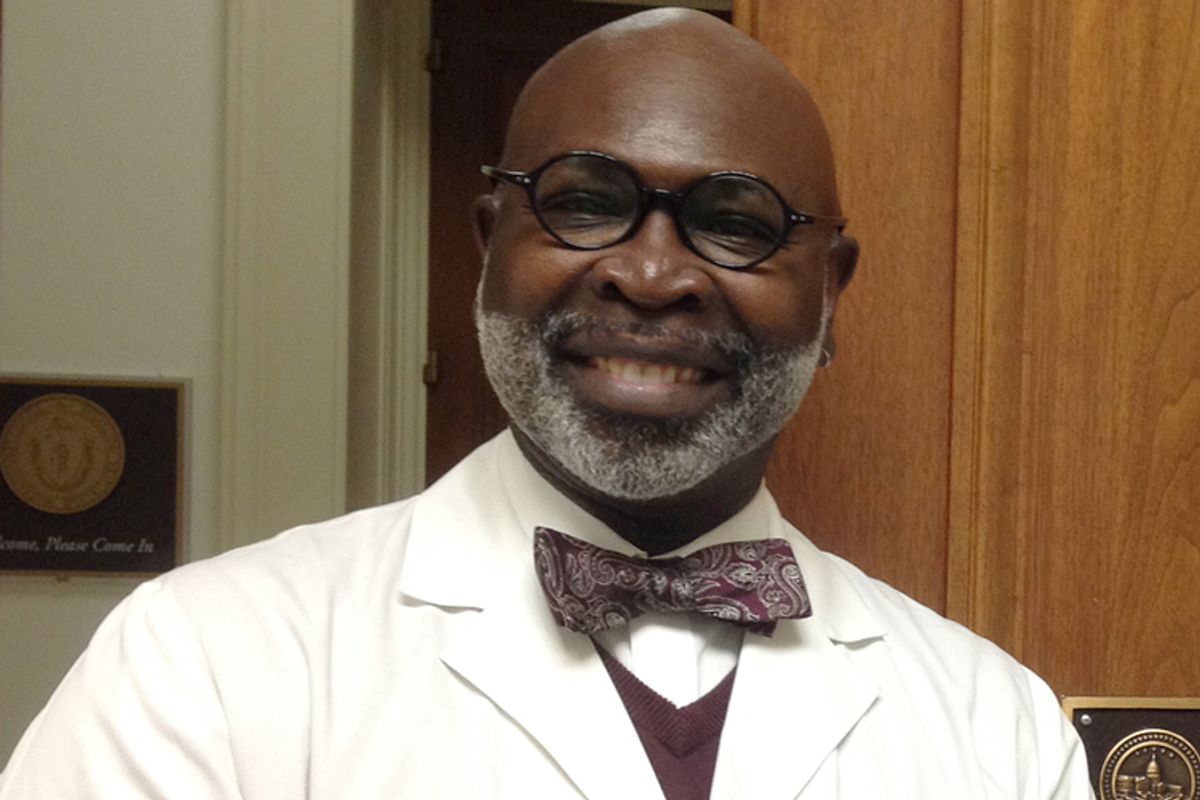

But the clinic has never backed down in the face of a threat, and Jackson Women's Health is staffed by fighters. Dr. Willie Parker is one of them.

Twice a month, Parker leaves his home in Chicago and heads to Mississippi to work at the clinic and ensure women have access to the medical care that they need. When he arrives, protesters are there to greet him. But he endures the harassment, the intimidation and the constant legal threats because there's far too much at stake if the clinic folds. Women's lives are on the line, and he knows it.

Parker is one of the plaintiffs named in the court case challenging the admitting privileges requirement -- a case that will likely decide the fate of legal abortion in the state of Mississippi. He spoke with Salon about the legal challenge and the increasingly bleak reproductive health landscape in Mississippi and elsewhere in the South.

Our conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Mississippi may be on the verge of becoming the first state without a single abortion provider. The Legislature has been targeting your clinic for years, but this admitting privileges requirement is the closest they've come to really ending legal abortion in the state. You're named as a plaintiff in the case trying to keep that from happening. What was the scene in the courtroom this week?

The hearing was an appeal by the state of Mississippi to have the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals set aside the injunction [against the admitting privileges requirement] that the district court had put in place to stop the state from closing our clinic. It was a hearing before a panel of three judges. Our representation, the Center for Reproductive Rights, had their say -- that the district court judge got it right by enjoining this law because there would be irreparable harm to women. The change in regulations would close the only clinic in the state.

My confidence in how this process plays out -- not so much for or against us -- but rather, my confidence in the fact that -- irrespective of who the appointee to the court [is] -- the judges will be ruling on the facts of the case. That it doesn't always work out when you try to guess at the outcome based on whether this is an Obama appointee or a Reagan appointee or a Bush appointee, whether they are a conservative or liberal. The judges made it clear to the state that they are paying close attention to the whole notion of undue burden that was codified in the [Planned Parenthood v.] Casey ruling back in 1992. So the state had the burden of proving why they thought the judge had acted in error in blocking them from implementing the law. The justices heard that and now we're awaiting their decision.

But I felt reassured by the fact that the people who we thought were conservative justices still sounded fully prepared to ask the tough questions of both sides to gain the clarity to rule.

Do you have a timeline on when their decision will come down?

They didn’t give us a timeline. They gave us a 15-minute recess, and we thought a ruling would be imminent. But I think that we reasonably expect within the next few weeks to hear something. And all this really means is that if the justices rule in our favor that the injunction will stay in place, we will stay open, and we will get a trial where we face the merits of our case.

Hopefully we'll prevail there as well.

This is the same court that found the admitting privileges requirement in Texas -- which is remarkably similar to what you have in Mississippi -- did not present an undue burden. In their view in the Texas case, driving hundreds of miles and the other associated burdens created by the new regulations did not prevent women from seeking abortion care. The circumstances are extremely dire in Texas, but Mississippi only has one clinic left. If you close, abortion ceases to be available. Do you think this will influence the judges' view about what constitutes an undue burden?

I think everything hinges on that -- the undue burden. That was the paradigm shift in 1992 with the Casey ruling. After Casey, states were empowered to make rules about abortion that made it, in my opinion, a little less absolute that Roe [v. Wade] protects abortion rights unequivocally. So most of the rules created were based on things like parental notification, spousal notification. But only one of them had to do with health regulations. So this case had to do with health regulations.

I guess the undue burden standard can be looked at cynically -- as it was in the Texas case -- when the presiding judge said Texas is flat and that people can drive 75 miles an hour. So rather than being an undue burden [to have the nearest clinic be hundreds of miles away], it's more of an "inconvenience." I think what makes this difference is that Texas is a big state. And you can drive 200 miles and be in the same state. But Mississippi is not that large of a state. If you drive 170 miles you’ll be in another state, which is around where the closest clinic from Jackson would be.

I think that would be in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. So in this case, I think it really comes down to: Can you impose your duty to take care of your own citizens on another state just because there are services that were formerly available in yours that are no longer available because you changed the rules? Can you do that to your citizens? Can you abdicate your responsibility?

I think it will it hinge on how that’s interpreted.

What do you anticipate happening if this injunction is lifted and the clinic is closed? The stakes here are incredibly high, and I know this is an issue that you have a deep personal investment in. You've dedicated much of your life to ensuring all women -- no matter where they live -- have safe and legal access to abortion care.

It represents the loss of a specific opportunity to provide the care and the service that I feel compelled to do from a compassion standpoint. I do this because it's the right thing to do. To know is to become responsible, and I became aware that women in Mississippi had limited access in this state. It's part of my regional loyalty. I grew up in Alabama, in this neck of the woods in the South. I've lived in places where women are disproportionately affected by a lack of access, and so I felt compelled to move and act. My mom used to say, “You don’t get credit for doing what you ought to do.” So I felt like this is what I ought to do. And while I’m humbled by the fact that people think that it’s some noble behavior on my part, it’s just consistent with my values. It represents, for me, an opportunity to live out and be the person that I think I ought to be.

But -- more globally and more importantly for women -- if this injunction is lifted and the state can proceed to close the clinic, women will be placed in a situation of desperate times that would call for desperate measures. I can’t predict what women would do but I know what is already happening, and the logical conclusion would be that -- as in every place on the planet, both in this country and others before Roe and after Roe -- when women are desperate to not be pregnant they do whatever they need to make that happen.

Before Roe, that meant women taking risks with their health and their lives. And after Roe it will be more of the same. Maybe it won’t be the literal coat hanger, but I have seen do-it-yourself instructions on the Internet about how to terminate a pregnancy. I do know that there are people marketing medicines and drugs to accomplish the same goals. And desperation leads to exploitation. People are recognizing an opportunity to capitalize on the desperation of women. [Drug sellers] will put drugs in concoctions available on the Internet and there will be no way for women to receive instructions around how to use those medications or even a quality assurance around whether or not those medicines actually have the medical ingredients necessary to accomplish the intent. So women will, out of desperation, take desperate measures and they will be victims of people who are looking for a market opportunity to capitalize on their desperation. So it would represent, ironically, the jeopardizing of women's health even though the [admitting privileges] bill purports to improve women's safety by hyper-regulating abortion clinics, and by requiring hospital admitting privileges.

You've now applied to 13 hospitals for admitting privileges in order to comply with the new requirements, but you've been rejected each time. Do you feel these denials are politically motivated?

Well, it’s hard to say. You can speculate about people's intent. But I would say, we first tried to meet the terms of compliance even though we do not believe these regulations are valid. There is nothing about hospital admitting privileges that adds anything to abortion care when we know that less than 1 percent of abortions ever require any interaction at all with hospitals. So while I can't speculate over a hospital's intent, I would say this law is an abuse of regulatory authority. This is the hijacking of the legislative process and the executive function of government leaders in order to carry out specific political ideological agendas.

The fact is that bills changing these medical regulations can be introduced even without consultation with health leadership in the state. Many of these bills have not been vetted by the people who run the department of health because otherwise they would know that -- just from a good health policy and public health practices and epidemiology -- having safe, legal abortions available is good health practice. Rather than speculating about the agenda of the hospitals, I can say that these policies are not informed by the realities of health data and information that would make the policies really related to the improvement of the population’s health.

These regulations are preventing access to an essential health service. These hospitals' rejection of your applications has a profound health impact. They must know that, at the very least.

Well, there is a profound impact. But in fairness to hospitals, most hospitals are proprietary. They comprise their medical staff. Oftentimes, it is not for quality -- it’s for business reasons. So unless a doctor has a glaring record of medical mismanagement and irresponsibility or ethical breaches, there is no reason for hospitals to deny his or her position and admission to their staff.

But when they’re thrust in the middle of something like this -- when states abdicate their regulatory authority by putting hospitals in the position of having to decide who is medically capable of providing abortion care -- I think in a risk-averse manner they see what happens when protestors come. They also are vulnerable to funding mechanisms by the state. So while I think everyone should take courageous stands and do the right thing under every circumstance, I can understand their rationale for shrinking away from the very high-profile position of having to decide whether or not the hospital should grant privileges and thereby circumvent the law that the state intended to use to eradicate abortion access.

I do think there is a responsibility to serve communities and to make sure those businesses have as much integrity as possible, and I think hospitals should be held to that standard. But I also take a more nuanced view of what the role of hospitals are when they are thrust into a position of trying to regulate a service that should be a function of the state.

These new regulations aren't the first the state has used to target the clinic. If you prevail in this legal challenge, do you see this as the end of efforts to close you down, or as just one battle in the war on abortion care?

Well, thank you for that softball. [Laughs] The older people used to say with regards to civil rights -- and I think it’s interesting that the framing of our response is rooted in the civil rights struggle -- but the older people used to say, whether they had a victory or a defeat in the quest for civil rights: “In times like these there's always been times like these.”

As you rightly note, since the clinic opened almost 30 years ago there has been no shortage of policy -- targeted regulations aimed at making it difficult, if not outright impossible to keep the clinic open. So in that context, “In times like these there's always been times like these.” This is just our battle today. I think there will always be a battle for human rights. Fredrick Douglas said it best: "Power concedes nothing without demand.” He said that the battles will always be moral, physical or both, but it will be a battle. So I think that’s my framework -- why I’m doing this work.

I did feel reassured by the courtroom process, but it's just one battle. It’s not the whole war. So we just have to show up and do the right thing because it's the right thing to do. And we hope, as Dr. King said, that the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice. Sometimes we’re not as far along that arc as we’d like to be, but we have the confidence that that’s where we’re going.

Shares